It’s 2026: Time for a Comprehensive Plan for New York City

Two pieces of news have recently grabbed the attention of those of us attuned to urban design and planning in New York City. The first was the word that the Adams administration, in its waning days, planned to shut down the Urban Design Division from the Department of City Planning (DCP). While DCP has long been criticized for its lack of proactive urban design and planning, the loss of the division seemed like the final nail in the coffin and an admission that the city had no interest in urban design.

On the other hand, the news that Andrew Kimball will be stepping down as CEO of the city’s Economic Development Corporation brings hope. Long seen as the epitome of the hand-in-glove relationship between City Hall and the real estate lobby, Kimball’s departure presents an opportunity for Mayor Mamdani to change the rules of the game and reset the relationship to one that supports communities and social value rather than the real estate industry.

To accomplish this, perhaps he could start with a comprehensive plan.

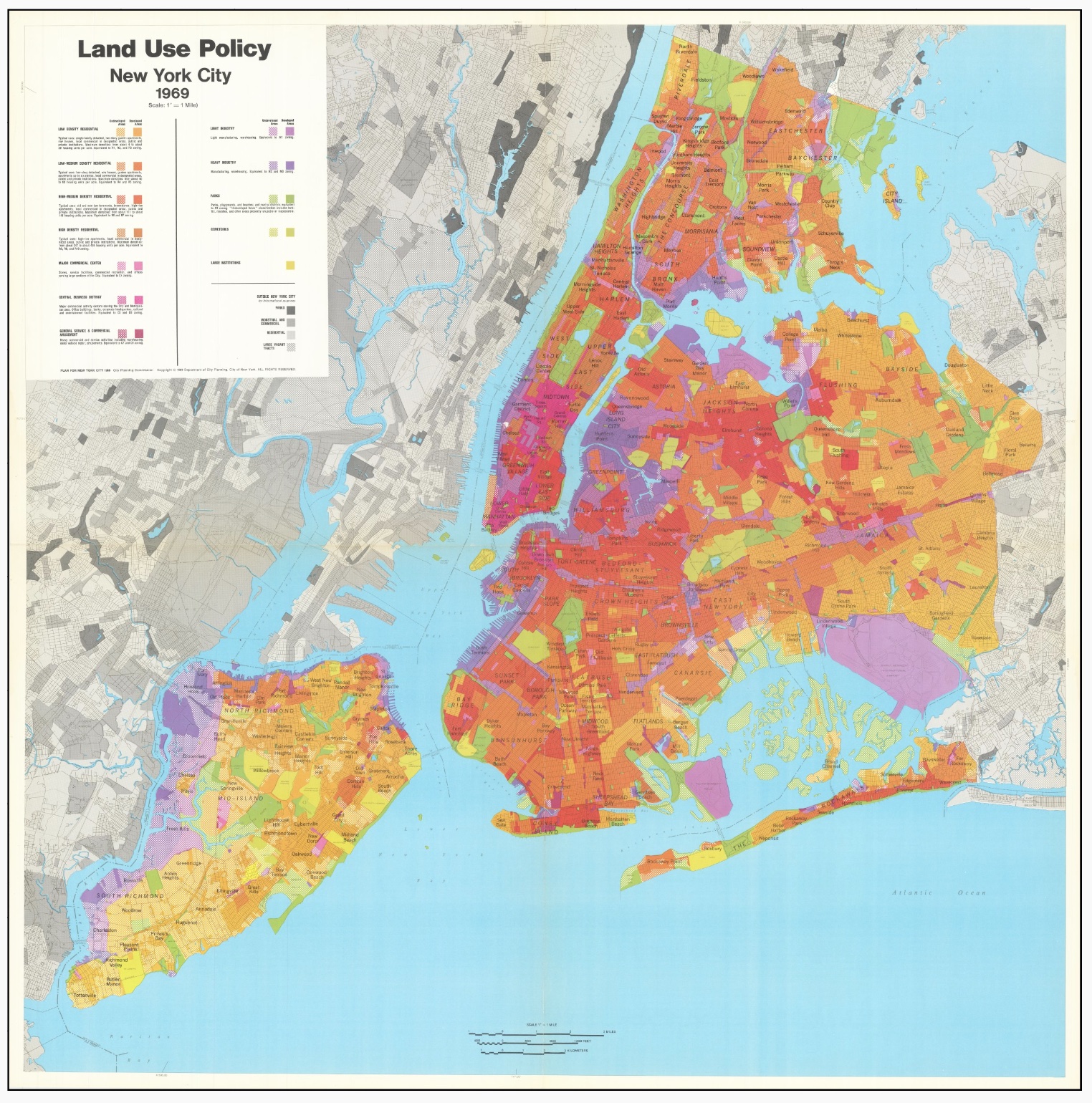

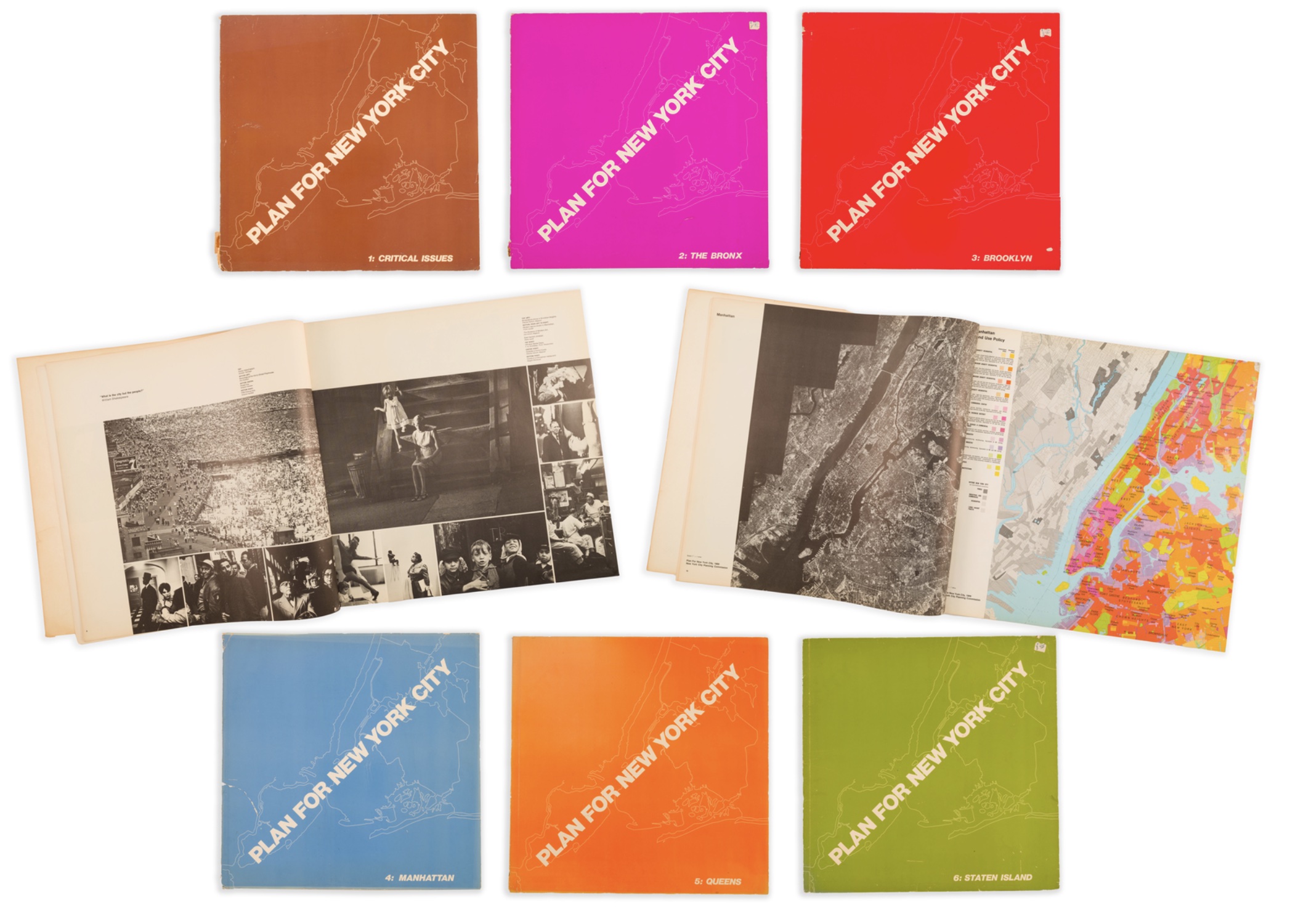

The 1938 revision of the New York City Charter called for a comprehensive plan, but none was produced until New York Mayor John Lindsay released one in 1969. Two motivations drove the plan: The first was that a comprehensive plan was required for the city to qualify for federal public housing funding. The second was that the plan embodied Lindsay’s approach to the city’s problems. It was not just a land-use plan but a comprehensive plan that attempted to address the serious problems facing the city and to make the best judgments and determine the best practices for the future. The plan was divided into six major sections:

- Volume 1—Critical Issues, an overview with 200 maps, 800 photographs, and 750 charts.

- Volumes 2–6, covering each of the city’s five boroughs (Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island, and The Bronx).

William H. Whyte, author of The Organization Man and founder of Project for Public Spaces, spent 15 months writing the 90,000-word Critical Issues volume. Donald H. Elliott served as chair of the City Planning Commission from 1966 to 1973 and oversaw the plan’s development.

Unlike many traditional master plans, this one was focused not on futuristic visions but on addressing the city’s current problems through realistic, implementable solutions. The plan emphasized:

- Social and economic issues alongside physical planning, including concerns like drug addiction.

- Processes for the city’s growth and governance.

- The creation of special zoning districts to preserve neighborhood diversity.

- The creation of 62 community planning boards, which were charged with developing needs assessments for their areas.

The 1969 plan has become something of a collector’s item—you can find copies on eBay for around $3,000.

While the plan was well-intentioned, it was met with significant opposition. After its release, the City Planning Commission held public hearings in all 62 community boards, but the plan became a lightning rod for protest. Critics felt it was presented as a fait accompli, without adequate community input. Coming after Robert Moses’ controversial urban renewal projects, top-down planning faced widespread skepticism.

This represents one of the paradoxes of the 1969 plan: It advocated for community participation and created structures to facilitate it (the 62 districts), yet its own development process didn’t embody those participatory principles, contributing significantly to its ultimate failure.

Mayor Lindsay was very interested in including a community participation component in the development process. Following the Moses era, which largely ignored public opinion, Lindsay wanted local communities to have an impact on government decisions before they were made. So the 62 Community Planning Districts were established as part of the plan’s framework for future community participation in planning, but they didn’t exist during the plan’s creation and therefore couldn’t provide input. The plan proposed these districts as a mechanism to decentralize planning going forward, but ironically, the plan itself was developed without that community-level input.

The reactions were wide-ranging. Some praised the plan as a strong and significant document, while others charged that it was merely a listing of problems rather than solutions. Critics cited the plan’s imprecise goals as evidence of the impossibility of comprehensively planning for a city as complex as New York.

At the Regional Plan Association’s 40th anniversary conference in 1969, more than 40 activists—including white, Puerto Rican, and Black protesters—disrupted the presentation to decry the lack of community participation in the plan by people of color.

The plan’s establishment of 62 community planning districts was criticized for making it difficult to pass significant initiatives and challenging the ability to plan comprehensively across the city. The plan faced pressure from both the real estate industry and civic groups. When Mayor Abraham Beame took office, he focused on the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, and the comprehensive plan was largely abandoned.

Ultimately, the plan failed to gain the public support needed for implementation, and the City Planning Commission abandoned its comprehensive planning efforts. The city’s 1975 fiscal crisis further rendered the plan obsolete. This failure marked a turning point, with planners shifting to more localized, neighborhood-scale projects. Notably, New York remains the only major U.S. city without a comprehensive plan.

So what can we learn from the 1969 experiment? While the plan ultimately failed to gain full implementation, it did produce several important benefits and innovations.

- The plan introduced the concept of special zoning districts, allowing neighborhoods to adopt regulations that would preserve their unique character and diversity. This proved to be one of its most enduring contributions. In 1970, the city used this special district method for the first time to preserve the South Street Seaport area and protect it from major development.

- The plan also represented a significant shift in urban planning philosophy. The goal was to make the city comfortable to live in, based on the needs of each community. This contrasted sharply with earlier top-down approaches.

- The plan provided an unprecedented comprehensive assessment of the city’s challenges and opportunities, with extensive data, maps, photographs, and analyses across all five boroughs.

- Though criticized for insufficient input, the public hearings held in all 62 of the city’s community boards set a precedent for broader community involvement in planning processes.

Tragically, the 1969 plan was never given a chance to be fully tested. Between the backlash at its launch, the subsequent fiscal crisis, and the continued opposition from real estate interests, the city was unable to update the plan and create the community board–to–City Hall relationship it envisioned.

Today, the community boards are still active (and now reduced to 59), but they do not fulfill the role that the plan intended.

Under the 1975 City Charter, DCP formalized the 59 community districts into which the city is now organized. Community boards initiate the citywide budget process by preparing annual “District Needs Statements” and budget requests for their districts for both capital and expense budget items. Each board consists of up to 50 appointed, volunteer, unpaid members reflecting the varied makeup of the community, and a small staff headed by a district manager. The district manager convenes a district service cabinet of city agencies to coordinate their activities with respect to the district. The board is organized in committees addressing the issues important to its district and typically meets once a month to consider matters brought to it by its committees and to hear from local elected officials, members of the community, and other interested parties. Although the role of the community boards is advisory, in 1975 the City Charter was amended to specify their participation in the review of proposed changes in land use. Section 197a provided for the board to be able to create plans for consideration by the city, and section 197c established ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) for the review of various types of applications.

Regrettably, the good intentions implicit in the City Charter regarding the role of the community boards in neighborhood planning were never fully realized. This can be attributed to two main failings. The first is that the charter mandate to provide “technical support” to the boards—laid at the door of both DCP and the borough presidents—was never fulfilled. In the latter case, this was probably due primarily to lack of funding (another “unfunded mandate”), while the former may have had more to do with DCP’s desire to retain control of the planning process within its own ranks.

Many community boards did, nevertheless, undertake “197a plans” pursuant to that chapter of the charter. Professional consultants were hired to fill the gaps in the lack of technical expertise within the boards. At considerable expense and effort, a number of such plans were duly submitted to DCP.

You have only to read the process described in the charter and excerpted above to see why the plans have not been implemented in any significant way. After a tortuous review and approval process involving DCP, the borough president’s office, the City Planning Commission, and the City Council: “Copies of approved plans shall be filed with the city clerk, the department of city planning, the affected borough presidents, the affected borough boards and the affected community boards.”

Where of course, they die.

Today, the atrophy of the role of the boards in physical planning is perhaps best described by the city’s own website, which states: “While the main responsibility of the board office is to receive complaints from community residents, they also maintain other duties, such as processing permits for block parties and street fairs.”

So the community boards suffered from a lack of technical expertise (or funds to secure it) and a role in city planning that was merely advisory. Any chance of comprehensive planning was further thwarted by moving authority for the city’s capital budget away from DCP to the Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget). The neoliberal policies of the city after the fiscal crisis did little to support the idea of comprehensive planning and further atrophied the role of the community boards in planning decisions.

Since 1975, we have seen the consolidation of a process in which major planning is initiated by private real estate and implemented with very limited input from the local communities affected. There is no comprehensive plan to provide guidelines for influencing private development. Even when development is city-sponsored, the criteria for success are based on “best and highest use”—i.e., the most return on investment—rather than on community needs.

While there seems to be little enthusiasm at City Hall for a citywide comprehensive plan, and the current community boards and DCP probably lack the resources to produce one, there is one recent ray of hope in the Comprehensive Plan for Brooklyn.

Source: Brooklyn Borough President.

Under Borough President Antonio Reynoso, the first Brooklyn Plan was published in 2023. With help from the Regional Planning Association, the New York Academy of Medicine, and Hester Street Collaborative, the plan sought to fill a void left by the lack of a city plan since 1969. As the borough president put it: “We don’t plan, we just zone. We add housing here, we open up a new school there, and we make piecemeal changes that fail to think of the bigger picture. We deepen disparities instead of solving for them.”

The Brooklyn plan begins by setting out a comprehensive record of “existing conditions” in the borough, from Greenpoint in the north to Coney Island in the south, including data on demographics, socioeconomic status, health, land use and built form, housing, transportation and utilities, and environment. The plan concludes with a series of recommendations designed to address the disparities identified in the existing conditions and to guide evaluation of future development in the Borough. It is a fascinating document full of compelling data that should be used as the basis for planning.

The plan could be criticized for the same lack of input from the borough’s 18 community boards, which still lack the resources and technical expertise to fulfill that role. To address that deficit, the plan drew on the Regional Planning Association and the Academy of Medicine for the majority of the existing conditions data, and then used an “advisory committee” comprising 25 nonprofit, government, and academic institutions to provide input and recommendations. When the Draft Existing Conditions Report was issued in 2022, Hester Street Collaborative joined to develop a plan for community engagement and input. This led to a series of focus groups and an online survey, with a full presentation to the community boards in 2023. In late 2023, the Plan was submitted to DCP and the City Council.

Where, of course, it died.

The Office of the Brooklyn Borough President has only a limited role in the city’s land use processes, which are largely centralized in the Mayor’s Office and the City Council. The BP’s office has no authority to direct DCP and has a very limited budget of its own. Any proposals from City Hall can be reviewed but not thwarted by the borough.

2025 saw the release of round two of the plan, which provides updated analyses and incorporates feedback on the 2023 version. This is exactly what a plan should do, and what the 1969 plan did not live long enough to do.

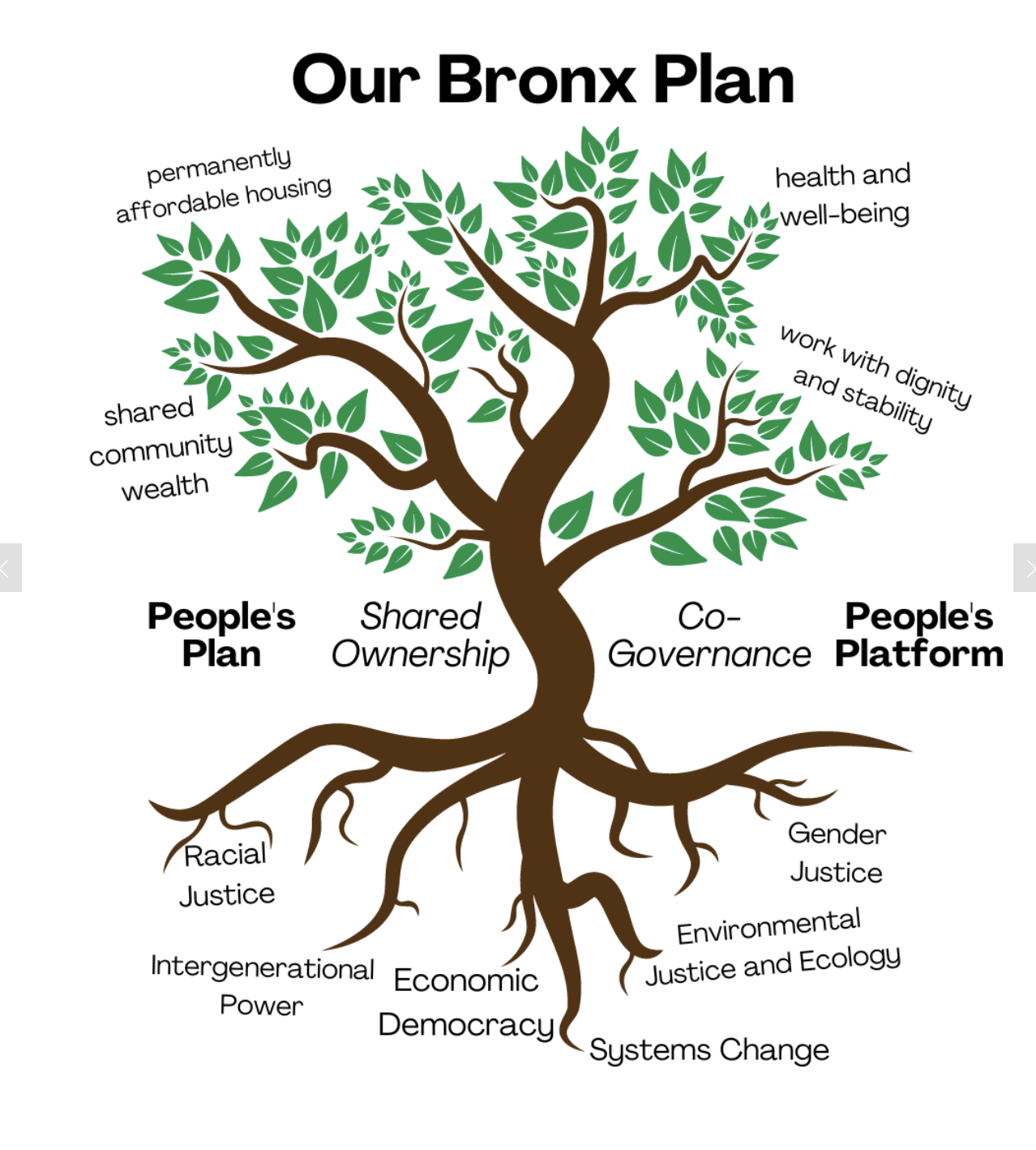

While the borough president initiated the Brooklyn plan, another plan in the Bronx was more “bottom-up” than “top-down.” A coalition of community-based organizations began collaborating after the pandemic of 2019 to promote economic recovery for their communities in the Bronx.

Source: The Bronxwide Plan.

That plan, completed in 2023, proposed policies and programs to support economic well-being and social justice for the citizens of the Bronx, where economic and social disparities have prevailed for decades.

Source: The Bronxwide Plan.

Unfortunately, as with the Brooklyn plan, the Bronx plan has not garnered significant attention from City Hall. Nevertheless, the Bronx plan and the coalition continue to speak out to support social and economic justice for their communities.

Is comprehensive community-based planning an idea whose time has come? Could a Mamdani City Hall put the power of the administration behind these community-based efforts? Could the Economic Development Corporation be repurposed so that its mandate is to support the implementation of community priorities rather than real estate interests? It does not seem too much to ask. On January 22, 2026, the Planners Network, hosted by Pratt Institute, will hold a panel discussion on this question, titled “A Comprehensive Plan for NYC: Could Its Time Be Now?” The answer is YES!