A Student Design Competition Tackles Forced Labor in the Construction Industry

Design competitions for both architecture students and professionals tend to focus on visual punch. Having served on hundreds of competition juries over the years, from local awards to international programs, I find they often run the risk of turning into beauty pageants. As presentation techniques become more sophisticated, so does the emphasis on image.

Thankfully, that’s not the focus of a new student awards program created by the Grace Farms Foundation and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA): “Design for Freedom Competition: Ethical and Equitable Materiality to End Forced Labor,” launched in spring 2025. While the title is a mouthful, the competition’s focus and the winners selected reflect the deep focus of the Design for Freedom (DFF) initiative to raise awareness of and end the pervasive use of modern-day slave and child labor around the world in the extraction of natural resources, the production of construction materials and systems, and in construction itself. According to DFF, 28 million people worldwide are held in servitude for forced labor. The organization has created tools to aid architects, designers, and the next generation of AEC professionals in ending such practices.

A little background: the DFF effort was created in 2020 by Grace Farms Foundation CEO/Founder Sharon Prince to understand the pervasive use of forced labor in the built environment. The following year, Prince gave a spirited talk at the University of Hartford, where I teach, which prompted me to write about DFF for Common Edge. An invitation followed to join DFF’s Working Group—a collection of 100-plus people from throughout the AEC industry working to raise awareness and develop design tools to help professionals make more informed decisions about specifying materials without the taint of forced labor.

I had just served on ACSA’s annual steel design student competition, so I suggested to Prince and the group that a student competition focused on Design for Freedom might go a long way to raise awareness among architecture students and faculty of the DFF initiative. The Working Group and DFF staff, along with helpful folks at ACSA, labored for a year to formalize and draft the competition details. The result was a two-pronged student competition: one focused on studio projects designed to use materials produced with minimal forced labor; the other concentrated on materials research to realize DFF goals. The debut competition commenced last spring, with some $18,000 in cash prizes to be shared by students and faculty. There were 65 entries representing 333 students and faculty, a robust number for a new competition. I was among the nine competition jurors from the DFF Working Group that selected the 10 winning projects.

During the jury process, it became immediately apparent that these studio projects and materials research efforts were focused primarily on the process of making architecture, not only just the finished product. Students and their faculty advisers took great pains to document alternative material sources with supply chains that were “clean” of forced or child labor. A key strategy was to use supply chains that were relatively short and mostly local, avoiding international material sources suspected of exploitative labor practices. Material salvage and recycling—much of it from nearby suppliers—was a key factor in keeping supply chains short and clean.

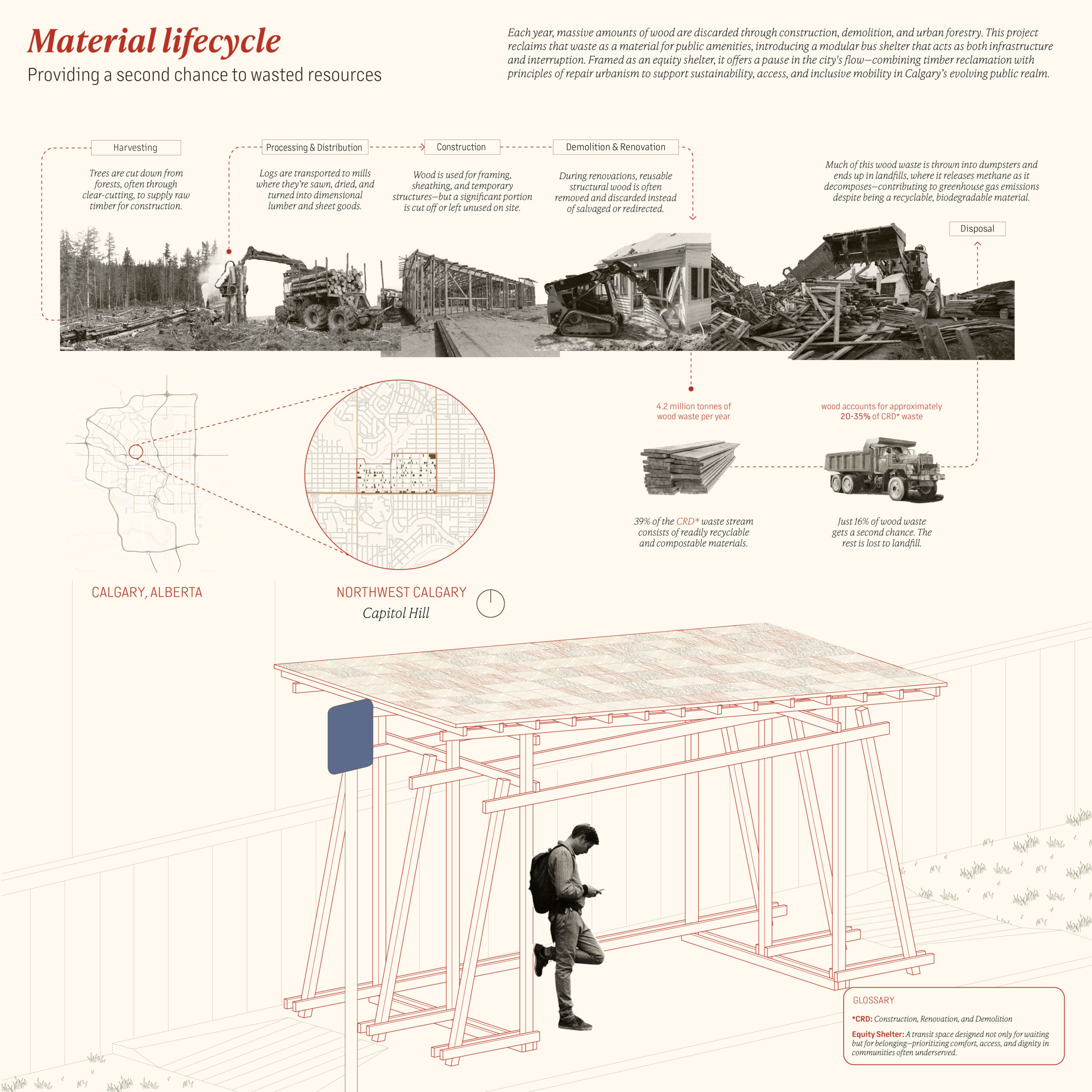

“Patches in Waiting: A Shelter for Equity and Material Justice,” by University of Calgary student Leonor Aguero Vivas (with Jessie Andjelic, faculty), partners with local renovation contractors to recycle wood waste.

“Patches in Waiting: A Shelter for Equity and Material Justice,” by University of Calgary student Leonor Aguero Vivas (with Jessie Andjelic, faculty), partners with local renovation contractors to recycle wood waste.

An example of a modest yet powerful winning design project is “Patches in Waiting: A Shelter for Equity and Material Justice,” by University of Calgary student Leonor Aguero Vivas (with Jessie Andjelic, faculty). Calgary has lots of wood waste from a plethora of residential renovations, along with a dearth of bus stop shelters. To create new ones, the project enfranchises local building contractors to collect and tag demo waste for recycling into shelters (approximately 40% of wood waste can be recycled in this way, avoiding landfills). It’s a simple concept, but one with great potential for larger-scale construction projects as well.

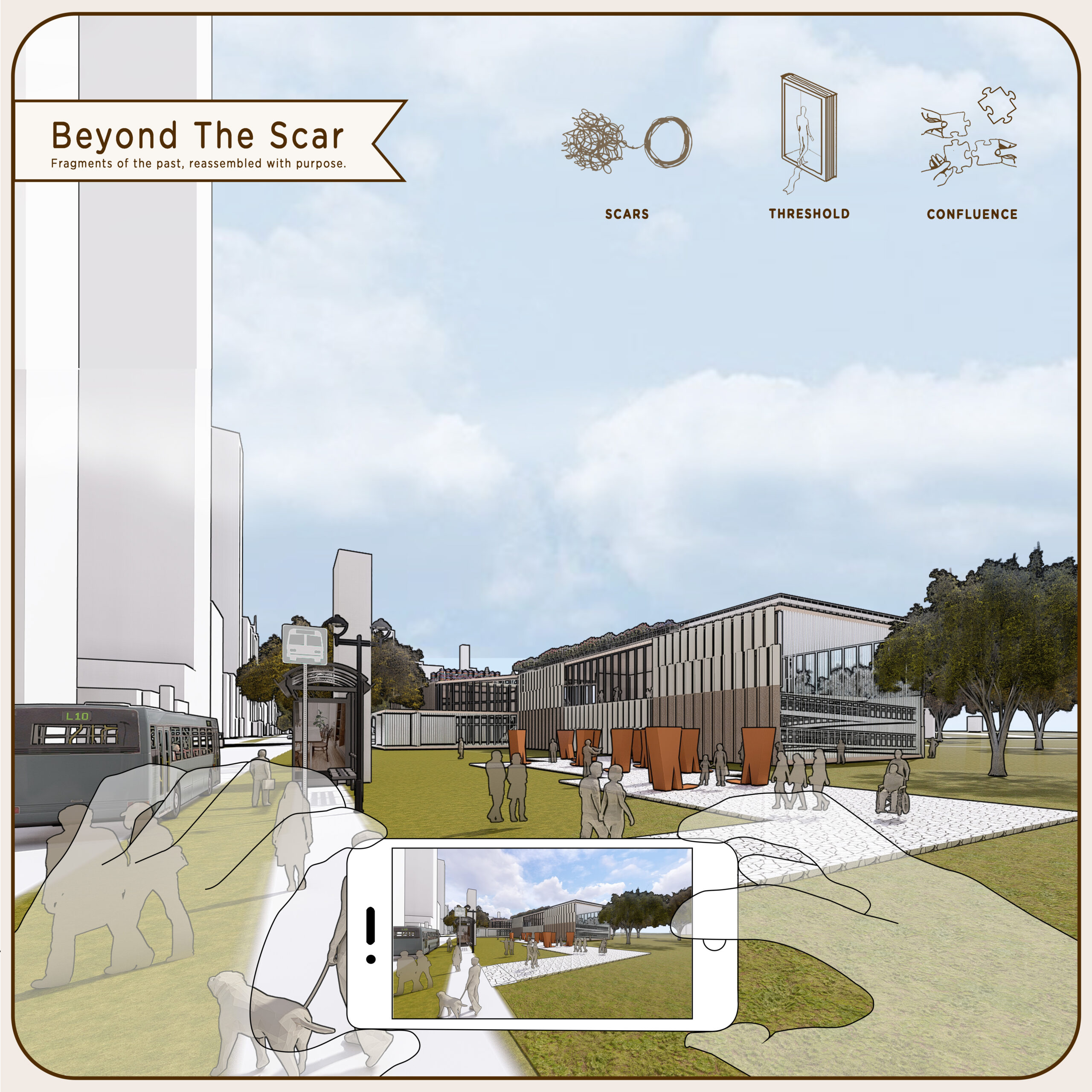

“Peace Museum: Beyond the Scars,” by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign students Nidhi Naik and Shamita Shyam Honawar (with Patricia Saldaña Natke and Soumya Dasgupta, faculty), employs recycled materials from Chicago neighborhoods to express the city’s wounds and ultimate rebirth.

“Peace Museum: Beyond the Scars,” by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign students Nidhi Naik and Shamita Shyam Honawar (with Patricia Saldaña Natke and Soumya Dasgupta, faculty), employs recycled materials from Chicago neighborhoods to express the city’s wounds and ultimate rebirth.

Another winner, “Peace Museum: Beyond the Scars,” set in Chicago, employs recycled materials as part of its exhibition content. Salvaged from some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, such materials suggest the scars from years of neglect, according to University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign students Nidhi Naik and Shamita Shyam Honawar (with Patricia Saldaña Natke and Soumya Dasgupta, faculty). The recycled materials throughout the design, explains the project’s copy, “reflect the city’s wounds—crime, displacement, inequality—while also bearing witness to its tenacity and spirit of rebuilding.” The jurors lauded this first-place-winning design project for placing “ethical material sourcing and labor equity at the heart of the architectural design.”

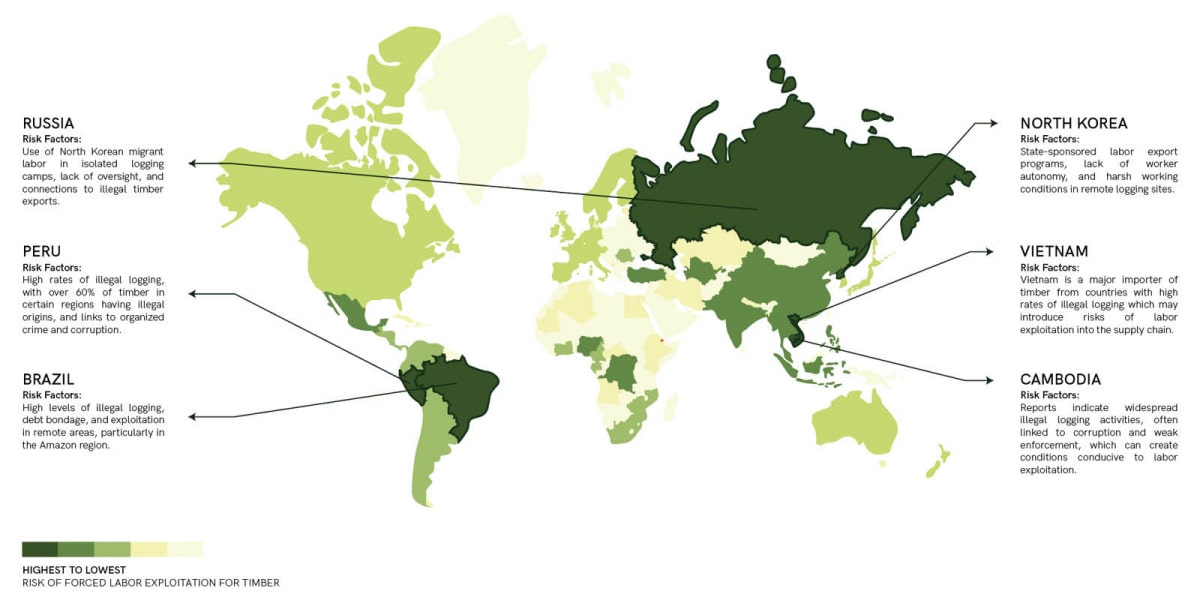

“Unmasking Greenwashing: Creating an Ethical Material Supply Chain,” by University of Southern California students Natalie Darakjian, Noelle Osborne, and Reed Wilson (with Takako Tajima, faculty), highlights hot spots for labor exploitation in the global timber industry.

“Unmasking Greenwashing: Creating an Ethical Material Supply Chain,” by University of Southern California students Natalie Darakjian, Noelle Osborne, and Reed Wilson (with Takako Tajima, faculty), highlights hot spots for labor exploitation in the global timber industry.

The first-place material research project, “Unmasking Greenwashing: Creating an Ethical Material Supply Chain,” takes a major step to address shortcomings of LEED and the Forest Stewardship Council in certifying timber. University of Southern California students Natalie Darakjian, Noelle Osborne, and Reed Wilson (with Takako Tajima, faculty), discovered that these commonly used standards inadequately track critical information such as the material’s country of origin or labor regulations. To provide full transparency, the project proposes using existing AI tools to identify key risk regions for forced labor in the production of timber, and marries that information with updated LEED standards though a new app, the Timber Ethics Tracker, that “uses research-backed insights from identified high-risk regions to expose gaps in LEED and create solutions that are designed with dignity.” The jury praised this research project for its “bold and forward-thinking approach, offering a well-researched and clearly presented tool designed to support practitioners in making more informed material and supplier decisions.” It’s a scalable tool that could have applications across the AEC industry.

We live in a world where empathy appears to be in short supply. But empathy is one of the essential qualities of great architecture: care not only for the people who live, work, and play within it, but also care for the people across the globe who create the materials and exert the labor to make architecture a reality. “Design for Freedom” is helping cultivate new generations of architects and designers motivated by care, and helping create architecture that locates empathy at its very heart. The projects profiled here give just a taste of the creativity and sophistication of this new competition’s winning projects.

For more information on all 10, visit ACSA’s website.

Featured image: “Nomadic Walls,” by Carnegie Mellon University students Ishika Dinesh and Yifan Feng (with Jongwan Kwon, faculty).