Los Angeles and the Density Paradox

Recent housing legislation aims to dismantle the dense web of regulations born from Americans’ longstanding distrust of urban density. Yet that aversion is not entirely misplaced, as much of U.S. densification has been poorly executed and is often implemented without coherent spatial or infrastructural frameworks. The results are environments that reinforce public resistance rather than alleviate it.

This resistance stands in stark contrast to our nation’s celebrated “can-do” ethos: the tradition of innovation, adaptability, urban reinvention. Entrenched NIMBY opposition and decades of legislation attempting to contain it has curtailed our ability to address contemporary urban challenges. Progress requires understanding the sociocultural and psychological roots of this resistance—the fears, perceived losses, and concerns that drive it.

A central driver of NIMBY opposition is the fear of losing personal mobility. For many, particularly car-dependent residents, increased density implies congestion, inconvenience, and a loss of autonomy. Transit-oriented development is often presented as the rational remedy: higher densities near transit nodes sustain ridership and reduce automobile dependence. Yet these positions are rooted in incompatible spatial logics and cultural attachments to mobility, and attempts to reconcile them frequently produce counterproductive outcomes. This tension is the density paradox: the very conditions required to make transit successful are those most likely to provoke resistance from existing residents. Overcoming this paradox is essential if urban communities are to progress collectively.

People frequently invoke Manhattan as a cautionary example of density’s excesses. However, its reality sharply diverges from this caricature. Despite its intensity of occupation, Manhattan maintains few private cars per capita, abundant public open spaces, vibrant economic activity, and remarkable social diversity. Mobility without a private vehicle is not only possible but often preferable, enabled by an integrated system of transit, taxis, cycling, and pedestrian infrastructure.

Manhattan’s population density—about 67,000 residents per square mile, or roughly 105 people (40 households) per acre—stands in stark contrast to that of coastal Los Angeles neighborhoods, where opposition to densification is loudest. There, densities average around 11,000 residents per square mile, about 17 people (seven households) per acre. The paradox is striking: those most resistant to density often inhabit environments that are, by global standards, remarkably low-density. This disparity reflects cultural, spatial, and infrastructural frameworks rather than innate human preferences: even low density becomes intolerable when poorly designed and unplanned.

Density is both a measurable and a perceptual phenomenon. While Los Angeles is sometimes described as among the densest U.S. urbanized areas, largely due to traffic congestion, this perception conflates vehicular congestion with urban population density. Unlike New York’s heterogeneous urban form, characterized by highly concentrated nodes interspersed with low-density areas, L.A. exhibits a more uniform pattern of moderate density spread across a vast territory. This uniformity, coupled with car-oriented mobility, amplifies the perceived intensity of crowding.

Aerial image of Los Angeles. It represents remarkably low densities spread over a huge area, with little open space left. Source: Adrian104/Wikimedia Commons.

Urban density debates often fail to recognize how perceptions of density are shaped by prevailing transportation networks. While psychologists have long studied cultural differences in personal space, they rarely consider how mobility cultures mediate these perceptions. In societies where mobility is synonymous with the private car, the sense of personal space expands to include the car’s own spatial footprint: driving lanes, parking spaces, buffer spaces. This inflated spatial expectation profoundly shapes how density is perceived and judged, embedding transportation habits within broader cultural notions of comfort, autonomy, and territoriality.

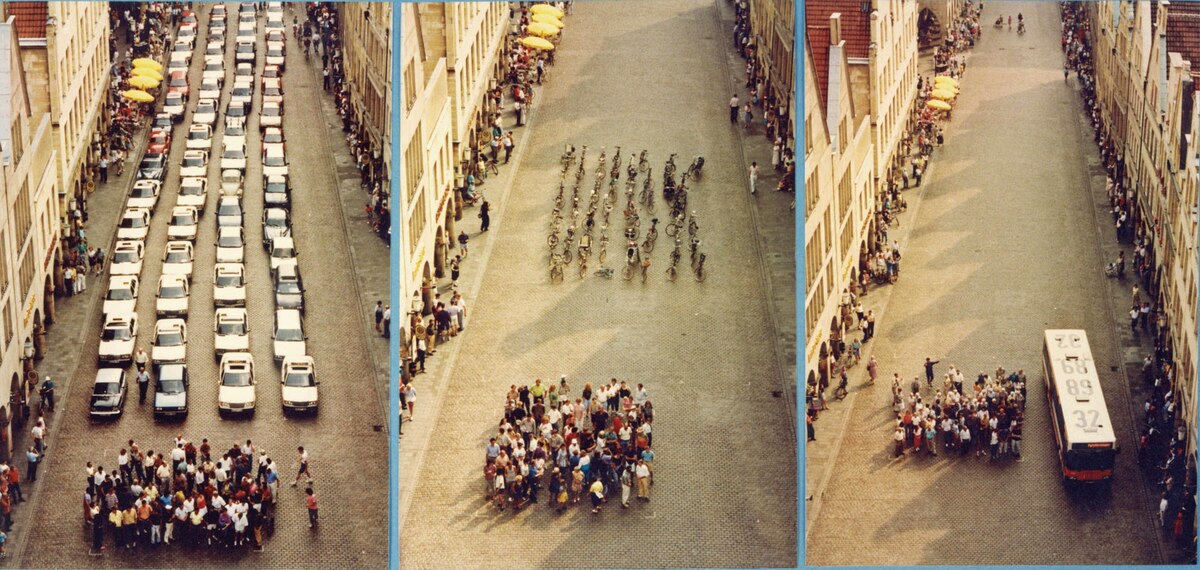

Look at this image created by the Muenster, Germany, planning office in the 1990s. With 60 people in their cars, the street is completely congested. But with the same 60 people on a bus, or on bikes, the street feels almost empty. This image has become so well-known you can find it everywhere online when people are discussing the congestion caused by automobiles.

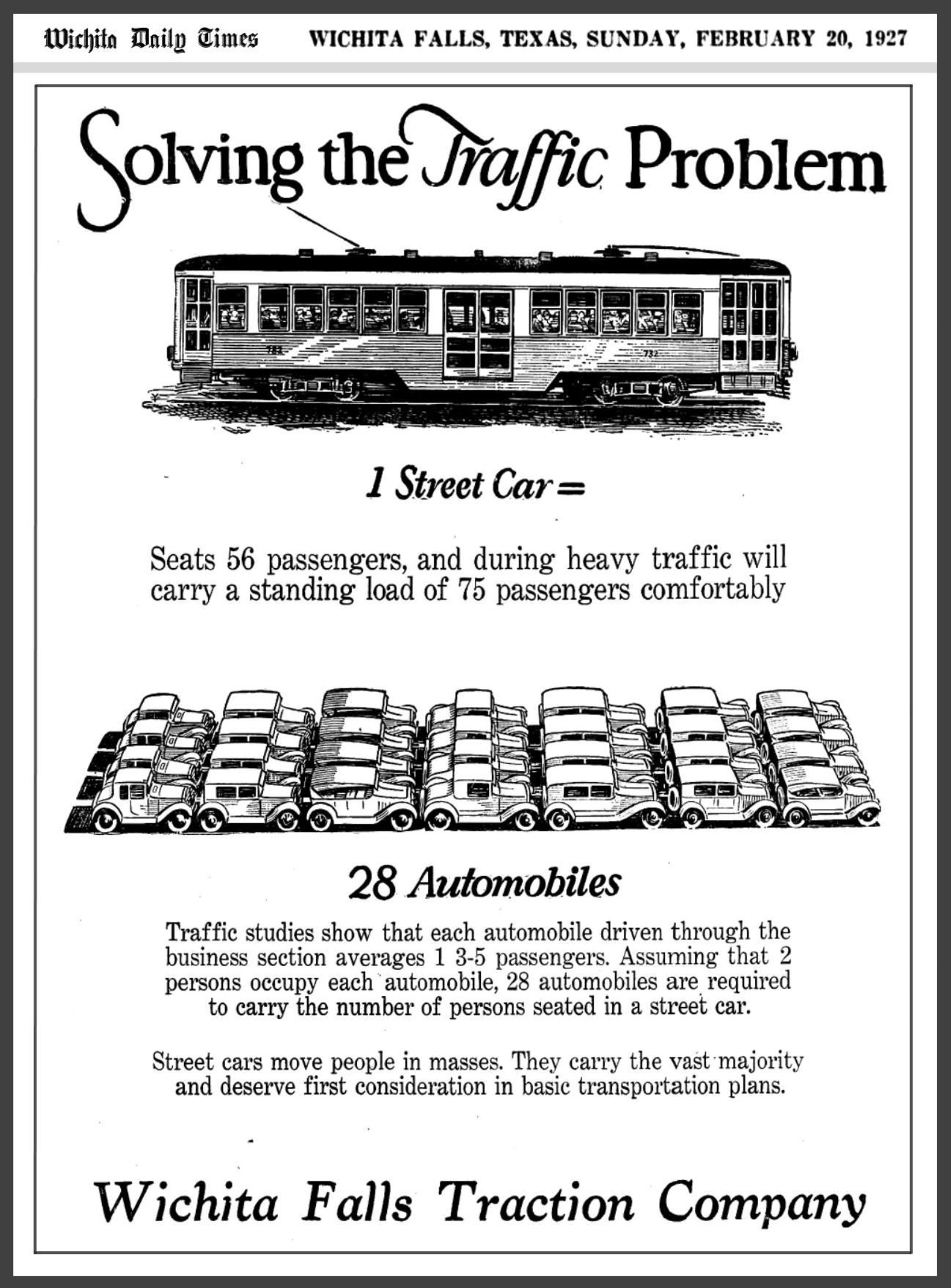

Cars always were, and forever will be, voracious consumers of space. This fact was not lost on people at the dawn of the car age—as we can see in this nearly 100-year-old graphic.

1927 advertisement for the Wichita Falls Traction Company.

We forgot about the spatial implications of car use for decades, until recently. During 2014’s European Week of Sustainable Mobility in Riga, a group of Latvian cyclists showed that cars take up way too much space, as seen in the image below. Point made!

Source: Artūrs Pavlovs of Let’s Bike It.

In cities built around the automobile, an excessive share of land is devoted to moving and storing vehicles, often at the expense of spaces for living and social interaction. As Donald Shoup and Michael Manville showed in their 2005 paper “People, Parking, and Cities,” roughly two-thirds of Los Angeles’ total land area is dedicated to roads and parking, compared with about 36% in Manhattan. A Pattern Language, Christopher Alexander’s classic guide to human-scale urban form, suggests an optimal figure closer to 19% for small-to-midsize cities. The contrast reveals how car-oriented urbanism has profoundly distorted the spatial balance between movement and dwelling, reshaping both the social and experiential fabric of urban life.

These figures also reveal vast opportunities. If Los Angeles were to reclaim even a portion of the land currently devoted to automobile infrastructure and restore it to more balanced, human-centered patterns of land use, it could unlock enormous potential for new housing and much-needed public open space. For over a century, it has been clear that such spatial efficiency is best achieved through rail-based transit. Trains remain the most economical users of space per person transported. With the passage of Measure R in 2008, Los Angeles County committed to rebuilding its rail network. The question, however, is whether this renewed investment in transit has translated into a more coherent, livable, and equitable urban environment.

Correcting these spatial and infrastructural imbalances cannot be achieved simply by expanding rail networks. When inserted into cities shaped by automobile dependence, rail systems often operate as square pegs in round holes—technically present but socially and spatially misaligned. Effective transit demands a compatible urban form: compact, mixed-use, and walkable districts organized around stations, where the car’s dominance is intentionally limited. Yet progress toward such environments has been slow, hindered by entrenched land-use patterns, lack of knowledge about adaptable models, regulatory inertia, and persistent NIMBY resistance. Without a coordinated effort to reform not only mobility systems but also the spatial and cultural foundations of car-oriented urbanism, transit investment alone will fall short of meaningful transformation.

NIMBY opposition ultimately arises from fears of spatial and social congestion. The density paradox helps explain this: the point at which density becomes intolerable depends on the dominant mode of transport. In car-oriented environments, where personal space extends to the vehicle and its buffers, even slight increases in density feel intrusive. Addressing NIMBY resistance thus requires more than policy reform; it demands a cultural redefinition of space, mobility, and proximity in urban life.

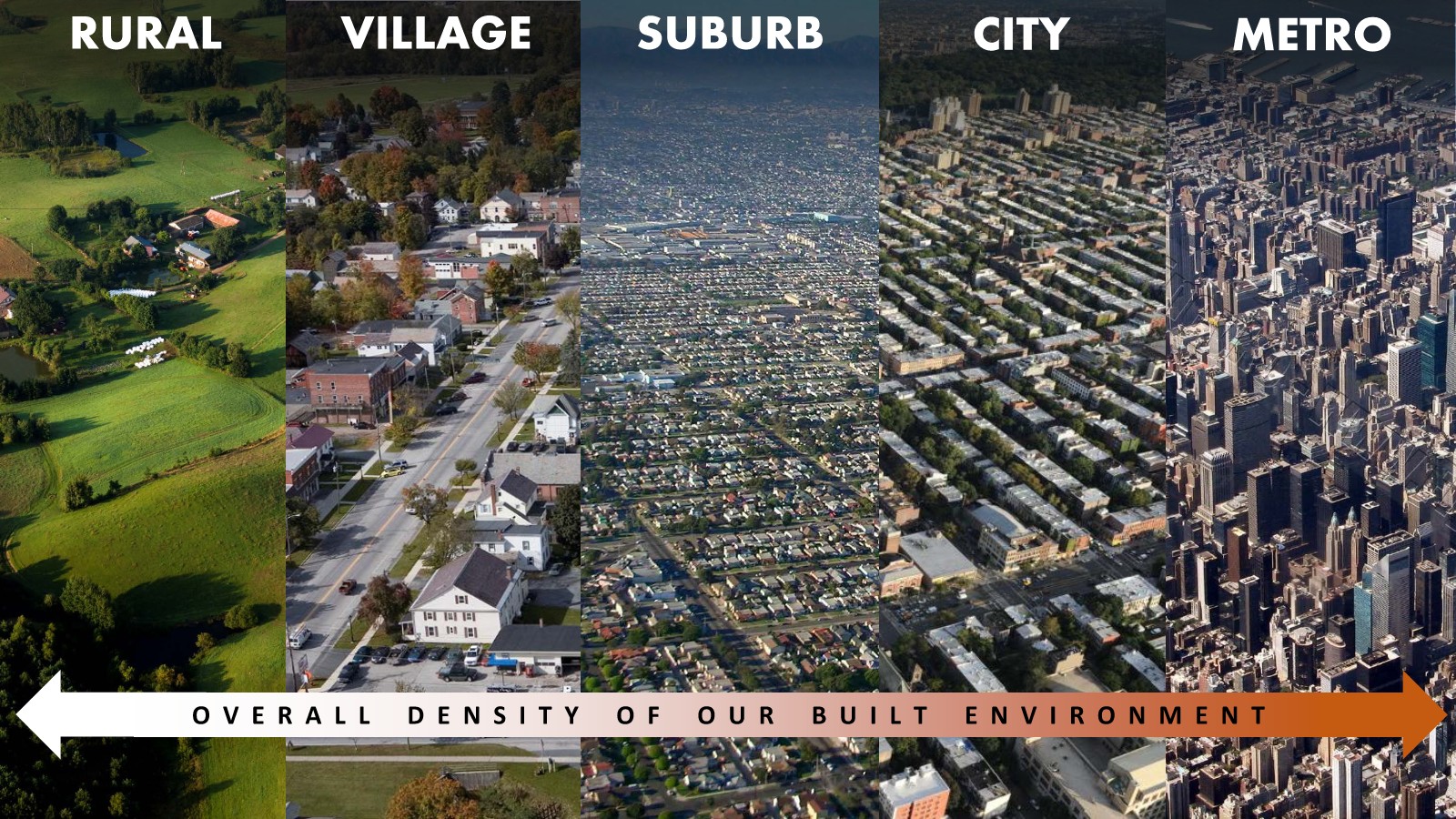

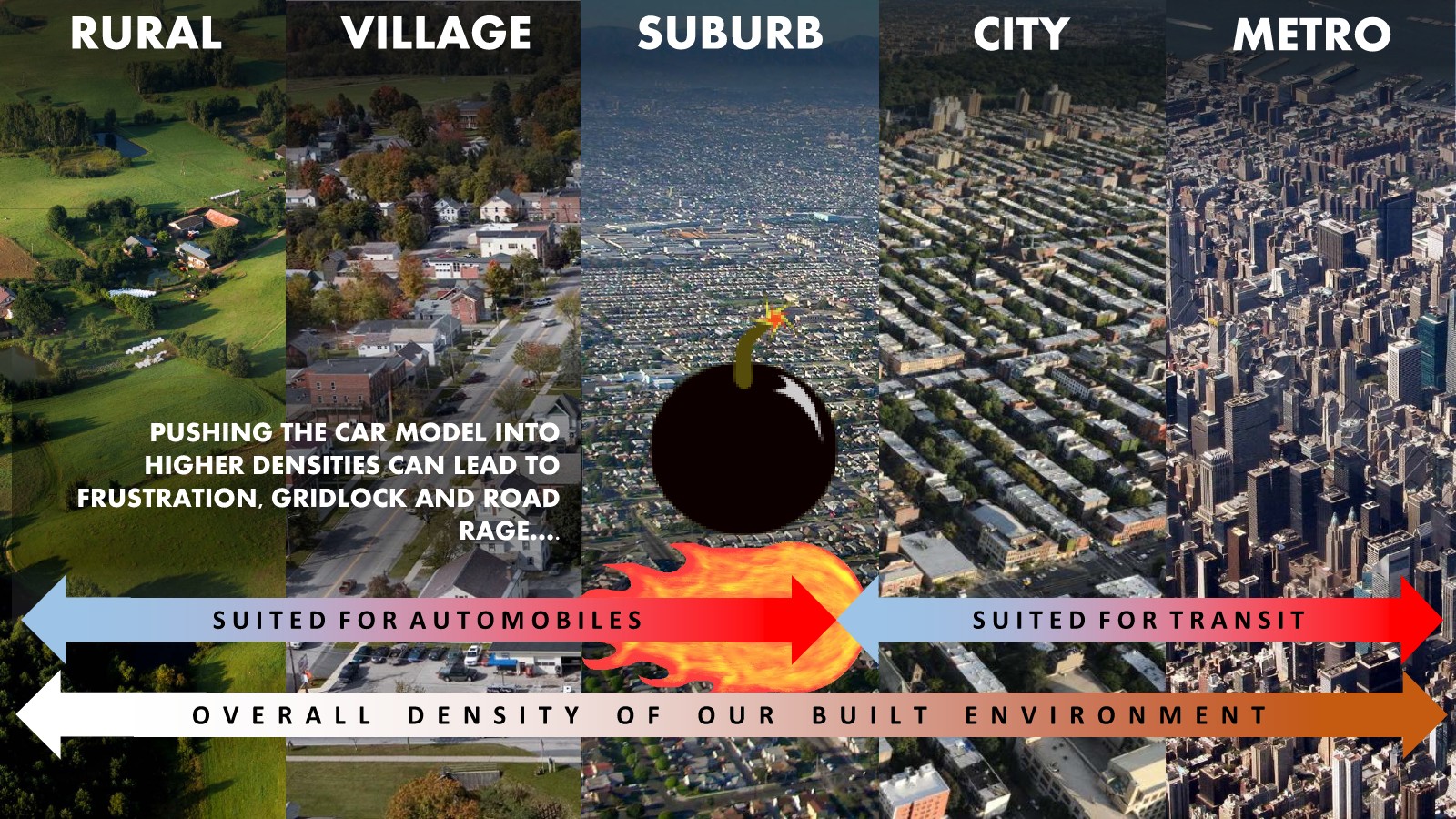

Here’s a basic density scale of human communities, from extremely rural land up to the metropolis. Humans without cars can happily function in all of these densities.

Image by author.

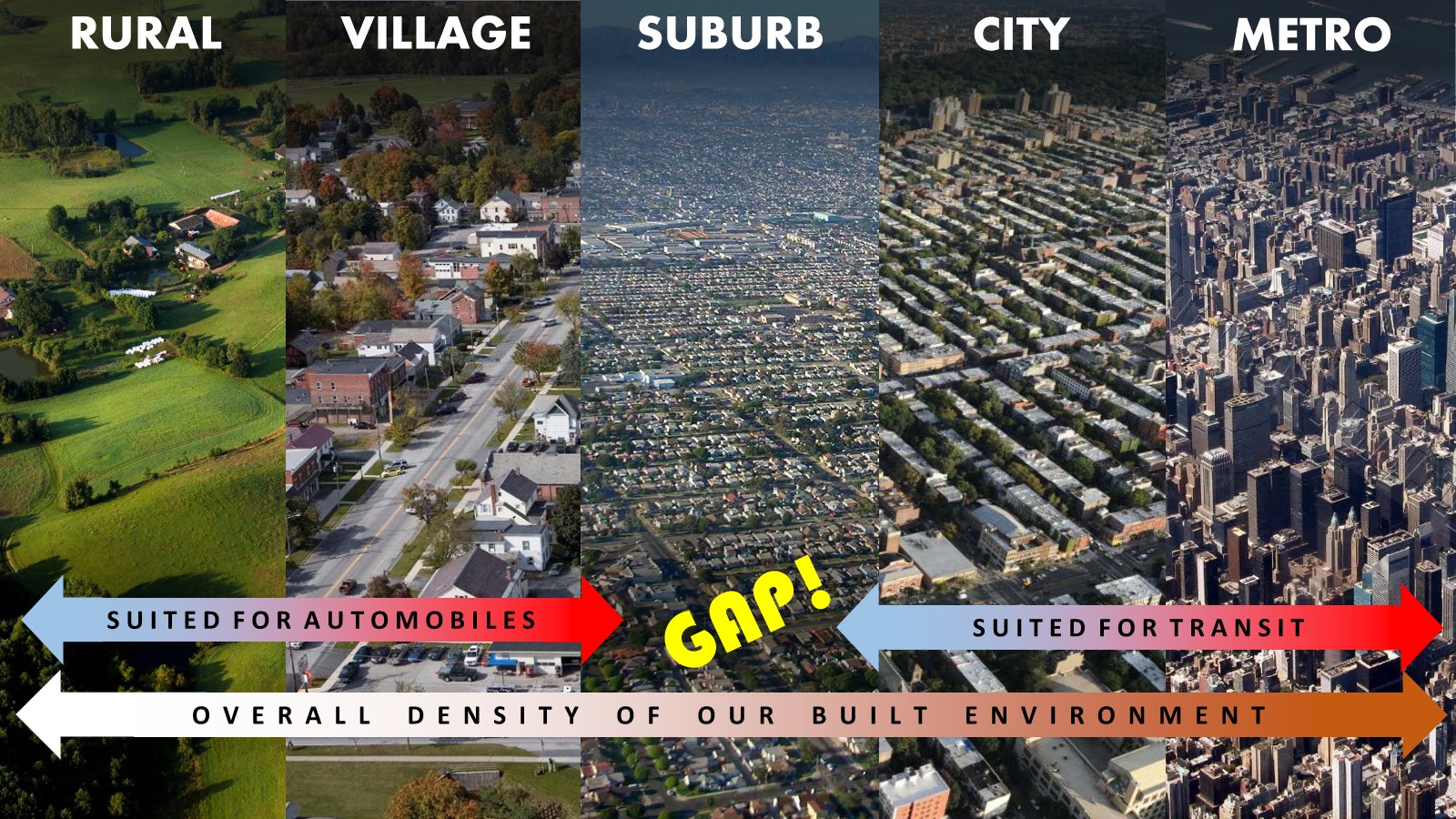

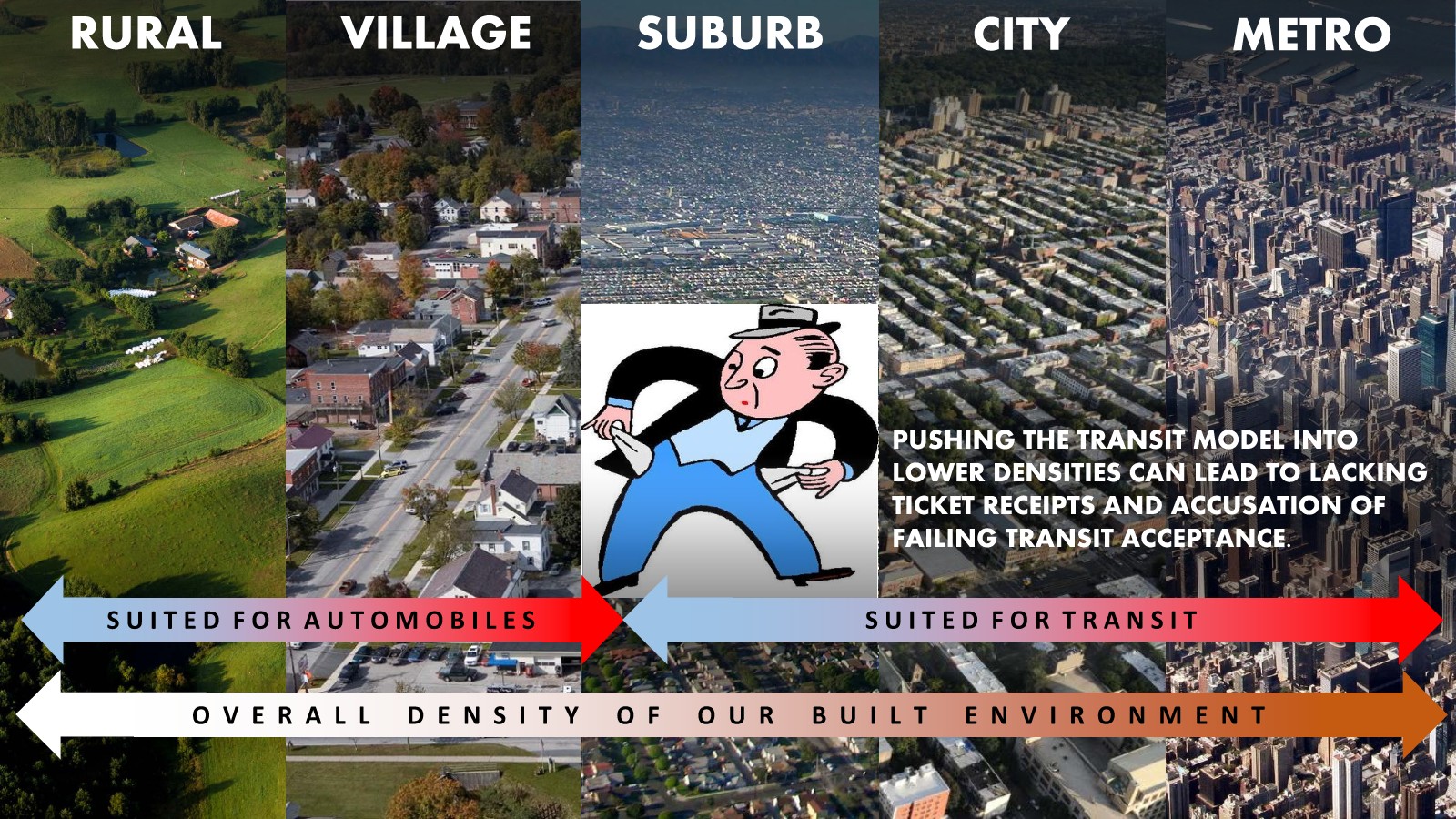

Once cars enter the picture, their efficiency is largely confined to rural and low-density suburban areas. Public transit, by contrast, scales well from moderately dense cities to bustling metropolises. Between these two models lies a gray zone, where neither system functions optimally. Los Angeles, along with many other U.S. cities, occupies precisely this gap.

Image by author.

Large suburban cities like Los Angeles are caught in a bind: too dense for cars to function efficiently, but not dense enough for transit to succeed. Transitioning from one model to the other is easier said than done.

Imagine a community that upzones in anticipation of future transit. Without the transit in place, residents remain car-bound, demanding parking and wide roads—features that undermine the very idea of a walkable, transit-oriented district. But building transit first brings the opposite problem: low-density areas cannot sustain ridership, making new lines appear inefficient and fueling claims that “transit doesn’t work” in such contexts. This mutual dependency between density and transit exposes a fundamental dilemma in urban planning: progress on one depends on the other moving in step.

Images by author.

This is the density paradox, a no-win scenario. Our streets are already overloaded with cars, yet we lack the density needed for transit to work effectively. Still, moving beyond this stalemate is essential.

The first step is recognizing that automobile- and transit-oriented cities rest on fundamentally different urban logics—they are distinct in space, movement, and social life. Progress in Los Angeles requires embracing multiple urban typologies within a single metropolis: allowing car-dependent areas to contract while expanding walkable, transit-oriented districts that strengthen one another. This transformation requires a cultural shift in how residents imagine their city and political leadership capable of sustaining long-term change despite NIMBY resistance and short-term discomfort.

At its core, NIMBY opposition reflects legitimate concerns about quality of life. Residents’ wariness of urban change is often justified: past “improvements” have too frequently led to overcrowded streets, strained infrastructure, and localized burdens, while benefiting mainly outside interests. Efforts to densify Los Angeles without a coherent, shared vision that frames such changes as part of a citywide strategy to improve conditions for all stakeholders are likely to deepen, rather than ease, resistance.

Building this new narrative must start with integrating urban and transportation planning, and rapidly delivering a fully realized and coordinated local example of a walkable, transit-oriented area in Southern California. In other words, we need to see and experience a successful pilot project to believe all the theories. When residents experience these environments firsthand, they can see how density—paired with thoughtful design, efficient mobility, and a clear public purpose—enhances quality of life, fostering broader support for transformative urban development.

This is not a call for timid half-measures that cling to the automobile city. Creating truly walkable, transit-based communities requires a wholesale rethinking of urban form: new zoning, innovative public and other open spaces, novel building types, and a deliberate redefinition of the car’s role within these districts. Progress demands learning from successful models, domestic and international, rather than tinkering with the automobile-oriented frameworks that created the current challenges. Only a bold, evidence-driven approach can produce transit-oriented districts in Los Angeles that are coherent, livable, and resilient.

The city has already missed opportunities for integrated transit-oriented development. Playa Vista, for instance, features walkable streets and sufficient density to sustain transit, yet no transit infrastructure has been planned or implemented. As the community fills, increased automobile use—and thus further congestion—is the likely outcome, rather than the sustainable urbanism its design could support.

Reclaiming land from cars is essential. Los Angeles has about 3.5 parking spaces per resident, an area 10 times larger than Long Beach and Santa Monica combined.

Reclaiming land from cars is essential. Los Angeles has about 3.5 parking spaces per resident, an area 10 times larger than Long Beach and Santa Monica combined. Even modest reclamation of this vehicle-dedicated space could unlock vast land for public space and transit-oriented development. Not all of it should become denser housing; a balanced strategy pairs compact, transit-adjacent districts with ample open space. Market tools like Transfer of Development Rights can direct growth toward transit hubs while turning surplus asphalt into parks.

Reimagining urban mobility also requires shifting from private car ownership to mobility-as-a-service models. Ride-hailing and car-sharing reduce the total number of vehicles and parking demand, freeing significant urban land. Minimizing reliance on private cars while pairing higher-density development with walking, cycling, and transit infrastructure, alongside expanded public space, can transform NIMBY resistance into participation.

Tackling Los Angeles’s urban challenges requires a coordinated, multiagency effort that addresses both the physical and perceptual barriers to density. Resistance arises less from numbers than from ingrained mobility habits and spatial expectations. Overcoming it means reframing how Angelenos conceive space through well-designed, walkable districts, reclaimed land, reallocated development rights, and mobility-as-a-service. Success depends on sustained political will and learning from proven global models. By aligning transportation, land use, and public perception, Los Angeles can turn the anxiety over density into an opportunity for sustainable, shared urban prosperity.

Feature image: photo by Remi Jouan, via Wikimedia Commons.