Lessons From Katrina: The Next Planning Frontier Is Community Empowerment

On the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, my mind rambles from the storm’s dreadful memories to some of the most valuable lessons learned. One of those lessons relates to the powerful forces that become available when communities are willing to band together and take control of their collective destiny. While this may in fact be the north star of most democratic societies, there are often too many things that prevent honest forms of democratic decision-making from occurring.

I remember my high school civics teacher opening the first day of class with a reminder that the United States of America is not a democracy but rather a democratic republic, where elected representation (some of us are smarter than all of us) and participatory democracy (all of us are smarter than any of us) exist in a complex power dynamic that is always struggling to maintain a healthy equilibrium.

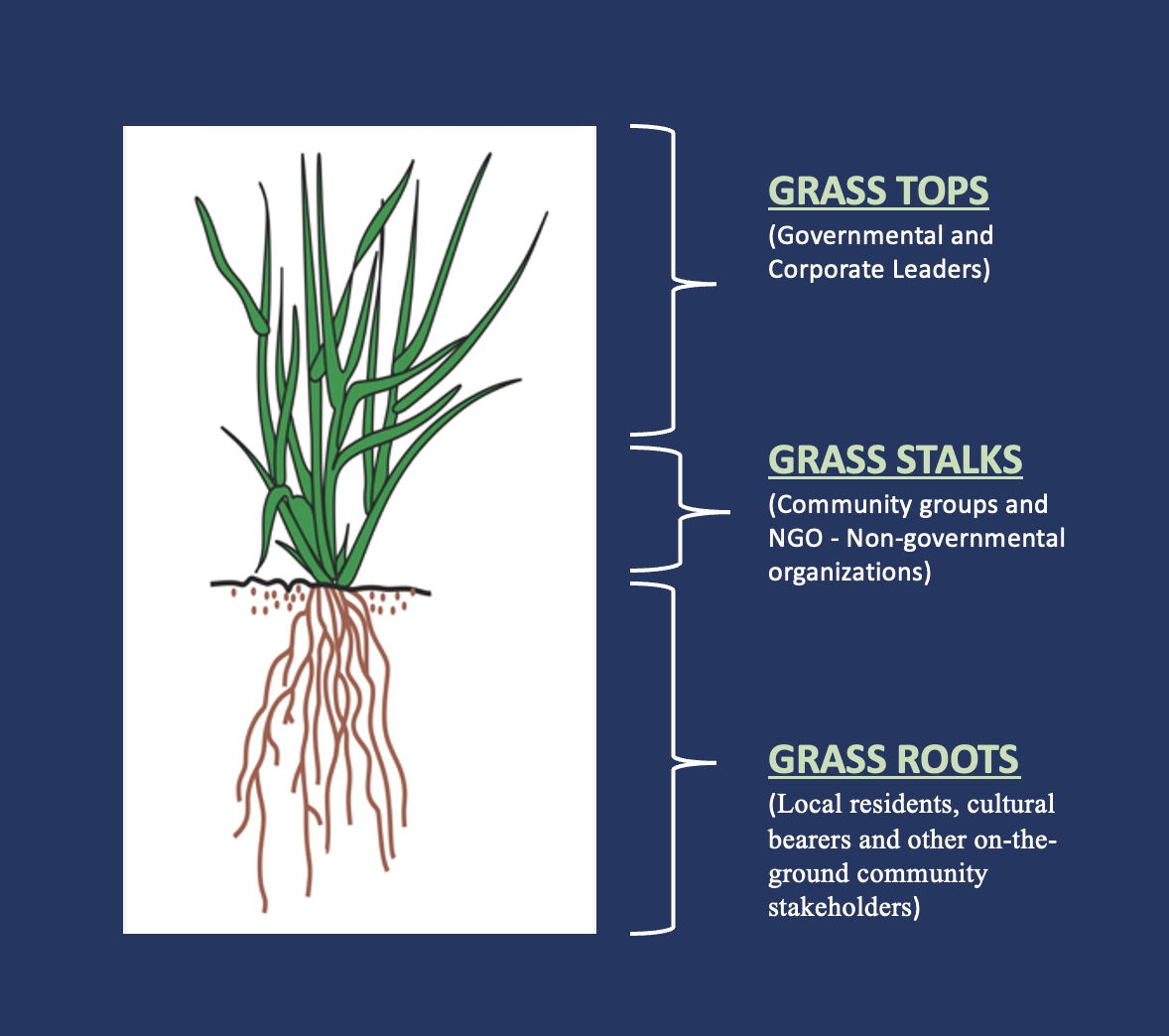

The metaphor I now use to describe the layers of leadership that combine to support these complex, fragile, and often contradictory ideals is a twig of grass. The upper layer of the twig contains the “grass tops” of representative political and corporate leadership. At the bottom of the twig are the individual residents and citizens who embody the “grass roots” layer of community leadership. In between is the “grass stalks” layer of nonprofit community organizations that deliver a wide range of support services related to social wellbeing, healthcare, even affordable housing. The quality of community life works best when all three layers of the ecosystem come together through an authentic decision-making process.

How this decision-making process is realized can take different forms. The simplest of these is called community participation, which is often delivered through public hearings, where planners and designers present predetermined solutions to stakeholders, who are free to give brief responses. This can lead to misunderstandings or, even worse, to co-option by top-down players looking for a rubber stamp on decisions previously made behind closed doors.

At the other end of the spectrum is a more robust community engagement model, often referred to as “codesign.” (Note that the dictionary defines engagement as “an emotional commitment to being involved with something.”) Here, skilled community planning facilitators lead a process in which design decisions are shaped by the people who will actually live with them every day.

A newer and more democratic frontier of community participation and engagement is community empowerment. Here, the dictionary definition becomes more direct: “the power, right or authority to do something; agency, the process of gaining freedom and power to do what you want or to control what happens to you.”

The complex dynamics of community empowerment are especially critical whenever there is risk or uncertainty, like after a catastrophic event, when outcomes can be life-altering, even life-threatening. After Hurricane Katrina slammed New Orleans in late August 2005, a quagmire of leadership caused the recovery planning process to be strung out for more than a year. The first phase, which emanated from the grass tops leaders in the mayor’s office, was ceremoniously rejected by the community, because the decisions made did not authentically represent the needs of local stakeholders.

The second planning phase was led by grass tops leaders on the City Council but rejected by the even more grass tops Louisiana Recovery Authority for its racially and divisively constricted scope. A third recovery plan, called the Unified New Orleans Plan (often referred to as the “people’s recovery plan”) was hatched by grass stalks leaders at the Greater New Orleans Foundation. This time, the community planning and design process included the voices of more than 9,000 citizens in 53 transparent neighborhood and community-wide meetings where residents could openly offer and monitor the flow of creative ideas. The outcome of this experience led to the generation of ideas and actions at an even more expansive scale, and a level of community empowerment by actual people expediting real change. Many of these efforts continue to this day.

In the early aftermath of the storm, Denise and Doug Thornton, residents of the suburban Lakewood South neighborhood, established a group of “Beacon of Hope” tool-lending sites where residents were free to borrow the hammers, saws, wrecking bars, and other equipment needed to gut and repair their own homes. On the other side of town, a group of local music enthusiasts teamed up with hometown heroes Branford Marsalis and Harry Connick Jr. and Habitat for Humanity to create Musician’s Village, a development with 72 privately funded single family homes and 10 elder-friendly duplex units of affordable housing, with the aim of encouraging local musicians to return home to New Orleans after the hurricane. A centerpiece of the project, the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music, houses performance spaces and practice studios and offers music education.

In the predominantly Black neighborhood of Central City, it was Carol Bebelle, a local resident and cofounder of the Ashe Cultural Arts Center, who was empowered to lead the development of a Main Street program for the complete redesign and redevelopment of the community’s historic Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard. At the same time, the Ashe Cultural Arts Center was busy fundraising, renovating and expanding its visual and performing arts spaces to accommodate its expanding community arts programs.

Another project sprang up from grass roots residents in the Lower Ninth Ward. Based on visions of the proverb of sankofa—a word in the Twi language of Ghana meaning, essentially, “to retrieve”—the Sankofa Community Redevelopment Foundation, under the leadership of its resident-director Rashida Ferdinand, opened a makeshift farmers market to address the community’s emergency food insecurities. Two decades later, the Sankofa Farmers Market is still going strong. The foundation has also not only created a quality-of-life neighborhood plan and institutionalized the market, but also developed a 40-acre wetlands park and nature trail to help secure the community’s long-range flood protection, enhance environmental education, boost community revitalization and economic development, and offer recreation for all.

The impact of organized community empowerment was also evident in 2024 after Mayor Latoya Cantrell announced plans to convert New Orleans’ historic Municipal Auditorium into a new City Hall. In response, local advocates for the future of the adjacent Louis Armstrong Park joined forces with 26 other community-based organizations to form a new community collective known as Save Our Souls to stop the project. The final blow was cast when community-empowered culturebearers teamed up for a “second line” drumming and dancing march on City Hall, after which the mayor was forced to withdraw her controversial development proposal.

These same empowering principles can happen anywhere. St. Petersburg, Florida, is home to the Historic Gas Plant District neighborhood. The area previously served as home to both Black and Native American communities—whose origins date back more than 8,500 years. In the 1970s, 86 acres of this history was sliced up by interstate highways and erased in 1990 by the construction of the massive Florida Suncoast Dome. From 1996 to 2025, the site was known as Tropicana Field, home to the Tampa Bay Rays baseball team. Recently, St. Petersburg’s City Council decided to terminate its agreement with the team and look at other options, including a replacement of the stadium with a new convention center.

This opportunity caught the attention of The Connection Partners, a group of community thought leaders whose vision is to foster “an environmentally sustainable, spiritually fulfilling, and socially just human presence on Earth.” Several members, including its founder, Sharon Joy Kleitsch, began with Zoom listening sessions that produced a slew of site programming possibilities: 2,000–3,000 units of affordable and mixed-income housing; a community-scaled conference center and conference hotel; a health center; community gardens inspired by local master gardeners Emanuel Roux, Carla Bristol, and Bill Bilodeau; a regional “living systems” research and economic development engine grounded in permaculture and food production; and an expansion of the existing Booker Creek watershed into a new 15-acre urban forest with an “ancestors grove” to celebrate the historical line of Indigenous and Afro-centric occupants who have called the place home. The group is now working to create a detailed master plan to back up its vision for the site. Whatever emerges from this process will stand as a testament to a community that is not just empowered, but emboldened to reimagine its future.

The evolution of community engagement to the more robust level of empowerment is the next logical and necessary step in the development of a more honest and authentically democratic form of planning and decision making. Learning from the lessons of Katrina, our nation’s mayors, supervisors, councilmembers, civic leaders, CEOs, and activists would be wise to examine and embrace the benefits of real collaboration. Finding more creative ways to reconcile dwindling financial and political support at the federal level with the growing economic and human demands of climate change will require new levels of partnership and cooperation among all three layers of the community leadership ecosystem.

Feature image via the Sankofa Community Redevelopment Foundation.