Courtyard Urbanism: What’s Missing From American Cities

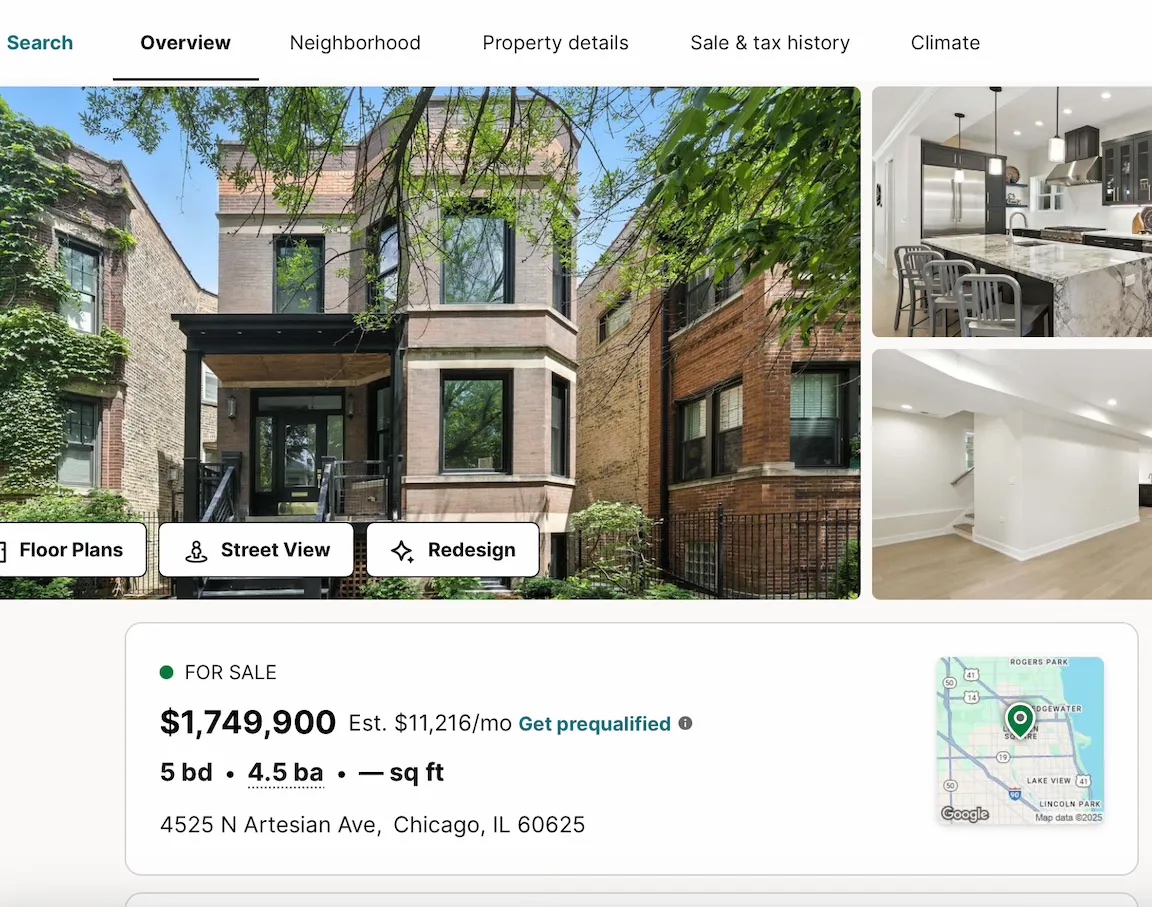

Around 2022–2023, I became increasingly aware of the real estate pressures that were driving families out of the city and into the suburbs, and of the urban planning and architecture norms that exacerbated these real estate pressures. At that time, I was a stay-at-home mom raising three young children and a dog in Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood, where my husband Pete and I had purchased a home in 2017. As our kids reached elementary school age, I watched many families move to the suburbs because they could not afford to stay in our neighborhood, where housing stock is limited to small, yardless apartments and unattainably expensive single-family homes. At neighborhood playgrounds, chatting with parents as our kids played, I heard countless iterations of the same story: they loved the neighborhood and wanted to stay in the city, but they’d outgrown their two-bedroom condo and were moving the suburbs because they could not afford the down payment for a $1 million-plus single-family home. The families who stay in the city tend to be very small or very fortunate.

The urban family exodus bothered me because I had observed, while living and traveling in Europe in my 20s, that many European families raise children in spacious apartments with shared courtyards in the city centers. These urban family homes, I soon learned, were made possible by the perimeter block (aka courtyard block)—a building form common in European cities but rare in the U.S. Each block is enclosed by 10 to 20 apartment buildings, typically four to six stories tall, built wall to wall to form a continuous perimeter around a central courtyard. Because the buildings are wide yet shallow, each unit usually has a front façade facing the public street and a rear façade opening onto the private courtyard. In this way, European courtyard blocks offer the functional equivalent of a “big house with a yard” while preserving the density and mixed-use character essential for walkable, affordable urban neighborhoods. Comparing this model with the “freestanding” structure of American city blocks, I came to believe that American urban design—shaped by zoning laws, building codes, and architectural conventions—effectively prevents the kind of family-friendly density that supports successful cities.

Realizing that very few people were writing about this topic, I began publishing opinion pieces in 2024 for the Chicago Tribune and other outlets, while also posting regularly on Substack. I initially focused on local concerns, making the case that Euro-style courtyard blocks offer a compelling solution to Chicago’s family flight problem. As my social media presence grew, reaching 10,000 followers in just 14 months, the scope of my work expanded. I now argue more broadly that building courtyard block housing can help America’s depopulated cities attract suburban families, with far-reaching benefits for urban life, family wellbeing, and the cultural and civic fabric of the country.

While writing about courtyard urbanism has been extremely entertaining, I’ve learned even more by engaging directly with my city and neighborhood. Through local urbanist groups, serving on the board of my neighborhood organization, and collaborating with elected officials and developers, I’ve worked to advocate for family-friendly courtyard apartment buildings in my own community. This on-the-ground experience has deepened my understanding of urban development and helped me build the political and professional relationships that, I hope, will eventually lead to the construction of a courtyard block building in my neighborhood in the not-too-distant future.

Why does it matter if U.S. cities are family-friendly? Cities need families, and families need cities. When families concentrate in suburban counties, cities lose the population base necessary to sustain public safety, support essential services, and maintain infrastructure. The suburbanization wave of the 1960s hollowed out urban economies, weakened school systems, and depressed property values. Fewer families in cities means fewer eyes on the street, fewer students in local schools, fewer customers for neighborhood businesses, fewer homebuyers and workers, and fewer parents who are deeply invested in keeping public spaces safe and well-maintained. But if cities can create housing and neighborhoods that draw families back, they stand a far better chance of reversing the decline in school enrollment, shoring up public budgets, and generally revitalizing urban life.

Families need cities, too. While the boomer generation may not have fully valued walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, millennials and younger generations increasingly do. Many of us grew up in car-dependent suburbs that lacked distinctive architectural identity, public gathering places, social diversity, and access to arts and culture. Our lives were shaped by drive-to schools, big-box retail, chain restaurants, megachurches, and sports complexes. Today, the North Side of Chicago is teeming with millennial parents who originally came to the city for college or work, fell in love with its energy and character, and now pay a premium to raise their children here. Our city kids enjoy the early independence and agency made possible by proximity to schools, parks, friends, transit, places of worship, and neighborhood hangouts. They also grow up with the social richness that comes from encountering people of all backgrounds, ages, and stages.

To close this introduction, I want to emphasize that I’m an amateur in the field of urbanism. I’ve had no formal training in architecture or urban planning. My academic background is in literature: I hold a Ph.D. in English from Northwestern University, with a specialization in Renaissance English and Italian texts. My dissertation focused on pastoral literature in early modern England and Italy, and one day I may write a post exploring the connections between those scholarly interests and my current focus on urbanism. Much of my research centered on urban writers—such as Machiavelli and Shakespeare—who used the pastoral genre to examine aspects of city life and the urban–rural divide. I completed my dissertation shortly after having my third child in four years, and chose to pause my academic career to focus on raising my children. My courtyard urbanism advocacy picks up interest threads that I’ve held all my life, but it is a new and unexpected text in my life, and I’m eager to see where the plot will lead.

More essays from this writer can be found here. All image courtesy of the author.