The Atlanta We Inherit: History, Architecture, and the Fight for Public Space

Atlanta’s skyline tells a story of ambition, reinvention, and social exclusion. At the center of it stands architect-developer John Portman, whose master planning of the Peachtree Center district in the 1970s transformed the city’s downtown into a self-sufficient urban enclave. Portman didn’t just design buildings; he envisioned entire ecosystems of hotels, plazas, and atriums, all connected by skywalks that would allow people to navigate the city without ever touching the street.

Today, more than 20 skybridges and underground tunnels crisscross downtown Atlanta, not all designed by Portman, but following the typology he first introduced through Peachtree Center, with similar patterns appearing elsewhere across the region. In addition to keeping people off the street, this network enables prolonged stays within the complex for conferences, dining, and even traveling to the airport, all without directly experiencing the outside worldIn addition to keeping people off the street, they enable prolonged stays within Peachtree Center for conferences, dining, and even traveling to the airport—all without directly experiencing the outside world. Initially intended to enhance connectivity, this infrastructure has served to discourage urban interaction, siloing pedestrians from the vitality of street life and isolating them from fellow citizens.

Portman’s strikingly futuristic designs revitalized parts of Atlanta during a period of urban decline. But they also reinforced a fundamental divide between private and public space, prioritizing the needs of tourists and commuters over local residents. What once appeared as a vision of the future now feels insular and antagonistic to civic engagement.

Now, Atlanta has an opportunity to reclaim its skybridges. By drawing inspiration from Portman’s vision while learning from past mistakes, the city can transform these structures into tools for remembrance and reconnection. This approach would celebrate Atlanta’s architectural legacy while refocusing downtown on community needs and revitalizing the urban experience.

A performance-informed approach to downtown Atlanta invites people to see skybridges not as relics but as catalysts for connecting people, programs, and public life. This conceptual project examines the transformative potential of a skybridge adjacent to Marriott Marquis, which spans a parking lot. A ground-level mixed-use plaza is proposed to anchor the elevated structure in the public realm. This case study seeks to generate street-level vibrancy while honoring Portman’s visionary form-making, aiming not to erase the past, but to embrace it, transforming symbols of separation into features of a shared urban identity.

An aerial view of Atlanta (left), with skybridges mapped in red (right).

An aerial view of Atlanta (left), with skybridges mapped in red (right).

Recentering a City Shaped by Disconnection

Atlanta presents a unique urban landscape, one often described as formless, resembling an “O” with branches sprawling outward and converging into a singular looping highway known as “the Perimeter.” This ring emerged during the city’s expansion beyond downtown in the 1960s and 1970s, reflecting a lack of a definitive center or clear boundary. Instead, Atlanta is characterized by multiple fragmented centers, echoing the urban rhythm of Los Angeles. At times, and in various locations, the city pulsates with vibrancy, while at others, it seems to be a mere shadow of its potential.

During the 1970s, the traditional American concept of “downtown” teetered on collapse. From Manhattan to San Francisco, the cores of major cities fell into vivid and widely publicized decay: crime surged, infrastructure decayed, and tax bases crumbled, with “white flight” driving middle- and upper-class people out to the suburbs. Downtown was no longer the heart of the city; it was its wound. Atlanta, remarkably, defied this trend. While other cities hollowed out, it built upward, its skyline emerging as a symbol of urban renewal.

Learning From Portman: A Vision Without Isolation

Portman, who stood at the center of this transformation, was a hybrid figure, both architect and developer. He possessed the rare ability to realize ambitious ideas without waiting for approval. His legacy can be seen in the grandeur of Peachtree Center, the Marriott Marquis, and the skybridges that connect them. As historian Kevin Kruse observed, this model mirrored the broader suburbanization of Atlanta, reflecting and reinforcing white flight and economic stratification. Rem Koolhaas has noted that inward-facing architecture, once intended to save cities, often hastened their unraveling. Atlanta, always eager to frame itself as “the city too busy to hate,” accepted the tradeoff: civic life for climate control, memory for mobility.

While other U.S. cities—such as Denver, Detroit, and Pittsburgh—responded rapidly to the crises of climate and socioeconomic inequity, making significant investments in enhancing public spaces and transit connectivity, Atlanta’s downtown remains fragmented and stagnant. New York City’s High Line transformed a derelict rail line into a vibrant pedestrian corridor, weaving public life across Chelsea. Seoul’s Seoullo 7017 revitalized an overpass into a thriving walkway and biodiversity corridor, connecting previously isolated districts. These transformations address spatial injustice, turning unused infrastructure into democratic spaces that build on the past.

Kickstarting transformation

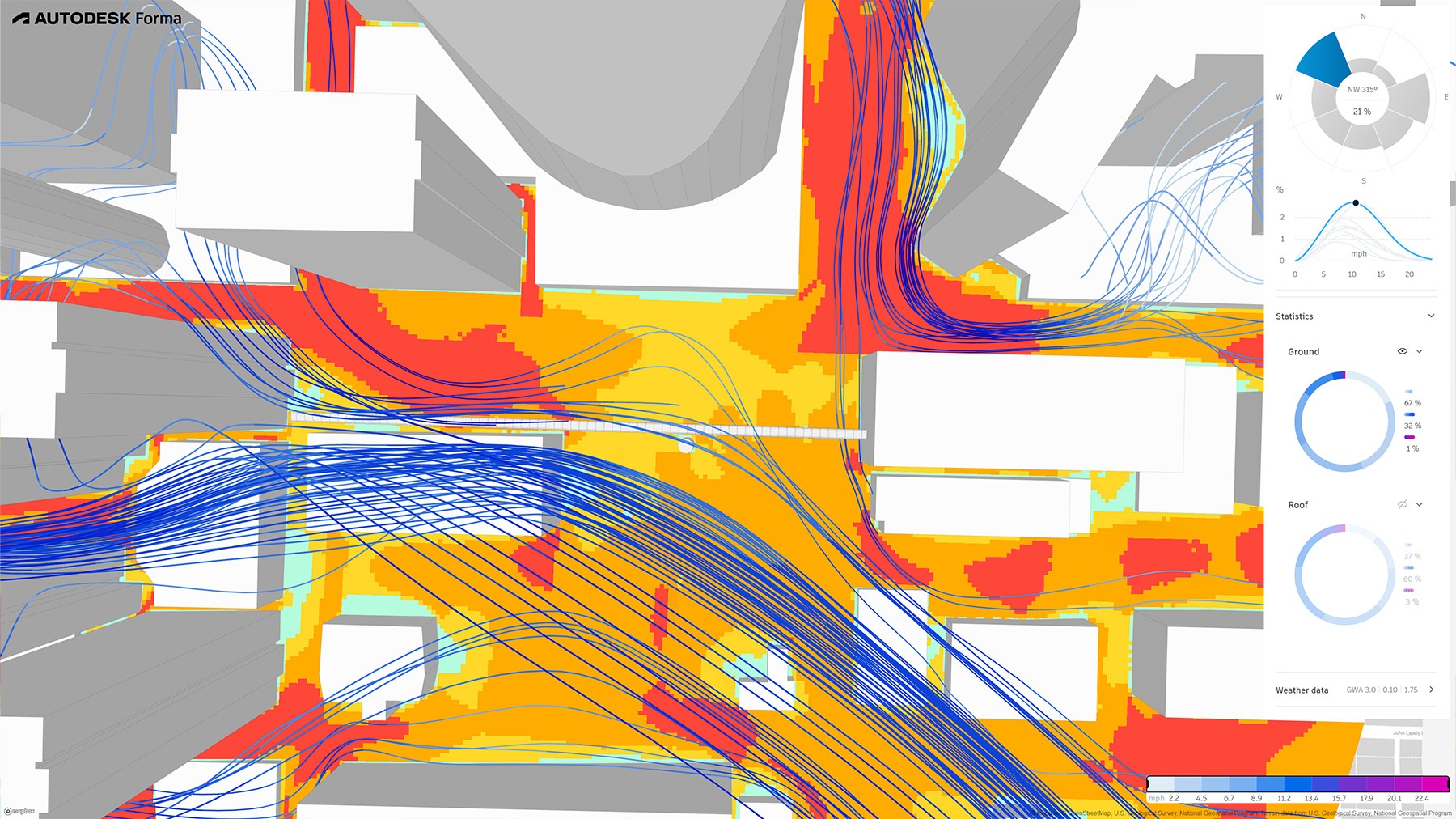

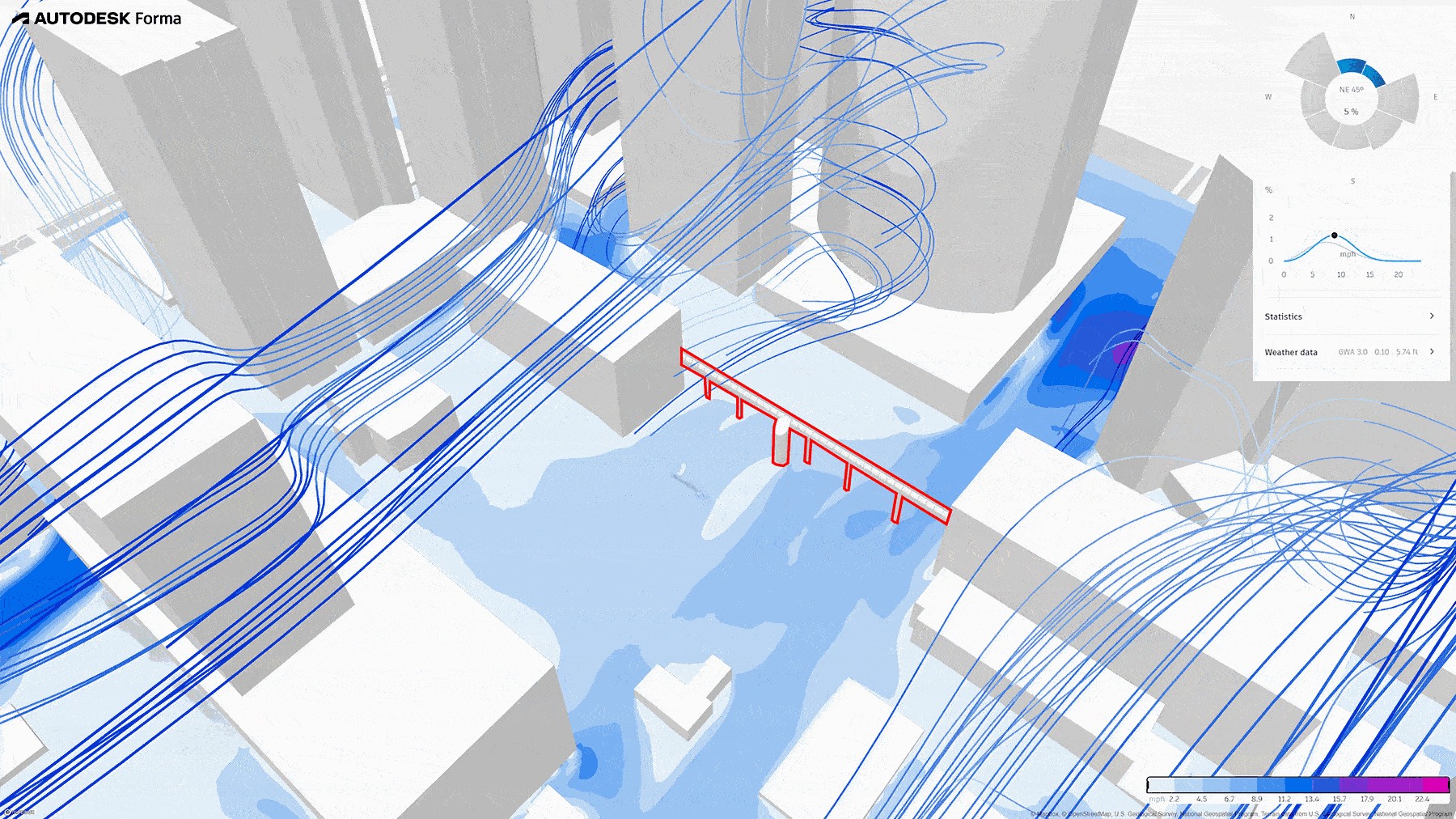

The skybridge at the center of this case study is at the intersection of John Portman Boulevard NE and Courtland Street NE. To explore its potential for transformation, a wind analysis simulation was conducted at the proposed intervention site directly in front of the Atlanta Marriott Marquis. This revealed highly active wind corridors funneling through the street-level canyon between towers, with consistent southern and northwesterly flows (up to 20-plus miles per hour in certain narrow passages). This overlooked environmental condition offers latent design potential.

Wind flow simulation revealing urban microclimate patterns around proposed structures.

Wind flow simulation revealing urban microclimate patterns around proposed structures.

Top: A wind comfort analysis with ground-level colors indicates pedestrian wind comfort. Image 4 Bottom: A wind speed analysis showing intensity, with shades of blue representing wind speed intensities (darker blue = higher speed); streamlines show wind flow patterns across the site.

Instead of fighting against the winds, a reimagined skybridge and stepped plaza could harness them, creating comfortable outdoor spaces, promoting passive cooling, and incorporating kinetic shading or sound-responsive features. Wind, often seen as a hindrance, here becomes a design element that enhances the atmosphere, influencing how people move and pause.

Wind is not the only weather element this case study accounts for. Ribs, or frames, are installed along the length of the skybridge to provide cover from sun and rain, heat and cold. Inspiration was drawn from Portman’s soaring atrium inside the Marriott Marquis, one of Atlanta’s (indeed, the nation’s) most striking interiors. As it is hidden from the outside, this case study reverses the current condition, exposing the structure and showcasing this architectural marvel to the city outside.

Left: Aerial view of proposed site for the skybridge case study at the intersection of John Portman Boulevard NE and Courtland Street NE. Right: The atrium inside the Portman-designed Marriott Marquis, whose architecture inspired the ribbed form of the skybridge.

Left: Aerial view of proposed site for the skybridge case study at the intersection of John Portman Boulevard NE and Courtland Street NE. Right: The atrium inside the Portman-designed Marriott Marquis, whose architecture inspired the ribbed form of the skybridge.

Reactivating Streets and Honoring the Past

At first glance, the skybridge in question may appear to be an unremarkable infrastructure. However, envisioning it as a public space focused on historical orientation and collective return completely transforms its significance. Here, the architectural form is not incidental: the structure includes a series of rotating ribs, or frames, each one aligned toward a historical site that no longer exists but continues to haunt the city.

One frame turns northeast to Oakland Cemetery, where “Slave Square” holds the remains of nearly 900 enslaved people buried with minimal markers from 1853 to the end of the Civil War. Another faces the five MARTA station, Kennys Ally, and Underground ATL, once home to the Crawford Frazier Negro Brokerage House, where enslaved people were auctioned. These gestures do not offer resolution but recognition, revealing what architecture often neglects in Atlanta: they indicate what has been erased.

Left: Proposed case study location in downtown Atlanta, aligned with the historical locations referenced by the ribs, or frames, of the redesigned skybridge. Right: Aerial overview highlighting how the skybridge ribs are oriented toward specific historic sites.

Left: Proposed case study location in downtown Atlanta, aligned with the historical locations referenced by the ribs, or frames, of the redesigned skybridge. Right: Aerial overview highlighting how the skybridge ribs are oriented toward specific historic sites.

Artist Paa Joe’s 2020 exhibition at the High Museum, Gates of No Return, highlighted these absences. His replicas of Ghanaian slave castles acted as portals, spatial elegies to lives rooted in violence and forgotten by space. The museum also featured a digital map showcasing lost or hidden slavery sites in Atlanta, unmarked on the skyline. Design can memorialize these places. Through orientation, framing, and cultural programming, this skybridge serves not just as a passage, but as a connection to the city’s past and a shared civic future.

Why Not Atlanta?

Atlanta has a rich history of transformative public investments that showcase the city’s commitment to bold and impactful changes. These initiatives not only reflect the legacy of public-backed investments but also serve as a model for future development, demonstrating the power of strategic interventions to enhance community life and stimulate growth. In the lead-up to the 1996 Olympics, Atlanta showcased its commitment to public development in remarkable ways. As a 1987 Atlanta Journal-Constitution article recounts, Mayor Maynard Jackson tasked his economic development chief, Richard Stogner, fresh off the successful delivery of Hartsfield-Jackson Airport, with reviving Underground Atlanta. Despite claiming to have “no money,” the city made it happen.

Of the $140 million invested (roughly $394 million today), an astonishing 61% came from city-backed bonds, with the remainder sourced from public loans (16%), grants (10%), private investment (11%), and other sources (2%). This wasn’t just a symbolic move; it was a strategic reinvestment in the city’s core.

By 1991, property tax revenues in Atlanta had risen from $134,000 in 1984 to $533,000, driven by the value of merchandise and fixtures among tenant businesses. Additional sales tax revenues brought in $209,000 that year. When combined with alcohol beverage taxes and license fees, the project generated $908,000 in additional tax benefits for the city in 1991 alone.

Beyond the fiscal return, the project spurred economic momentum and helped revitalize the south side of the central business district. It created approximately 3,000 new jobs and drew nearly 13 million visitors in its first year; strikingly, 60% of them were locals. Underground Atlanta became not only a cultural touchstone but also proof that bold, public-private investment could reactivate dormant urban spaces.

Catalytic assets such as Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the transformative Georgia State University campus, and the initial phase of The Stitch are already playing a pivotal role in shaping the future of Atlanta’s urban core. This presents an opportune moment to renew focus on commercial mixed-use projects that engage the public and revitalize existing infrastructure. Portman’s skybridges hold the potential for a reimagined future: one that emphasizes accessibility, creativity, and a strong sense of civic connection.

A More Inclusive Vision for Downtown

Considered on its own, design has limited impact. Throughout Atlanta’s past, present, and future proposals, many developments have overlooked a crucial fact: architecture that disregards history risks stripping away the very essence of a place. While some projects are dressed up in nostalgic aesthetics, few genuinely connect with the complex and often painful histories of their locations. As Destinee Filmore points out in her push for historic markers across the city, Atlanta’s Southern heritage is still tangible, woven into the fabric of downtown, which was once the heart of the region’s transportation systems. Mile Zero, the marker for the Western & Atlantic Railroad, stands as a quiet reminder of the city’s founding, yet too many people walk by without understanding its significance, or even knowing where to find it.

Too often, institutions create spaces that feel disconnected from their surroundings: they import styles, use sterile branding, and adopt cultural languages that ignore Atlanta’s rich diversity and physical identity. The city now stands at a pivotal moment in history, where a multiracial, post-segregation society is still grappling with what a shared public culture looks like. One common approach has been to remove controversial symbols from public life and confine them to museums or private homes. However, this binary solution offends both sides: for white Southerners, the Confederacy represents personal heritage and sacrifice, while for Black Southerners, the legacy of civil rights and the fight for racial equity carries equal cultural weight. Perhaps the more courageous path is to acknowledge both truths in public spaces, not as endorsements, but as evidence of a shared history that is still unfolding.

This case study doesn’t aim to erase Portman’s legacy but to confront it directly, while also honoring Atlanta’s overlooked history. Atlanta’s design future must emerge not from vertical isolation but from horizontal reconnection across streets, stories, and struggles. The opportunity lies not in building what already exists but in reprogramming its use, making room for new narratives and public culture.

This is where small design gestures, like rethinking a single skybridge, can become symbolic and functional acts of healing. This case study proposes a mixed-use civic intervention that reconnects the fragmented pedestrian network while opening space for cultural programming, historical memory, and shared ritual. Although the project’s timeline and scope may not allow for full historical reconciliation, it lays the groundwork for ongoing cultural engagement.

This is a call for infrastructure that doesn’t insulate wealth, but fosters community. A bridge that doesn’t separate individuals from history, but leads back to it. A street that doesn’t bypass memory, but insists on it. By breaking the bridge and stepping back down, there is a return not just to the street but to the essence of the community. This is how Atlanta heals: not through spectacle, but through presence. The next chapter of Atlanta’s built environment should not be a “city within a city” but a “city within its people.”

All images courtesy of Page, now Stantec.