A Requiem for MIT’s Room 10-485

Room 10-485 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) sits directly beneath the university’s great masonry dome, which overlooks Killian Court and the Charles River. Tucked high in the Maclaurin Building (Building 10) like an attic, it has always felt a bit removed from the main Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) headquarters in Building 7, on Massachusetts Avenue. This sense of seclusion gives it a distinctive atmosphere: quiet, reflective, and full of creative energy. For many years it has housed the City Design and Development (CDD) group, where ideas about urban form, public space, and community design have been explored.

When I arrived in the fall of 1988, the room felt like a messy artist’s studio, a work in progress. Bare concrete walls, painted white, and exposed timber beams gave it a raw, unfinished quality. A large arched window flooded the space with light, revealing every imperfection and charm. The creaky mezzanine, made of rough wood, housed the CDD professors (at the time): Mark Schuster, Julian Beinart, Dennis Frenchman, and Larry Vale, while Gary Hack sat just below, in the mezzanine’s shadow. The whole place felt improvised, as if constantly under construction. On the other side of the room, rows of student desks were separated by low wooden partitions, creating a kind of communal workshop. Here, my ideas about cities took shape amid all the clutter.

As a Latino from East Los Angeles. I felt surprisingly at home in this DIY—or rasquache, as we say in Spanish—space. Its imperfections allowed me to be imperfect, too, and carve out a small corner of belonging, both physically and mentally.

For me, Room 10-485 was more than just a workspace; it was a refuge during my early days studying city planning. I struggled with reading and writing at the time and felt unprepared for the rigor of my three-year program, which combined a Master in City Planning and a Master of Science in Architecture Studies. Though intellectually rich, the DUSP curriculum often stripped the joy from cities, reducing them to data points, rational models, and conflict-driven debates. Much of that work was important, yet I sensed there were limits to understanding urban life through analysis alone. Without the vocabulary or confidence to argue that point, I turned instead to what I knew best: my gut feeling for place and my childhood habit of building small model cities.

Hack often spoke about the “good city” and the “bad city,” and about the role of the boulevardier, the urban observer who experiences the city by walking through it. His discussions made me think deeply about East Los Angeles, where I grew up. Was it a good or in a bad place? The answer depended on how one looked at it: through numbers and planning metrics, or through the physical senses and lived experience.

I found myself drawn to the latter, shying away from data, policy, and formal urban design. In spirit, I joined the ranks of J.B. Jackson, Kevin Lynch, Grady Clay, Holly White, and Jane Jacobs, thinkers who sought to define urban space through observation, memory, perception, and everyday life. That perspective guided my own research into how Latinos shape and use space in East Los Angeles.

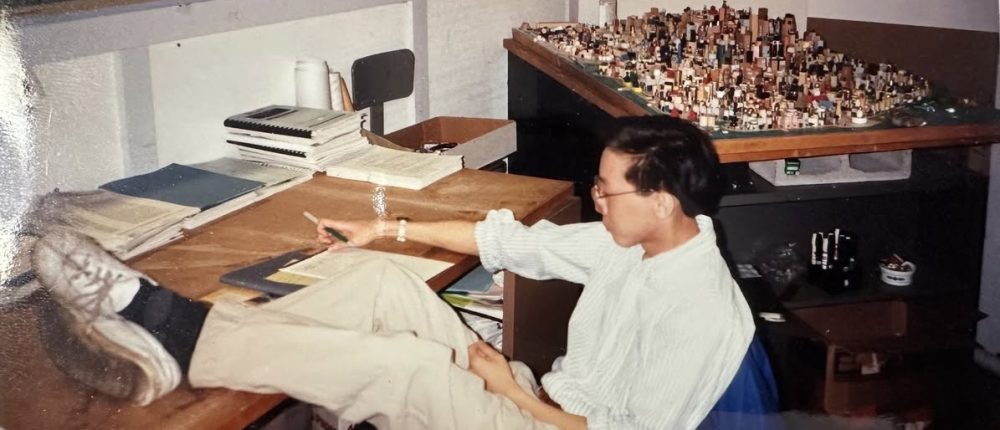

While my idea of Latino urbanism began in Room 10-485 more than three decades ago, I also began something there that continues to sustain my career today: I turned my studio desk, and those around it, into a three-year city-building marathon, spending countless hours late into the night experimenting with new ways to visualize the urban theories I was learning. As I struggled to master MIT’s technical planning language, model-building kept me grounded and at peace.

Those hand-built models were crude assemblages of found objects, scraps, nuts and bolts, buttons, and fragments that I arranged on a roughly drawn street grid and transformed into cityscapes. Like a flâneur of the imagination, I would quietly invite others to peek at my secret, sensory-based city. It intrigued them, though they never quite knew what to make of it. Was it child’s play, art, or a tool for planning? In the hyper-rational world of MIT, it felt like an illicit thing, an act of joy and imagination smuggled into a place that prized logic, numbers, and argument above all else.

A few years after graduation, I returned to Room 10-485 and found it completely transformed. The space had been redesigned, scrubbed clean of all imperfections. Keypad locks guarded the door. Computers now lined the walls, and the nooks and crannies where I once built my “secret city” were gone. There was no longer a place to squirrel away and create because every corner was accounted for. CDD had moved in a new direction, embracing the intellectual and cultural shifts within planning itself, leaving little room for improvisation or for thinking about space from a human, sensory perspective.

Today, Room 10-485’s days are numbered. When I recently spoke with Professor Larry Vale, who arrived there when I did and never left, he told me the entire planning department will soon move across Massachusetts Avenue. Generations of urban planning students, myself among them, who were shaped by that room’s spirit and faculty will fade into memory.

The physical space that once nurtured experimentation and imagination will become something else, but its ethos—that messy, creative, human way of understanding cities—endures in the work of those who passed through it.

In many ways, my career in urban planning has carried the ethos of Room 10-485, a place where I thrived amid creative disorder, constant experimentation, and unfinished work. Like that space, my journey has remained a work in progress, guided by curiosity, imperfection, and the belief that cities are best understood through the senses and the stories of the people who inhabit them.

Featured image: Buckley Yung recently posted a photo of the old MIT graduate studio in Room 10-485. Photo courtesy of Yung.