The City of New Orleans and the Power of the Creative Economy

Carol Bebelle is the ultimate New Orleans “culture bearer.” A Crescent City native, a poet and essayist, an administrator and planner, Bebelle is also the cofounder of the Ashe Cultural Arts Center, an organization dedicated to using arts and culture as a tool for community redevelopment. In the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the center became a beacon for returning residents. Over the ensuing years, Ashe helped anchor a redevelopment of Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in Central City that felt more authentically place- and culture-driven than many of the post-storm efforts in the city.

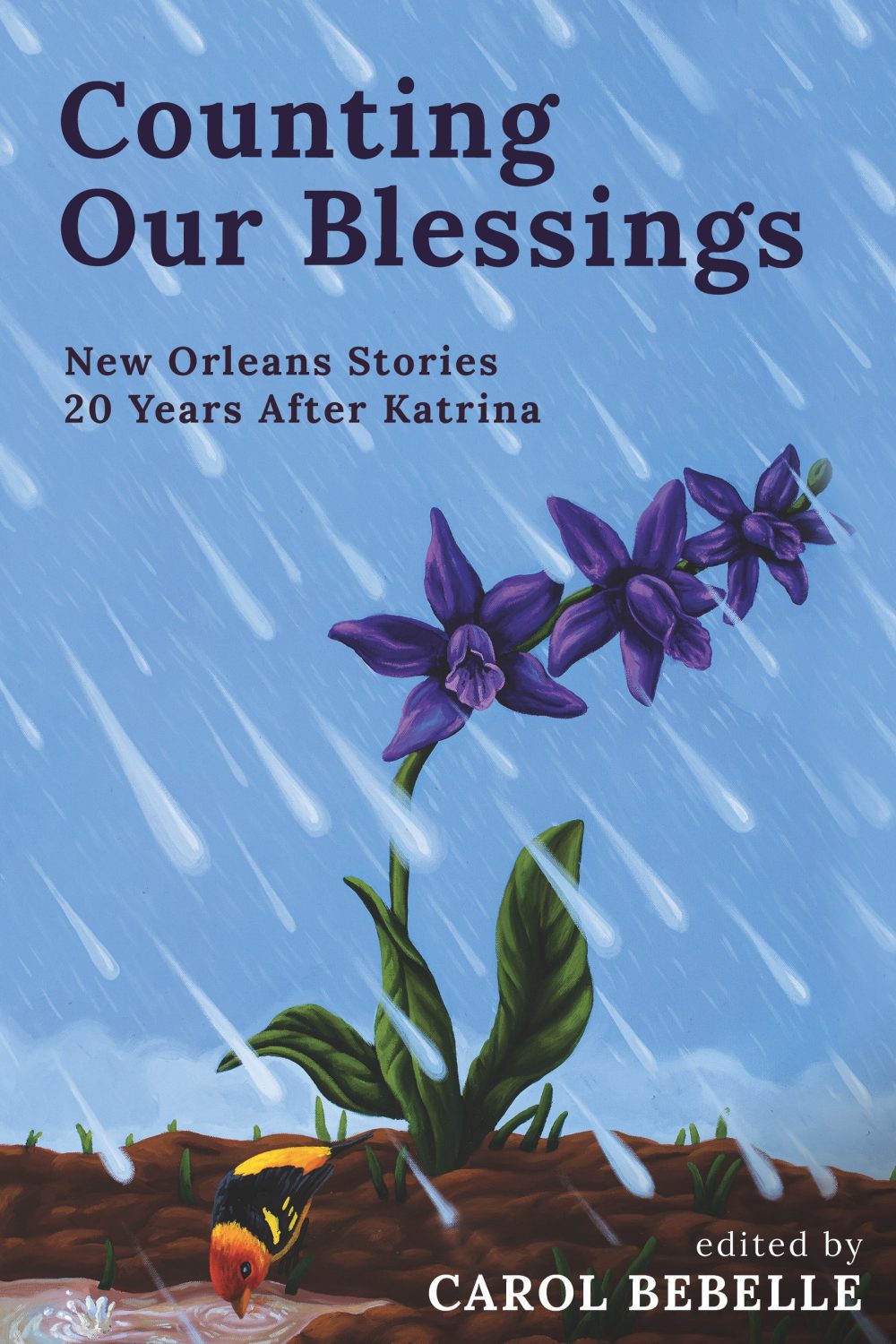

For the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, it is altogether fitting that Bebelle has compiled an impressive volume of stories giving testimony to both triumph and tragedy, light and dark. Counting Our Blessings: New Orleans Stories Twenty Years After Katrina (University of New Orleans Press) is a journey through the lives of 41 New Orleanians (including Common Edge co-founder Steven Bingler) in the aftermath of the great storm. Recently I talked to Bebelle about the inspiration for the book, the city’s new mayor, and why the cultural economy of New Orleans remains vitally important.

MCP: Martin C. Pedersen

CB: Carol Bebelle

Tell me the origin story of Counting Your Blessings.

It starts, of course, with Katrina. Being a lifelong resident and the cofounder of a community-based cultural arts center, there were a lot of things happening when we wound up evacuating for the storm. But we were extremely lucky. We got back earlier than most, in six weeks. So then the question became, What should we do? Clearly, whatever our mission was previously was now secondary to how we could be useful in assisting people in the wake of this horrific event. Within weeks of our return, we discovered that we had become a beacon. Because we were here early, there were not many organizations on the ground, so we became the place that people could bring or direct resources to. This forced me to look both at the terrible thing that had happened, but also the good that was coming out of it. So the idea of being able to recognize both the darkness and the light started for me then.

I moved to New Orleans in 2011. We were the second wave of people post-Katrina, and one of the things I would do was ask people their “Katrina story,” and everybody had one. There were commonalities, but everybody had their own, which were moving, interesting, and uplifting.

Yes, absolutely. The story that compelled me to do the book came from my friend Mary. I ran into her one day—it had to be a year after the storm—and we got to talking and were still in that period where you asked, “How are you doing?” and you could be there for an hour, getting the answer. She told this story about her and her husband, Alex. When they left, they went to Texas, where her pregnant daughter lived. After the storm, Mary had not had the capacity to come back, so Alex had to carry that whole burden by himself, coming back, cleaning out the house by himself.

They had a ritual. He would leave on the weekends, and they would call back and forth. On this particular weekend, they got off schedule. She didn’t care because she was running around with her daughter, who was close to delivery. Mary was lamenting the fact that this was going to be the first child in her family’s history for a hundred years not to be christened in the family christening gown. At one point she runs into a country store, and they’ve got an apron sale, which reminds her of Big Mama’s apron. So she calls Alex and says, “While you’re looking for the christening gown, look for Big Mama’s apron.” Finally, they get home. It gets later than usual. She hasn’t heard from Alex. The phone rings. It’s from his phone, but his voice doesn’t sound right, then the phone disconnects. She calls back and discovers that he’s in a moment of deep emotion. “What’s the matter?” she asks. “I found the christening gown,” he says. “Oh my God, where?” He said, “It was right by Big Mama’s apron.” That story really got me thinking about the things that were found in the storm.

Great story.

But as time went on, I kept hearing more stories. Folks who hadn’t talked to each other in forever, family members, who wound up having to live together for a month or two. The elders who got together and forced reconciliations. Things like that, as well as the strangers stepping up. We wound up working with Eve Ensler in the creation of a theater piece called Swimming Upstream. There was a monologue in that piece called “You Came Through,” and it was about all of the stories of how people paid for folks’ groceries, did all kinds of things to contribute, not to mention all of the people that came down here to help.

People ask two questions: What were the lessons of Katrina, and then who saved New Orleans? New Orleans was saved by the people of New Orleans. Not by the mayor, the president, or by senators.

By the people of New Orleans, and our fellow Americans. I sat next to a woman on a plane who told me a great story. On that late August weekend in 2005, her family woke up to hear about the levee break. Everybody stayed in their pajamas. The kids continued to play, and her husband just sat in the bed, startled. Before they knew it, it was nighttime. They sent the kids to bed. The next morning, he got up early. She thought he was getting the kids ready for school, and he was, but he had suitcases on the floor, and she said, “What’s going on?” He said, “I can’t watch this anymore. I called the office and told them I’m going to be out of the office for a couple of weeks, and I am going down there to see what I can do.” I heard many stories similar to that. So I just felt a responsibility to give a report from the light, because that’s what I consider this book to be.

Twenty years have now passed. What’s changed about the city? What’s endured?

Well, I think that what has endured is the culture. That has not changed. That was the same 20 years ago. What’s different is that the influence of culture is being diluted by people who are bothered by the culture, because it’s unsettling. If you’re ill-accustomed to the power of human presence, having lots of it around you can throw you off.

Well, Americans in general live mostly suburban lives in their cars, so that urban intimacy is foreign to them.

I’m 76 now, and I grew up in it. I still feel like this is New Orleans, and in the times that we’re living in now we really need the model up and operating so that people can see what’s different and better about being closer rather than being separated. And so we have to hold on to our culture, but it’s a day-to-day battle. We’ve got to be attentive to the culture. We’ve got to treat it like a garden that has to always be nurtured.

Photo by Antwamesha Jenkins.

Are you optimistic about the new mayor?

Mayor-Elect [Helena] Moreno had done some great work in terms of getting people from different communities behind her. If she’s able to attend to the needs of the various communities that supported her, then she will indeed be a great mayor. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Getting elected is only one part of the equation. In fact, it’s the part of the work that’s the least needed after you get elected.

It’s the fun part for politicians to run around, shake hands, and kiss babies, but then you’ve got to run the machine.

Oh, yeah, you got to run a city that’s broke, a city that’s got economic issues. People love to talk about the streets. I keep saying, “Guys, what happens after the streets get fixed?” Our education system still needs some attention. We need to make it possible for all of the creativity that we have in the city to be collected in ways so that folks can be doing the work they love. We have people here who love the culture. They love everything from beading to second lining, to making music, to making theater. But one of the things I miss right now is artwork that’s about the potential for a just world. We spend a lot of time as artists talking about how we got into the bad shape we’re in now, and we’ve taken that and projected what this bad shape could mean for us for the future. It’s just as important, even if people consider it fantasy, to imagine a different world. If we made it possible for people to have life, liberty, and be pursuing happiness? What would that look like on any given day? So the cultural economy needs a greater investment. Maslow told us a long time ago: food, clothing, shelter, and then belonging. And belonging is the absolute center of culture. We’re in a city where the cultural economy is productive enough to fill up all of these hotels and restaurants, but we’ve been starving the golden goose. If the golden goose can do all that while starving, what could it do if it was fed?

Featured image by salin1 via Flickr.