A Radical (and Totally Practical) Rethinking of U.S. Housing Construction

What if the housing crisis wasn’t about the cost of lumber, labor, or land, but about bureaucracy? Imagine a world where, instead of developers navigating an obstacle course of entitlements, permits, and approvals, cities themselves took on the challenge of creating the housing they want and need. The good news: there are two models that show how U.S. cities can fast-track high-quality housing that people want to live in and enjoy seeing on the streetscape. The first is Vienna, a global model for affordable housing that shows how streamlined processes and collaborative policies can rapidly deliver high-quality, affordable urban homes. The second is Paris, where in the mid-19th century the city created a set of standard architectural plans, enabling the efficient, large-scale construction of now-iconic neighborhoods, reproducing a model that goes back to ancient Rome.

By combining Vienna’s modern approach to planning with Paris’ historic model, U.S. cities can:

- Accelerate housing development by streamlining entitlement, permitting, and approval processes.

- Prioritize affordability by implementing policies that directly support affordable housing.

- Foster sustainable design by encouraging innovative, eco-friendly building practices.

- Design and create vibrant neighborhoods with walkable, mixed-use communities.

- Control quality by creating standard plans for infill development that lock in high-quality unit layout and sustainability.

The Problem

Research from the Terner Center at Berkeley, as well as data from projects in California, reveal how red tape, delays, regulations, and fees can as much as triple the cost of housing—costs unrelated to materials, labor, or land. This results from an adversarial and time-consuming entitlement and permitting process, which can result in expensive, low-quality housing that is out of proportion with the street and has high-carbon footprints that lock in car culture. The knot of regulation has stifled small apartments, starter homes, townhomes, and other naturally affordable housing options, even in thriving housing markets like Los Angeles and San Francisco. It simply stopped penciling out to build missing-middle, affordable, and workforce housing. As a result, housing shortages have driven prices skyward, making it increasingly difficult for the average Californian to afford a home.

How did it come to this? The regulations are a result of stakeholder (i.e., NIMBY) objections to new development, leading cities to create a lengthy process of red tape and delays. Cities also added rules, requirements, and fees (“extractions”) that should benefit the community in return for being allowed to build. Some cynical municipalities, however, designed the system to purposely undermine the finances of housing. These municipalities can make a show of allowing very few units through the system, while intentionally tying housing up in knots so that nothing pencils out—and what doesn’t pencil, doesn’t get built, which is the real goal.

Proposed Solution

What if, instead of asking parcel owners, builders, and developers to navigate an expensive, time-consuming permitting process to build the housing a city needs and wants, cities took on much of this responsibility? Vienna and Paris offer proven models for streamlining red tape and creating high-quality housing that stakeholders embrace. Vienna has been so successful that renting or owning there is half the price of London housing, and one-quarter that of New York City. Paris built housing of such high quality that it is still sought after, 170 years later.

The Viennese Model

Vienna created a process in which the entitlement and permitting process is flipped, and while it doesn’t exactly translate, it can be adapted to U.S. cities. In essence, for much of Vienna’s housing, the city decides where it wants new homes and what they should look like, and then it fully entitles and permits projects, allowing builders to focus on what they do best: construction.

Here is how it works: Vienna sets development goals and ensures that land is appropriately zoned. Then it organizes design competitions and invites entries that align with the rules and goals. A jury of experts and local stakeholders choose a winning design, and the city accelerates the project and issues the equivalent of a ready-to-issue permit. The city also provides essential infrastructure (roads, sewers, etc.) to reduce the burden on developers. Developers and builders are then able to focus on high-quality construction.

The outcome? Construction costs in Vienna are half those in the U.S., despite higher labor costs. It’s not due to cheaper materials, either; construction products are sourced from the international market, and Vienna often uses higher-quality, more expensive materials compared to those commonly used in the U.S. At its core, Vienna plans for the housing it wants, and then makes it easy to build those projects. U.S. cities can adapt this model at a large scale by marrying it with the Paris standard plan model.

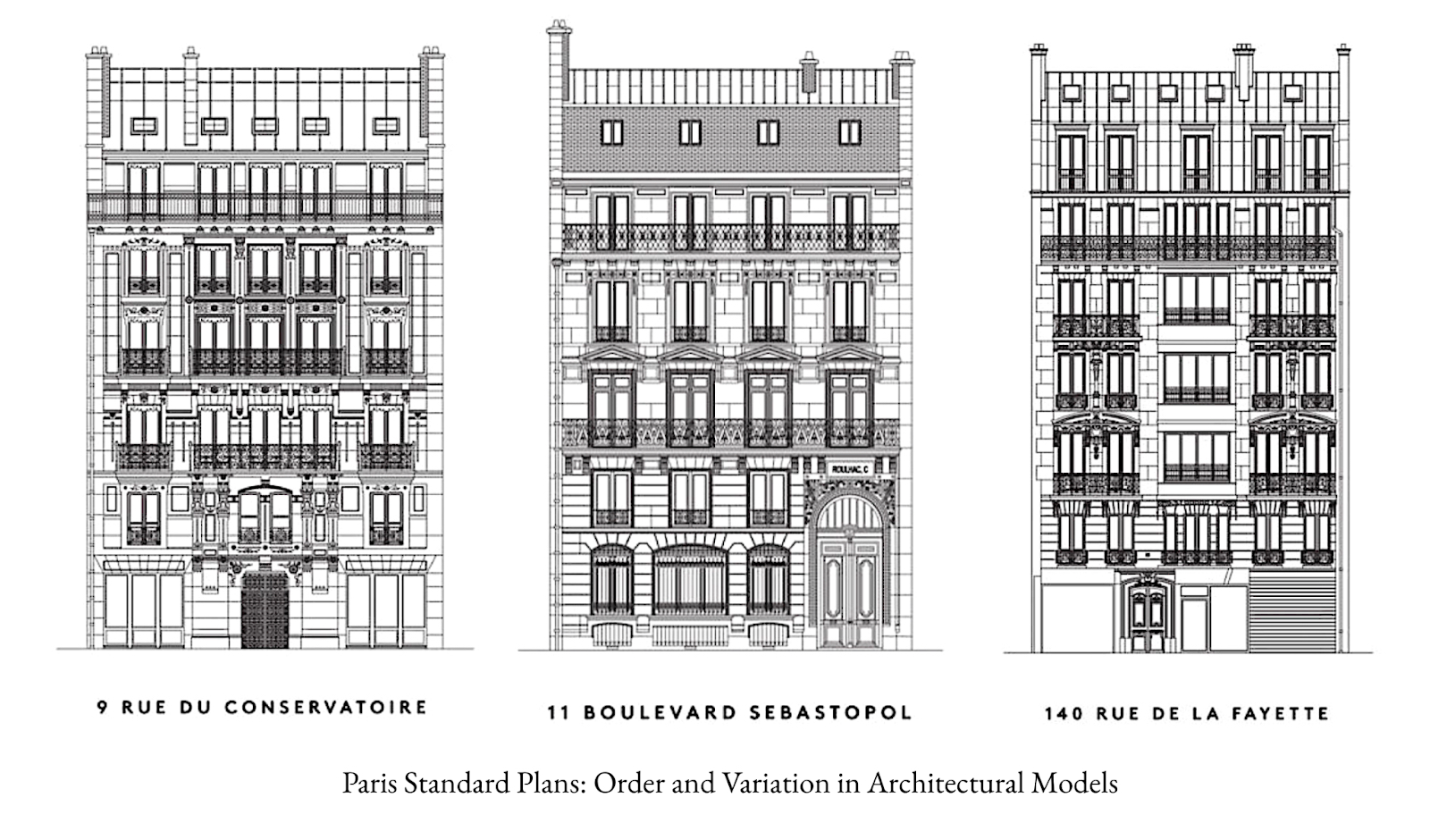

Paris’ Standard Plans

In the late 1800s, Paris proactively planned the city and developed architectural plans that were essentially the same structure—the iconic Paris building known the world over—with variations on a theme: six stories (typically), clad in limestone, featuring a pattern book’s worth of decorative elements. These plans were given to builders fully entitled and permitted; free to build, they created some of the world’s most admired streetscapes. There are other famous examples of standardization across the globe as well: Brooklyn brownstones, London townhomes, Savannah row houses.

At times these buildings have been written off as monotonous, but they are now some of the most sought-after residential neighborhoods around the globe. Humans are naturally drawn to streetscapes that have a consistent height, provide a human scale, and balance order with variety. This combination fosters a sense of calm amid the bustle of urban life, enhances curb appeal, and safeguards the long-term investment of first-time and low-income homebuyers. The appeal is clearly demonstrated by the high real estate values of these developments. Ultimately, the question is simple: Where would we choose to live?

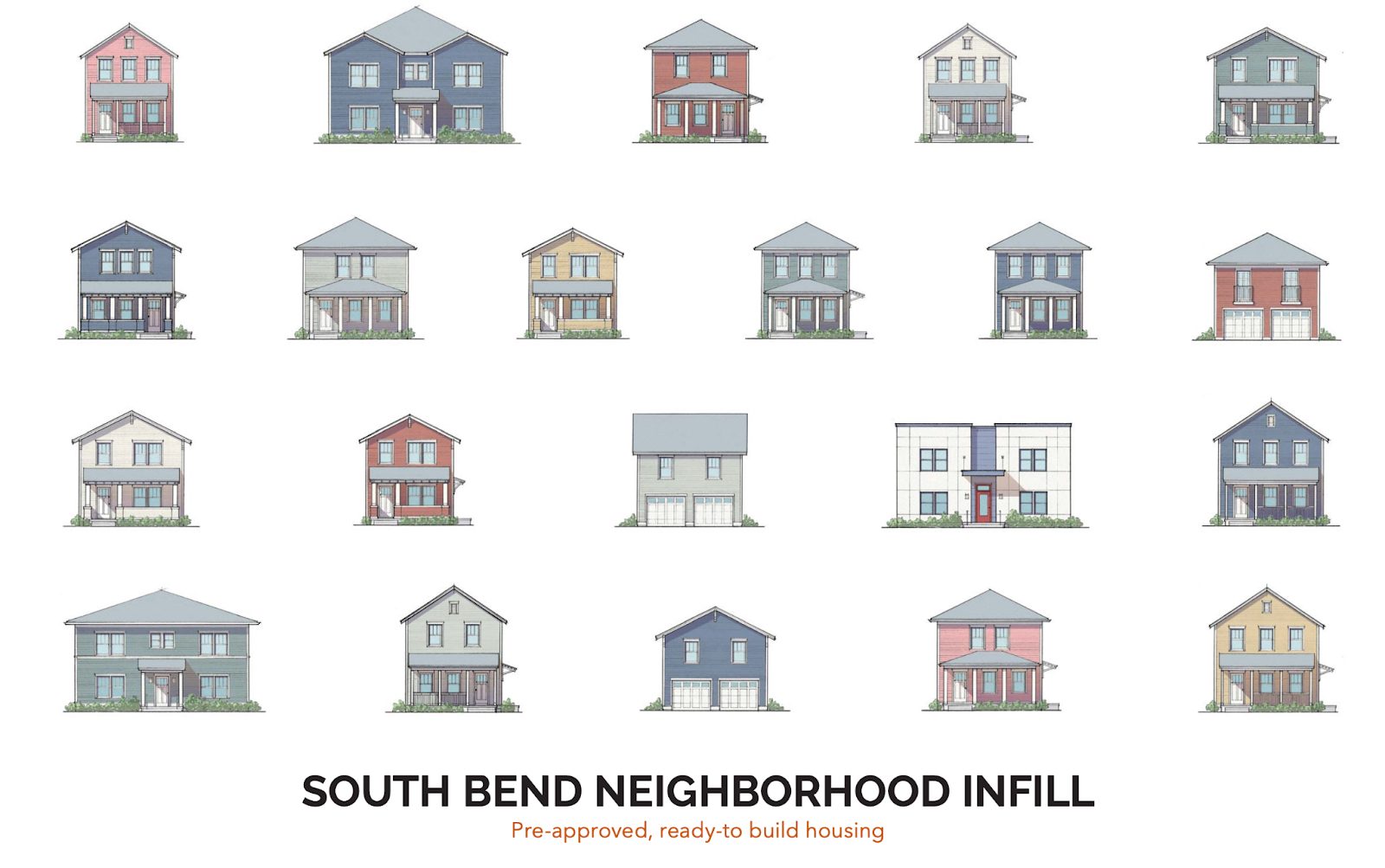

Standard plans are becoming a favorite tool for streamlining development in cities across California and elsewhere in the U.S. By pre-entitling plans for ADUs and small multifamily buildings, city governments fast-track the process, reduce costs, and make the design and permitting process easier on small builders and property owners. The idea is to get existing parcel owners to develop housing themselves. “Since the ADU reform agenda took hold in Sacramento in 2016, the number of ADUs permitted each year in California increased by 15,334% – resulting in 83,865 permitted ADUs statewide,” according to California YIMBY, a statewide advocacy organization.

This idea of standard plans can be extended to create urban infill projects. On a commercial block, parcels are the same size by design, and the majority come in a few standard sizes: 40 or 50 by 100, 140, or 150; 25 or 30 by 90 or 100. A neighborhood can use a design competition or a submission process to choose favored architectural plans and pre-entitle them for every parcel on the street. The city can then collaborate with the builders to fast-track permits and inspections, thus reducing construction delays.

Paris and Vienna Also Solve Mobility

Permitting has been a key factor in Vienna’s and Paris’ success in creating high-quality urban environments, but it’s not the only factor. In Vienna, all daily needs are within walking distance, a concept later popularized as the “15-minute city.” This approach is essential to building cities where people genuinely want to live.

Both cities feature vibrant streets that make walking and shopping enjoyable. Vienna boasts a fully pedestrianized city center and one of the world’s best bus and tram systems. This first-rate mobility system eliminates the need for cars and therefore the need for costly on-site residential parking. This further reduces construction costs, which in turn lowers housing prices.

Five Key Steps

U.S. cities can adapt the Vienna and Paris models to streamline high-quality housing through five key steps:

- Inventory available land in walkable neighborhoods: Identify underdeveloped commercial corridors with fine-grain neighborhoods serving retail near jobs and transit. Small retail shops offer convenient access to all of a person’s daily and weekly needs, creating the bones for a 15-minute neighborhood. Cities can create an expedited process like the one developed by the Livable Communities Initiative to build housing above that. Another priority is to choose corridors that are near high-quality public amenities (parks, schools, etc.) and located in high-opportunity neighborhoods to align with AFFH (Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing).

- Choose the architecture: Create a panel of stakeholders and experts to select high-quality designs that align with the neighborhood’s aesthetics through a design competition or a submission process. The process can allow for multiple routes; for example, when a great building is built, the architect and neighborhood can petition the city to have it become a standard plan, so any parcel owner can erect the same building (perhaps with slight variations).

- Create a Department of Streamlining: The next step is to pre-entitle these designs and fast-track them so projects can be permitted to break ground in 60 to 90 days. This is standard across the world and in many states. There’s already an example of this in L.A.: The mayor’s office created an extraordinarily successful model for fast-tracking and streamlining permitting for construction that was used to quickly build schools for the Los Angeles Unified School District. Created by a former L.A. city planner, Jane Blumenfeld, the program established a specialized department inside the mayor’s office focused exclusively on efficiency, speed, and cost reduction for the schools project. Such a department can be recreated for housing. Using the same model, it would address permitting holistically and coordinating with all necessary agencies (e.g., water, power, fire, urban forestry). Its mission: Make housing feasible by supporting development, not obstructing it. This is a paradigm shift: the city plans where it wants housing and what it wants it to look like (high-quality, zero-carbon, family-sized starter homes in walkable neighborhoods near jobs and transit, etc.). Since the city wants this housing, it’s the job of the departments to make it easy and feasible. In the U.S., this approach could allow a five-story building to be constructed in under six months. Why should a city make it easy on developers? Housing is what the city needs and wants. By creating a process that’s efficient, simple and pencils out, the city aims to persuade owners in designated areas to develop their own land, adding buildings that the city and community desire.

- Implement local street improvements for the higher-density neighborhoods: To foster diverse, thriving livable communities, residential development must be located away from heavily trafficked roads that are noisy, dangerous, and polluted. Cities can implement traffic-calming strategies or, even better, transform these streets into car-light or even partially/fully car-free zones. By providing residents with alternative transportation options like safe bike paths, accessible transit stations, and shared car services, cities can create a more sustainable, equitable, and enjoyable urban living experience. These mobility improvements, combined with enhanced streetscapes and an abundance of high-quality affordable housing, can revitalize neighborhoods and attract a wide range of residents.

- Include public benefits like affordability, sustainability and economic development: The goal of streamlining is to reduce nonessential costs and increase feasibility to incentivize and catalyze housing construction. An added benefit is that there is then more room for public benefits such as sustainability, affordability, high-quality design and construction, and high-quality union labor. Given the climate emergency, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to reduce driving and thus vehicle emissions, as well as residential emissions. (Ideally, all of California’s needed 3.5 million homes would be zero-carbon buildings offering zero-carbon mobility.)

Here are existing ideas and programs that deliver substantial public benefits while protecting the feasibility of projects. These can include requiring:

- Zero-carbon buildings.

- Ground-floor neighborhood-serving retail to promote walkability and convenient, car-free living.

- Locations near jobs and high-quality transit.

- Affordable starter homes and clear pathways to homeownership.

- Homes across a range of sizes to accommodate different levels of affordability.

- Locating development so it aligns with AFFH.

- Facilitation and opting into low-interest loans for low-income first-time homebuyers.

- Granting priority to support local goals; existing programs include teachers/school employees, public-sector employees, local employees, essential workers, low-income households, people with disabilities, seniors, and so on.

Outcomes

If the public benefits were combined, these could help cities and the state meet numerous goals: lower carbon emissions, fewer vehicles on the road, more affordable housing, equity and economic diversity, homeownership rates, recruiting and retaining teachers, ADA, economic development, jobs, small business creation, crime reduction through vibrant streets, and recruiting and supporting public sector employees.

While this program can unlock starter homes in cohesive 15-minute neighborhoods, it’s also designed to catalyze a local building industry of small builders, engineers, and architects to address the latent demand for starter homes in the $500,000-$650,000 range to address CA’s deficit of 3.5 million homes — which has the potential to unlock over one trillion dollars in economic activity. Low-cost financing and a variety of small builders can create innovation and competition for quality and price, with quality going up and construction prices coming down, so more housing is built (which will reduce overall rents). Innovations could include unlocking prefab and factory-built components to further reduce costs. These innovations can help subsidized affordable housing developers by creating a faster, more cost-effective way to build high-quality homes at the speed and scale our country needs.

To support these efforts, municipalities can approach this program as economic development, and consider reviving a redevelopment agency (RDA) model or tax-increment financing (TIF) model for financing infrastructure improvements, street improvements, planning department staff, and reducing or waiving fees.

The housing crisis in the U.S. is at a crossroads, especially in California, as the state struggles to build housing—especially high-quality starter homes—and to meet climate goals. By adopting Vienna’s proactive, streamlined model and Paris’ standard plans model, cities can create neighborhoods that are affordable, beautiful, and functional. It’s a simple idea that is not as radical as it sounds: To plan our cities for high-quality housing, safe streets, and healthy and inviting neighborhoods—and then execute at the highest level.

This essay is part of the Livable Communities Initiative, an L.A.-based nonprofit amplifying the best research to create 15-minute neighborhoods with a holistic approach to housing, traffic, and mobility.

Featured image: Washington Square West, Philadelphia, via Flickr.