Driving Toward Bankruptcy? L.A. Is Almost There

This article was originally published in 2013 in The Architect’s Newspaper as a warning that Los Angeles was headed toward a rapidly approaching fiscal breaking point. Nearly 13 years later, the Southern California region has done little to change course. The looming crisis—shaped by many forces, but driven in no small part by deeply flawed long-term land-use decisions made decades ago—now stands directly before us.

Driving Toward Bankruptcy (Recently updated, but—sadly—requiring only light revision.)

Fellow Angelenos, we must build a different city—or drive ourselves broke. According to the American Automobile Association, the average annual cost of owning and operating a car is approximately $12,300. Of that amount:

- ≈ 75% leaves the local economy; this includes vehicle purchases, gasoline, insurance, financing, and much of the depreciation flow to national or global firms.

- ≈ 25% stays local; this pays for local repairs and maintenance labor, some retail margins, parking, and local/state fees.

This high-level split aligns with analyses frequently cited by Strong Towns and transportation economics literature comparing auto spending with locally retained spending from walking, biking, and transit.

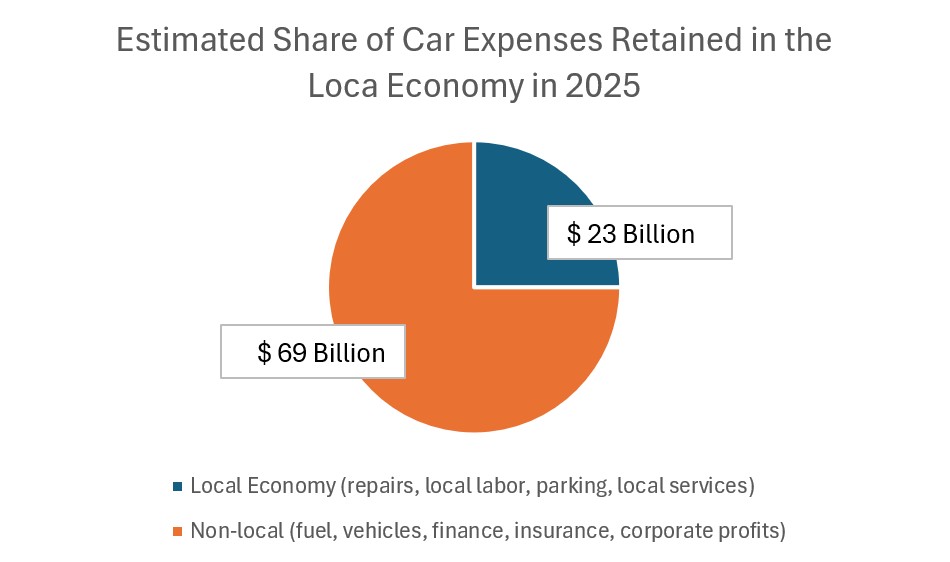

Let’s do the math. In 2023, LA County had 7.5 million registered vehicles. Since about 75% (or more) of the motoring cost flows out of the local economy, this means 7.5 million x $9,225 is not spent locally, which equals approximately $69 billion. This is the amount we are taking out of our local economy per year, every year, because we drive.

A simple pie chart illustrates this.

Decades of sprawl are rightly blamed for declining quality of life and soul-deadening congestion. It should also get a lot of the blame for our fiscal calamity. L.A.’s recent budget crisis prompted the city council to pass a resolution declaring a fiscal emergency and the creation of the Los Angeles Charter Reform Commission, tasked with modernizing city operations.

What’s missing is an acknowledgment that L.A. was an early adopter of the suburban development model—one widely described, most notably by Strong Towns, as a “development Ponzi scheme.” Postwar growth depended on continual outward expansion and public subsidies, using revenue from new development to pay for the deferred maintenance of existing infrastructure. As with any Ponzi scheme, early participants benefited disproportionately, while late-coming residents—often lower-income or minority communities—were left paying more for deteriorating services.

The result is a system that requires perpetual growth simply to avoid financial collapse. This structural imbalance went largely unnoticed during decades of sprawl, because each new wave of growth generated new money—but only once. Many communities quietly relied on development fees from new projects to maintain earlier ones, a strategy that worked only temporarily.

But L.A.’s era of outward expansion has effectively ended. There is little land left to sprawl into, and even high-rise construction in the urban core has slowed. At the same time, the specific form of density the city has pursued—often poorly integrated, disruptive, and inequitable—has fueled widespread NIMBY opposition. Yet inaction is not a viable alternative. The city’s current trajectory is a failure unfolding in real time, with economic consequences that are already becoming impossible to ignore.

Underlying our problems is a land-use balance so distorted that it cannot hold. In greater Los Angeles, we are using more than 60% of our land for our automobiles (roads, parking lots, landscape buffers, traffic islands, etc.). According to Christopher Alexander’s book A Pattern Language, the ideal percentage of land given over to automobiles in a city with balanced transit options is 19%–20% percent of the land area.

Examples of this more favorable pattern can be found in older neighborhoods of Boston, Brooklyn, or Philadelphia—areas largely built before the automobile took over the shaping of urban form. The benefits of this kind of land use are wide-ranging, but among the most consequential is its fiscal impact. In these neighborhoods, roughly four out of every five acres generate tax revenue, which is more than enough to maintain the shared infrastructure on the remaining acre devoted to streets, utilities, and public space.

In Los Angeles, the math is reversed. Only about two out of every five acres generate revenue, while the other three are consumed by roads, parking, and other nonproductive land uses. Those two productive acres must subsidize the rest. It is hardly surprising, then, that the city struggles to keep up with basic maintenance—even something as mundane as fixing potholes.

Rick Cole, the city’s former chief deputy city controller, said in a July 2025 interview with the Los Angeles Times: “I’ve never been more alarmed about the future of Los Angeles [and] the existential challenges facing the city, which have been decades in the making. Politics needs to look out at the future and not just react to the crises of the day. And Los Angeles needs bold, systemic reform to meet the moment.”

Cole focused his criticism primarily on city governance, aligning with Mayor Karen Bass’ call for a “fundamental overhaul of city government” to deliver the basic services Angelenos deserve. But given his background as a former executive director of the Congress for the New Urbanism and a frequent contributor to Strong Towns, he would likely agree that meaningful land-use and urban design reform must also be central to any truly overhauled L.A.

Governance, mobility systems, and the physical DNA of our communities are inseparable. The prevailing narrative claims that we are too big and too dense, with NIMBY groups blaming growth for most civic failures. Yet by opposing development, they also cut off the revenues that have sustained the city, while their resistance intimidates politicians wary of approving anything new. At the same time, Angelenos demand infrastructure on par with global cities. The passage of Measure HLA (Healthy Streets LA) in March 2024 reflects this contradiction, requiring the city to finally implement its 2015 Mobility Plan by adding protected bike lanes, bus lanes, and pedestrian safety features whenever streets are improved.

There is an active conflict over implementation. Some city departments are resisting, appeals are under way, and the debate keeps circling around how to rebalance space between cars, pedestrians, cyclists, and transit. But this misses the core reality: Los Angeles, in its current form, cannot afford to fully comply with HLA.

You cannot build effective public transit—or mandate a truly multimodal system—on top of a city fundamentally structured around the automobile.

You cannot build effective public transit—or mandate a truly multimodal system—on top of a city fundamentally structured around the automobile. This is especially true in L.A., which has exhausted its most important historical funding mechanism: growth. Even if such a system could be imposed, it would still fall short. Public transit only works at scale when it attracts sustained, high ridership. In a car-based city, residents are spread too far apart for enough people to walk to transit, and once individuals are already in their cars, too few will choose to transfer to rail or bus. The urban form itself suppresses the very ridership that transit depends on.

Metro describes this as the first-mile/last-mile problem. Many smart people are working on it, but the hard truth is that it cannot be fully solved by incremental fixes layered onto the city we have. The real solution is not to limp along with inherited urban form, but to build the city we actually need. Car-centric mobility is obsolete. We should be designing Los Angeles for 2075, not continuing to optimize it for 1975.

The right answer is density, even if density remains the least popular word in postwar suburban America. Too often, we deploy it as a verbal firebomb against new development. But done right, density is not the problem; it is the solution.

Not everywhere, of course—only within walking distance of transit stations. Concentrated in “walkshed” areas around transit, density generates the ridership that makes it viable. If Los Angeles Metro and the city were to fully embrace bicycling as an extension of walking, the effective catchment around stations (the “bikeshed” area) could expand, allowing each transit node to serve far more people without cars.

Taken together, this would dramatically expand L.A.’s non-car-dependent urban area. The result would be a moderately dense city—one that is strategic, humane, and efficient—that can comfortably accommodate current and future housing needs and support a healthier, more sustainable Los Angeles.

To offset concentrated development, the city could reduce density between transit lines, enough to create meaningful new open space. A better, denser, and more sustainable city does not mean density everywhere. It can also mean less density in the right places, and more parks. If we strike the right balance—higher density along public transit corridors paired with new open space elsewhere—we could once again create a city that the world admires and seeks to imitate.

Imagine bustling transit hubs surrounded by pedestrian zones, cafes, corner stores, markets, plazas, and a wide range of housing options. Now imagine those hubs separated by low-density areas: narrow residential streets, connected bicycle networks, community gardens, and generous parks. All linked by public transit, all supported by our near-perfect climate. And, yes, you could still drive, if you chose to.

This was once the vision for Los Angeles: the 1970s-era “Centers Concept.” Had it been fully realized, the region might today be admired worldwide. But L.A. never truly embraced it, held back by entrenched car culture, limited early transit, political resistance to density, and zoning that favored sprawl. Even with the recent Los Angeles General Plan pointing toward more concentrated growth, the city continued on a path of dispersed development with pockets of density rather than a true network of centers.

The Centers Concept remains a viable future for Los Angeles, especially as rail transit continues to expand. But it cannot be achieved through minor land-use tweaks shaped by a consensus that wants to keep driving while asking everyone else to get off the road.

The challenge of our time is to build grassroots YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) movements that push for fundamentally different solutions.

Real progress requires faster and more radical change, as well as public mobilization to demand it. The challenge of our time is to build grassroots YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard) movements that push for fundamentally different solutions.

Perhaps one reason that could convince car-love-stricken Angelenos toward a catalytic change is that we want to keep money in local pockets and contribute to a thriving local economy, with jobs and opportunities right here at home. In the 1940s, we used approximately 3 cents of every disposable dollar on one of the best public transit networks in the U.S.—yes, here in L.A. Today, we are spending 16.5 cents of every dollar not being able to move around much.

Angelenos without a car will have upward of 10% more money to spend, and probably will do so locally. If we could eliminate only 10% of the vehicles in LA County, we would infuse ≈ $7 billion a year into our local economy. Imagine what our city could be like with that kind of extra money circulating locally, year after year.

This is the choice now facing Los Angeles. We can continue to subsidize a failing, car-dependent urban model—exporting tens of billions of dollars a year, eroding public services, and edging closer to fiscal insolvency—or we can decisively reshape the city around transit, density, and local investment. The path forward is neither nostalgic nor utopian; it is practical, economic, and urgent. Build the city we need, keep money circulating locally, and restore opportunity and resilience. Or keep driving, quite literally, toward bankruptcy.

Featured image via Wikipedia Commons.