New York City—the Metropolis Built on Water

I don’t know if I can accurately characterize photographer Stanley Greenberg’s interest in New York City’s water infrastructure as an obsession, based on a single phone conversation, but it’s clearly been a decades-long preoccupation. His new book, Waterworks: The Hidden Water System of New York (KGP/Monolith), explores the often hidden-in-plain-sight structures, equipment, and access points responsible for bringing water into and out of the city: reservoirs, aqueducts, tunnels, gatehouses, pumping stations, water tanks, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater facilities, and maintenance covers. The book includes a separate fold-out map charting more than 400 locations, from upstate to Long Island, as well as a QR code–enabled digital map offering even more detail. Recently I spoke to Greenberg about the genesis for the new book, his battles with city bureaucracy, and the seminal influence of water on the history of New York City.

MCP: Martin C. Pedersen

SG: Stanley Greenberg

Tell me the origin story of this beautiful book.

The first edition of Waterworks [Princeton Architectural Press, 2003] was a follow-up to my first book, Invisible New York [Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998]. It was about all kinds of hidden places in the infrastructure of the city. There were some water supply sites in it, and I thought, This system is so big that I want to do a book just about water.

I had helped reorganize the water system archives overseen by DEP [NYC Department of Environmental Protection] for a year with some people from Cooper Union. We catalogued and conserved this incredible collection that had been neglected for decades. We found drawings from 1840, and I cataloged more than 10,000 photographs. So I knew the system and started going out to sites. First I asked permission, and for years they said no, then they asked me for a list of where I wanted to go and freaked out: “You know too much about the system, you’re a security threat,” they told me.

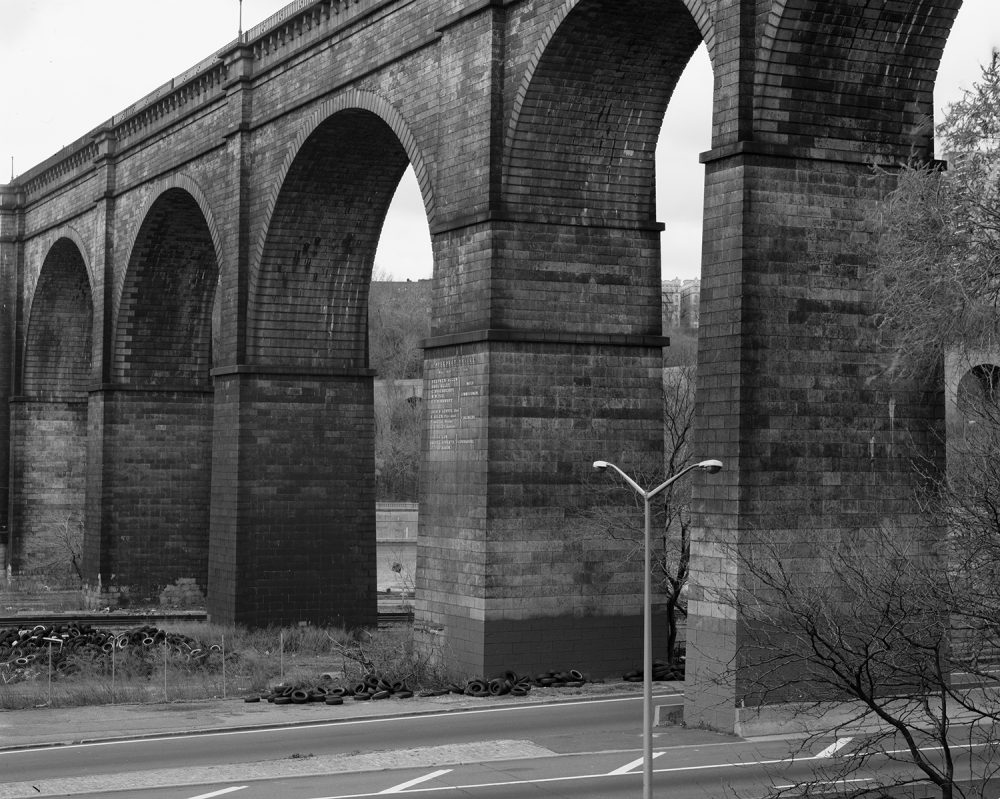

High Bridge, Bronx and Manhattan, 2000.

High Bridge Tower, Manhattan, 1995.

Even though you’d worked for the city?

I worked in city government for eight years in many agencies, including DEP. In my last job I was an assistant commissioner. I was not an unknown quantity, but it didn’t matter to them. So I waited for the next commissioner, and then inexplicably they changed their mind and said, “You can go almost anywhere you want, but we’ll send you with a staff person.” So from 1998 to 2001, I had almost complete access. In 2003, as PA Press was about to send the book to the printer, DEP suddenly said, “We need to review the book.” I said, “No, it doesn’t work that way. You already gave me permission.” Based on his advice, I told DEP that they weren’t going to get to see anything, and eventually they backed down. Then, after the book was published, they bought 200 copies.

Four steps back, four steps forward—the bureaucratic dance.

This is what I know from working in city government. So then I started working on several other projects, but I thought that there was a lot of the water system that I hadn’t photographed. I thought I might come back to it. Eventually I started doing research and realized that there were hundreds of sites all around the city, just out in plain sight. So I walked the routes of the three water tunnels; each one has about 20-30 different shaft sites. There are 120 sewer pumping stations all over the city. There are wastewater treatment plants. There’s evidence of the old Croton Aqueduct. There’s this incredible block up around 153rd Street that has a diagonal slice right through it where the aqueduct used to go. It’s a community garden now. How many people know this? So the design for the new book is completely different. A printed map comes with the book, and there’s a link to a more detailed Google map which you can use as a field guide to go out and find many of the sites.

Dam and Spillway, Cross River Reservoir, Westchester County, 2000.

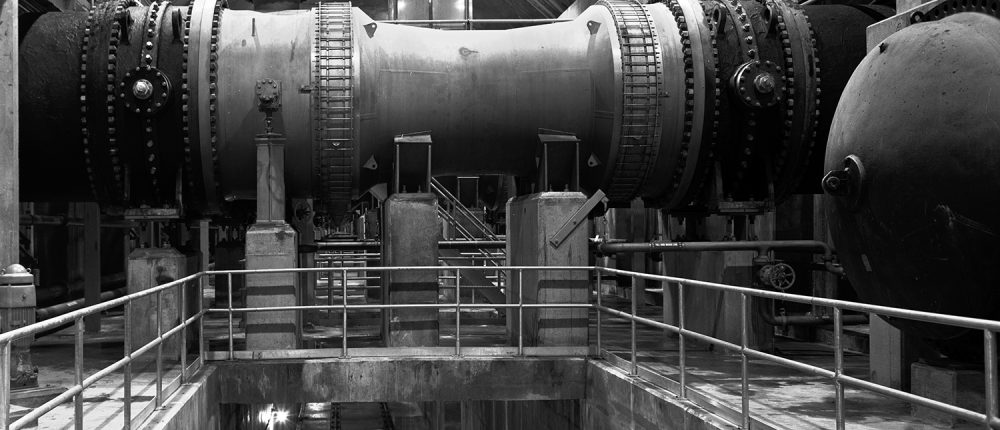

Jamaica Water Supply Pumping Station No. 22.

Do you think people will do that?

Thirteen thousand people have looked at the map since I posted it a couple months ago. I gave a talk at the Center for Brooklyn History, and 500 people signed up. So there is a lot of interest.

Walk me through your photographic process.

It’s different for every project, but it usually starts with seeing or reading about something interesting. Then I go out and look around, if I can, and go to the library or online, which is so much easier now. When I did the first book, everything was in the library. There was no real presence of water infrastructure information on the internet. But now there is, though it’s not always obvious where to find it. There are so many documents and records that may not be specifically about the water system, but the information is there. I found a big report done after Hurricane Sandy about upgrading the sewer pumping stations. It listed 80 of them, where they were, with pictures of them. I would have found that information eventually, but this made it so much easier. Occasionally I just see something that interests me, photograph it, and see where it goes. I don’t really have any rules for myself except that I usually make a map to track where I want to go and where I’ve been.

Once you get to the site, what do you do?

I was photographing at a physics lab, and someone there asked me if I knew in advance what I wanted to photograph. I said, “I always know exactly what I want to photograph before I get there, and I’m always wrong.” I usually have a pretty good idea of what I’ll find, but I’ve learned that the element of chance is my friend rather than my enemy. You just have to be ready for what comes up.

And what format do you shoot in?

The original book was done with a 4×5 view camera. The newer pictures, done on walks or bicycle—I actually bicycled the routes of the old Croton and the new Croton Aqueduct through Westchester—those are all done with a digital camera, usually a medium-format digital camera and sometimes a smaller format. There was actually one photograph of the interior of the gatehouse at the Central Park Reservoir where the door could be opened an inch. I slid my phone in to make that picture.

I understand your obsession with water infrastructure, because it’s really the reason New York is New York. The city was shaped by water, and the infrastructure is well over a century old and was kind of a miracle of 19th century engineering.

It was very forward thinking. It’s the reason that the city is the size it is. Before Brooklyn became part of New York City in 1898, it got its water from a series of wells and ponds along what is now the route of the Sunrise Highway. But it needed more water. They went to Suffolk County, did a lot of surveys, but the county eventually said, no, you can’t have our water. They looked in New Jersey, and they said no. They went to Rockland County and Rockland said, you can’t have it. So Brooklyn was in trouble. New York City had already started exploring getting water from the Catskills and had decided that that’s what they were going to do. And the people in Brooklyn realized, If we become part of New York City, we have access to that water. It’s one of the big reasons that the vote passed.

Featured image: Shaft-2b, City Tunnel No.3, Bronx, 1992. All photos courtesy of Stanley Greenberg.