How Game Design Is Fostering Connection Between Nurses and Mothers-To-Be

Sean Ferry and I walked past the waiting room and into the OB-GYN clinic at St. Joseph’s Hospital, in Paterson, New Jersey. It was a Thursday afternoon in late July, around noon. A midwife saw us brush by and walked over to share her news. She knew we were working with Stephanie Mathews, an advanced practice nurse, on a game-like experience to improve communication in exam rooms between nurses and their early-stage pregnant patients. One patient, who had previous experience with abuse as a child and had shut down during her exam with a midwife, had just tried the game.

“The patient was refusing a pelvic exam,” the midwife said, “but Stefanie changed the whole vibe in the room.” Stefanie is our internal champion at St. Joseph’s. “I let Stefanie into the room for two minutes, and when I came back, they were laughing, and the patient asked about her delivery options.”

Sean is the director of innovation at St. Joseph’s Health and runs the Center for Innovation there. We had worked together over a decade ago at the innovation consultancy Fahrenheit 212. Since then, Sean has dipped his toes into my graduate classes at the School of Visual Art to teach sessions on creating narratives. In April, he sent a text asking if I had the time to help manage a game design project for the clinic. They wanted to look at solutions for how to get their pregnant patients from Paterson to ask more clinical questions in their earlier appointments. I have incorporated game design strategies into workshops, teaching, and designs since my time at Institute of Play in New York, but this would be the first time a game was a specific delivery for a brief. “We wanted it to be analog, because of the tactile sensation it creates,” Sean said. “We thought that would activate a different part of the brain. Plus, it needed to work inside a clinic exam room.”

Paterson is the most diverse community in New Jersey; nearly two-thirds of the population speak a language other than English at home. Many have limited access to healthcare. The team had tried a few game ideas out with Stefanie, but none resonated to the point of sharing it with patients. I pulled in a former graduate student of mine, Yuri Shin, who is a nurse-turned-user-experience-designer, to bring more tangible professional knowledge to the project. During our early time at the clinic, we met nurses and midwives, learned about the patient experience from an operational and clinical point of view, and dug into research.

During our research, a doula we interviewed in Brooklyn talked about how quickly she had to connect with her patients. “I can create intimacy and trust within a matter of minutes,” she told us. “I was a pregnant teen in a shelter at 17. Being personally vulnerable breaks down a lot of barriers.” Sharing that experience helped her patients get comfortable quickly.

“I had a doctor that had been through IVF [in vitro fertilization] as well,” said Kendra, a new mother. “This normalized our conversation for me.” We found this pattern with almost every new mother we spoke to: discovering shared experiences with their caregiver—such as experiencing loss, or being a woman of color in a hospital setting—helped them to let their guard down. So we took this idea into the clinic and proposed that we change the problem we were looking to solve. We shifted from trying to get patients to ask questions to creating a shared experience between patients and nurses. We thought this would build trust and reduce the power gap, and that once that happened, the questions would come. Now we just needed a way to do that.

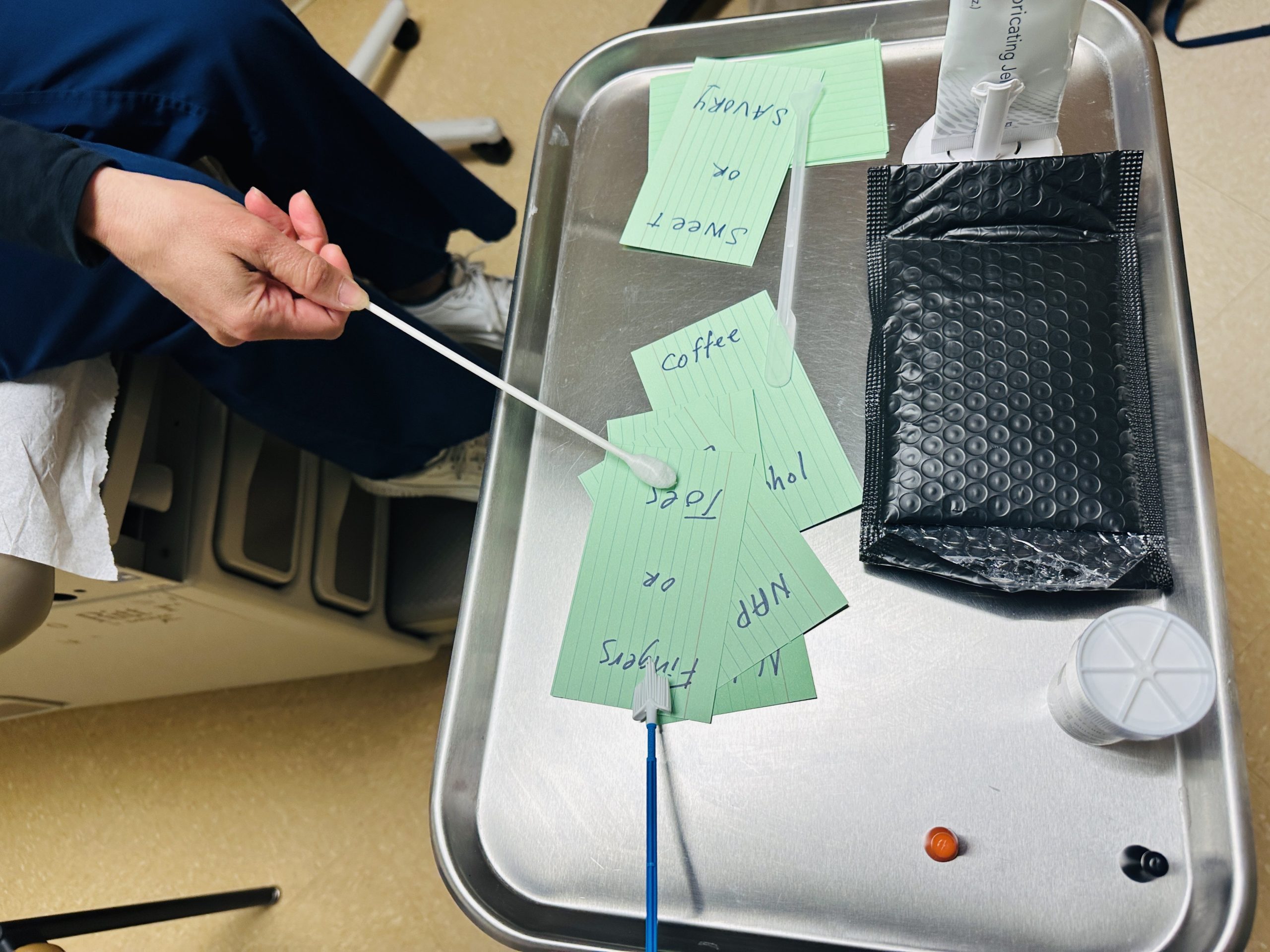

The first prototype of the idea that eventually became ¿Prefieres? was just words on index cards. Photo by the author.

The first prototype of the idea that eventually became ¿Prefieres? was just words on index cards. Photo by the author.

An early game idea involved prototyping with cardboard dominoes, but using conversation topics instead of dots. The response to the game was positive and provided a way for participants to share stories. However, the area of play could become cumbersome, and there were a lot of pieces to manage. Photo by the author.

An early game idea involved prototyping with cardboard dominoes, but using conversation topics instead of dots. The response to the game was positive and provided a way for participants to share stories. However, the area of play could become cumbersome, and there were a lot of pieces to manage. Photo by the author.

Over the course of the summer we looked at various games as starting points, searching for a simple mechanic (a game design term that denotes an action that creates the “play”) that could be used and easily explained in a clinical setting. We tried drawing in sketchbooks, modifying games like Dominoes and Mancala, even playing pick-up sticks with materials we found in the exam room drawers, like q-tips and pap smear swabs. Yuri suggested we try modeling a kid’s game called Would You Rather?, which gives players two choices to pick from, and then each player talks about why they made their choice. We made cards that illustrated pairs of words inspired from a list we had of questions that nurses had heard in past patient appointments. The pairings would have an indirect connection to potential clinical topics—coffee or alcohol, exercise or nap, natural or pharmaceutical, for example—and the nurses could take the conversations in that direction if necessary. It resonated immediately.

Community members, new parents, and other employees at St. Joseph’s Health participate in a game design workshop, which allowed them to play and modify the games we prototyped for use in the clinic. Photo by the author.

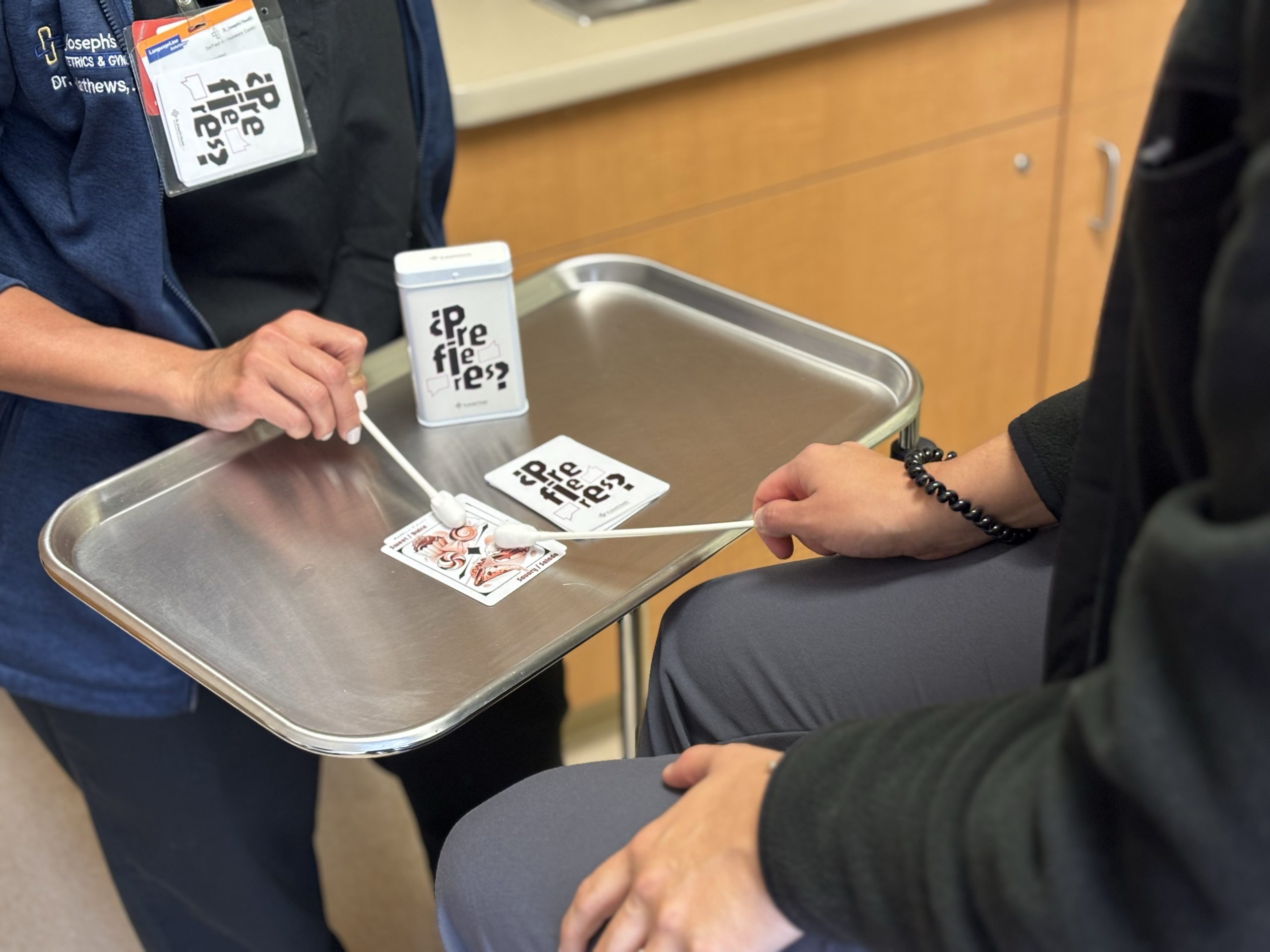

A nurse and a patient both use swabs as “pointers” to indicate their choice on the card. The illustrations on the cards were drawn by Kitty Sanchez, a graduate of William Paterson University. Photo by Sean Ferry.

Playing the game is simple. The cards are shuffled and placed face down on a surface. The patient and nurse each have a swab that acts as a “pointer.” The patient turns over the top card, revealing a pair of images to choose from, and at the count of three, both people use their swabs to point to which image they prefer. If both people choose the same image, the patient tells a story about why she chose that side, then the nurse shares her story. If they choose different images, the nurse tells the story first. Either way, both share something personal. The players rarely need more than two or three cards to start a longer conversation.

Early on, the simple mechanics and the low stakes of the topic pairs helped initiate quick conversations about shared experiences and often led to clinical concerns, such as how to relieve swollen feet after standing all day at work, or helping patients understand what an epidural is. We worked with Kitty Sanchez, a local female illustrator, and added both English and Spanish terms to create the backs of each of the eight cards. In our first week, after playing the game, one patient enthusiastically told Stefanie, “Next time I see you in the hallway, I’m going to say. ‘Hey, what’s up girl?’” After weeks of playing the game with patients and iterating on the idea, we conducted a workshop with the community where we had other hospital employees, mothers from Paterson, and members of the community come in to learn about the project and modify the game themselves.

The primary version of the game is carried by nurses in a plastic ID holder, taking advantage of an object the nurses are already wearing and making it highly visible to co-workers and patients. There is also a version that comes in a bandage tin that is kept in the exam rooms. Photo by Sean Ferry.

Now we have our first printed version, and nurses can carry the cards attached to a plastic badge case along with their other hospital IDs. The cards also sit inside the exam rooms inside a bandage tin. This fall we will run a pilot program with Stefanie in the clinic to measure the impact of ¿Prefieres? (“Would you rather?” in Spanish). We look forward to more patient stories like the young mother-to-be who, after playing a card and getting advice about how to take care of herself after standing all day for work, asked four or five other self-care related questions. Stefanie told us, “There’s no way the patient would have asked those questions otherwise.”

Featured image: Stefanie Mathews, with her student nurse, playing the final version of Prefieres, a game developed with the Center for Innovation at St. Joseph’s Health to create a shared experience and build trust between nurses and pregnant women in Paterson, New Jersey. Images courtesy of the Center for Innovation. Photo by Sean Ferry.