Modern Restoration and the Veneration of Its Hero Architects

Billions of dollars are in the process of being spent on the restoration of buildings just two or three generations old: Mid-Century High Modern Architecture, work designed by the profession’s 20th century pantheon of heroes—Marcel Breuer, Louis Kahn, Le Corbusier, Eero Saarinen, Paul Rudolph and their contemporaries. This effort involves more than technical corrections and repairs. These buildings are what’s left of the modern movement’s founding fathers; like any triumphant movement veneration increases with the passage of time. The conflation of the designer and the design means each structure becomes a personal embodiment of architects who become more heroic with each passing year.

But modernist buildings have a strong legacy that is not historic. Its generating design principles were more than aesthetic. The genesis of modern architecture is woven into the early 20th century’s rejection of the old world, as the Industrial Revolution changed western civilization forever. Science trumped religion, technology overwhelmed tradition, and The New was a priori superior to the Old. To restore a modernist building is to capture the spirit of the designer, not history.

Accordingly, the costs of perfect fealty to the design intent of art are extreme, as renewed newness in an aging building takes extreme care, since all of the updates must be invisible upon completion. This is not renovation: it’s work of religious purification and fine arts conservation. But the majority of these restorations are not museums; the revived buildings usually maintain their intended use, and their revivification is done with a zeal and fervor previously reserved for antiques.

In religion, the most holy keepers of the faith are made saints. In architecture we tend to sanctify buildings. In the 21st century, the style of building that is most devoutly venerated by most architects, architecture schools and critics is the work of greatest generation Modernist designers. Restoration of these signature buildings means that huge effort is made to render them in full seamless denial of the new technologies underneath their skins.

Whether high irony or disingenuous hypocrisy, the results are often astonishingly perfect, and that’s the point. Make no mistake, the last visible layer masking the improvements and repairs to the host building are an extreme conservation effort—more akin to fine art than architecture—like revealing the lost genius of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling.

We’re used to patina and provenance in traditional buildings. A little soot here, moss there, maybe a crack or two, makes vernacular buildings age into their contexts. For most of us, aging is a natural process, too. Gray or less hair, wrinkles, sag and stoop attend the gravitas of time. But modernist buildings are like fashion models: intolerant of visual evolution. When the gist of a design ethic is surfing a wave of innovation, the aging of innovation becomes oxymoronic at best, and often embarrassing.

Rather than tolerate the evolution of modern masterpieces into a different reality like so many gothic churches becoming coffee houses, great modern architecture seems to demand absolute recreation of its edgy newness. It’s cosmetic plastic surgery for middle aged buildings.

The call to modernist restoration is not just about technological updates, repair of failing surfaces, or structural miscalculations. It’s about belief in the embodied magic of the genius architect and faithfully channeling the designer’s posthumous input. No one wore WWKD (“What Would Kahn Do?”) bracelets during the exquisite restoration of Yale’s Center for British Art, but the journalistic love that project architect George Knight has received is based on his unconditional devotion to the master. “It’s sort of a whisper that you hear,” Mr. Knight said in the New York Times. “There’s a phenomenal understated quality to this building. It’s always” — he drops his voice — “Are you sure you want to do that?”

This channeling aspect was once reserved for restorations of buildings hundreds of years into history. Beyond following the drawings and construction photos that comprehensively document the literal nuts and bolts of 20th century construction, today’s projects go beyond the conventional rules of traditional preservation architecture. There is no stylistic history to adapt; only the mind of the original designer to commune with. The cult of personality so necessary for the modern movement’s success is now being frozen in perfectly restored embodiments of genius: the movement’s built product.

There may be more High Modern Buildings per capita in my little hometown of New Haven, Connecticut that in any city in the world. The New Haven Preservation Trust lists more than 100 mid century modern structures on its website. This small city of less than 120,000 residents may be the epicenter for modernist restoration: hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested over the last decade to stabilize and purify iconically modern buildings.

In addition to the aforementioned Yale Center for British Art, Kevin Roche’s Knights of Columbus Tower had a complete reglazing and a new HVAC system installed without benefit of the original architect. Eero Saarinen’s Ingalls Rink (affectionately dubbed “the Yale Whale”) buried new locker rooms and training facilities to make them visually disappear. A new building, the 87,000-square-foot Loria Center, designed by Gwathmey Siegel, was grafted onto Paul Rudolph’s original 114,000-square-foot Art & Architecture Building, to allow the host building to be completely returned to its perfected 1963 state (and now heroically re-named Rudolph Hall.)

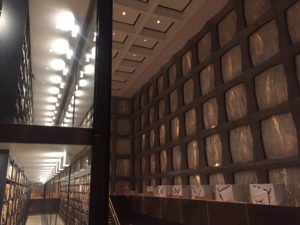

But Yale’s latest effort, a $70 million restoration of Gordon Bunshaft’s Beinecke Library is an exceptional example of hiding new technologies under rewoven modern fabric. In full “don’t ask, don’t tell” obscurity, miles and miles of data-pushing cables are now coursing around and through the library, completely unseen in an architectural persona that was originally based on the proud expression of new technologies. Even in the era of green guilt, the one-inch marble skin remains completely uninsulated, but cleaned and stabilized and restored to visual perfection. The restoration of this now iconic building compliments its added status as the unintentional Memorial to the Dearly Departed Printed Word.

Time seems compressed in the 21st century. Technology creates instant, universal newness at the drop of a Pokemon. But buildings are time travelers—they should last. When boomers replace a knee, get a Botox injection or just take up yoga after 50, they’re hedging their bets, hoping to break the rules of inevitable decline. It’s even harder to simulate the blush of youth in buildings, especially buildings designed to express the zeitgeist of 60 year old innovation.

We can beat against the tide, but it goes out, despite billions of dollars and the desperations of mortality.

Featured image: Ingalls Rink, courtesy of Yale University.