How Biometric Software is Changing How We Understand Architecture—and Ourselves

It doesn’t matter where they are—city, state, country, continent, it makes no difference. When it comes to big and boxy glass buildings, the human brain is hardwired to take them in the same way: as not much. Here are photos of towers in New York City, Boston, and Toronto. Below are the heatmaps, generated by biometric software, predicting where people will look at first glance, or within the first few seconds, before their conscious awareness is activated.

The heatmaps glow red where people might look most, fading to blue and then black in the areas that are ignored. What’s stunning about the images is how much of the buildings is initially not considered; our brain focuses on the edges, areas of high contrast, and ignores the buildings’ core. Wherever we may encounter massive, glassy boxes, we process them in the same way.

The same is true with blank walls; human instinct is not to look at them. These findings can help explain an interesting phenomenon, why wall art helps revitalize blighted urban areas, as seen in these pictures from downtown Cincinnati:

Note how attention shifts to engage with the wall once it has colorful art, rather than focusing on its edges and the parked auto when the wall is blank. At the far right, top level, regions of interest (ROI) diagrams indicate with red contours that 88%–96 % of predicted views will fall in the center of the building’s new mural, the area that is most ignored when the wall is blank.

Welcome to our New Age of Biology, as the OECD, or Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, labeled the 21st century in 2012, where new insights in life sciences, paired with new technologies, have transformed not only what we do, but how we see ourselves and reframe understandings of what we need to see and be around to be at our best.

The tech tool here is 3M’s Visual Attention Software (VAS), which arrived in 2011 and became a plug-in for Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator in 2020. (There are similar biometric tools on the market now, including attentioninsight.com.) VAS developed from over 30 years research at 3M, studying human responses to visual stimuli. The software simulates the first, subliminal phase of vision, which is before gender, age, or culture affects our attention, and also before conscious awareness sets in. Initially used to inform the advertising, website, and signage design, VAS is now working its way into urban planning and architectural research and curricula. 3M promotes it as a “spellcheck” for all types of design, since, after all, the human viewer and the biology of our visual perception remain the same.

“The students are very excited by this software,” says Catholic University of America architecture professor Robin Puttock, RA. Her students used VAS for the first time to analyze new construction on their Washington, D.C., campus this spring. “I see so many ‘a-ha’ moments on their faces when they understand what it does and what it can do. They want to run photos of their latest design boards to learn what people will see first, and start brainstorming other ways they can use it.”

VAS made her and students see buildings differently, she said. “It has been interesting to note time and time again in our research that simple glass facades are just not seen by us precognitively. Humans seek visual interest, patterns, edges, nature and most of all, other humans. This has made me think more critically about what kind of buildings support our well-being.”

When it comes to understanding how ornament and detail, as well as organized complexity, matter in building facades, VAS can make the case quickly. For instance, because humans are hardwired to ignore blank spaces, the brain directs a viewer to look around Cincinnati’s modern art museum, the Contemporary Arts Center, by Zaha Hadid (completed in 2003), rather than at it. Note how, in the images below, the VAS Visual Sequence diagram goes around the new building, while staying in the center of neighboring 19th-century building facades, shown above it. No surprise: A decade after opening, Metrobot, a sculpture in the museum’s collection by Nam June Paik, was installed permanently outside the museum’s front door in 2014. And VAS’s Visual Sequence suggests how the sculpture is, actually, truly magnetic, making the museum door easier to find.

Ironically, high-tech tools like VAS allow us to confront something designers often neglect: consideration of our animal nature and how evolution, and the struggle for survival that made us, preset human visual biases. The fact is, these visual proclivities all remain ancient, making us Stone Age creatures, not modern at all. It’s something we may struggle to accept, but something we should understand: how buildings impact our behavior, our stress levels, and, ultimately, our overall health.

“Our visual system very rapidly computes edges, brightness, local intensity contrast and color contrast, as well as the presence of facelike geometries,” says Alexandros Lavdas, a neuroscientist using this biometric tool to research the built environment. “This rapid computation has a survival value, as it allows for quick reactions to be initiated, even before the nature of the stimulus has been consciously understood.” Evolving in the wild, we essentially still remain wired for that ancestral place.

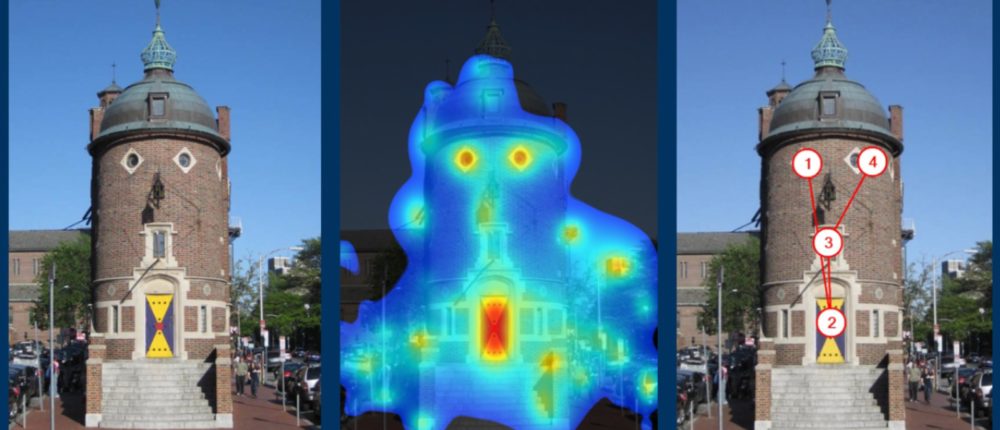

Why does embracing our animal nature and using biometric tools to track it matter in architecture? “Because it gives objective data on issues that were considered subjective,” Lavdas says. Biometrics like VAS “provide an evidence-based tool, and it makes it more difficult to defend forms that do not visually engage the viewer.” And with powerful data points on how engagement actually happens, we can better explain human behavior in all kinds of built environments, such as why a facelike façade in the Harvard Lampoon building in Cambridge, Massachussets, is so often photographed and a frequent stop for tour groups.

Of course the travel buses stop here; they have to. The tower grabs people subliminally, anchoring them in the space and making it memorable. Exactly the opposite experience people have with the glass towers, as seen above. And it doesn’t matter that this brick tower is over a century old—it will have the same affect on people a century from now. The fact is, our perceptual system, unchanged for some 40,000 years, will remain essentially the same for a long time.

And that may be the surprising take-away from this biometric tool and architectural research: Helping people understand they are not as different as they think. Asked how VAS changed her perspective, Puttock said: “I find it fascinating that we are all essentially the same. We see the same things precognitively based on our shared evolution.”And what could be a more fitting finding for the start of the 21st century than the Age of Biology? Understanding how we look at buildings helps us to see ourselves.

All images courtesy of Ann Sussman.