Great Teachers of Architecture and Design Teach the Art of Looking

We learn, most of us, from words and numbers on a page or on a screen. Once this meant a physical book. Now it can mean various forms of interactions with computers.

But deep learning involves the personal touch. I’m often startled to see how often great professors were in turn the students, close ones, of other great professors. It’s almost the laying on of hands, like gurus or yogis, the passing on of some sort of knowledge that can’t be communicated by a book, no matter how well written.

Something like that happened with me during my brief time with Professor Eduard F. Sekler, who passed away earlier this month at the age of 96. In the spring of 2000, I took a small seminar course, The Shaping and Preservation of Urban Spaces, while a Loeb Fellow at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Sekler was about 80 then, an emeritus professor, but still teaching, spry and full of life. About eight to ten of us would gather around a table once a week, in the Carpenter Center (the only building designed by the famous Le Corbusier in the United States). In the 1960s Sekler had been the first director of the Carpenter Center, while he was also co-founding the school’s department of Visual and Environmental Studies, so he was at home there.

Almost two decades later I can describe what took place during those weekly gatherings, but saying why it influenced me so much is harder.

The other students were mostly Europeans, and most were graduate students in architecture or some other field of design or planning. Sekler would show slides, and then we would discuss them. We had to write various papers, including one where we went out and selected a historic urban space, traced its history, and then came up with recommendations for it. We did three amazing classes on Venice, and he transferred a love and respect for the ancient empire that I still carry with me. We looked at the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, where Sekler had worked with UNESCO to preserve the monuments and buildings there.

The impact of his class came more from discussions, and what Sekler said and showed. He gave me question I still ask, rather than answers. He spent one class talking about how people see, and what happens when you set something apart.

But the impact of the class came more from the discussions, and what Sekler said and showed. He gave me questions I still ask, rather than answers. He spent one class talking about how people see, and what happens when you set something apart. He took something ordinary, perhaps a rock, and then put it in a frame, and then focused a light on it. He then asked us to think about the changes that happen in our perception when this occurs, and the choices involved. This sparked my thinking, because I saw it as applying to my own profession, journalism, which I saw at once, is all about selectively taking some things and putting lights on them, while ignoring others.

Another class he spent time talking about optics. In the 16th and 17th century, philosophers and scientists (they were the same thing then) got incredibly engaged in trying to figure out how the human eye worked. How did it process light? Sekler dug out the original writings on this, and had us look at them. I didn’t understand it all, and still don’t, but the questions still intrigue me.

Another moment that sticks in my mind is when for some reason, maybe during a break, Sekler and the largely European students discussed the difference between Americans and Europeans. They agreed that the U.S. was a better place to be professionally, because Americans were more open to new ideas, new people, less threatened by them. At the same time, they also agreed that Americans were more self-centered, less appreciative of life.

Sekler told the story of walking a street in an Italian city, and seeing a woman vigorously scrub and polish a wooden table. Then she stood back, and said: “Ah, it shines like the sun!”

An American, Sekler said, would probably have worked grumpily, complaining “why do I have to do something like this?” The story sticks with me.

He was kind, always available with his time. A native of Vienna, he had been hired to the Harvard Faculty in 1955 by the Spanish architect Josep Lluís Sert, the influential and longtime dean of the GSD. This was an interesting connection and disconcerting, because Sert helped screw up Cambridge in the 1950s and 1960s by leading the charge to bore in urban-renewal style boulevards and tunnels, in line with the modernist logic of separating cars and other uses. At the same time, I have read some of Sert’s writing, and they are very perceptive. I never got the chance to hash this out with Sekler.

I did give Sekler a draft of my first book, How Cities Work, which was then in the copy editing phase. He read it, and made notes and suggestions, which I followed.

After I left Harvard and moved to New York City, I kept in touch a bit but not as much as I now wish I had. It was partly the opposite of false modesty. My respect for the professor was so great, I thought he wouldn’t want to talk to me. A dumb notion.

I did consider writing an article directly about one aspect of his class. Every year, for decades, Sekler had asked students to list what books they most admired and were most influenced by. He did it with us. And then he kept lists of those lists.

What he had noticed over the decades he taught was the ascendence of Jane Jacobs and urbanism. In the early decades, probably the 1960s and 1970s, work by architects were at the top of the list, he said. But at some point the slow and steady rise of Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, began. It still topped the lists when I was there. And these were books named by mostly architecture students, mind you, not urban planners. I envisioned an article that would show samples of these lists from year to year, and how they changed.

While I now wish I had gotten around to that, I won’t regret it too much, because one can’t do everything. Better to savor having known the professor, and getting the chance to take his class. He communicated to me something about appreciating, something about thinking and seeing, that’s hard to put into words, but which I know is there.

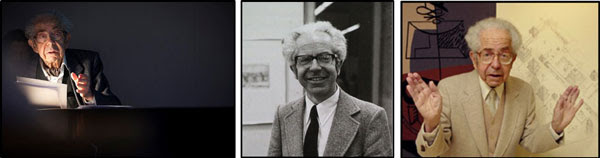

Featured images of Professor Sekler courtesy of the Harvard Graduate School of Design.