Looking for Signs: Zohran, Good Risks, and Sewer Socialism

In his victory speech, Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani referenced Mario Cuomo, the father of his twice-defeated opponent. “A great New Yorker once said that while you campaign in poetry, you govern in prose,” Zohran said to the cheering crowd. “If that must be true, let the prose we write still rhyme, and let us build a shining city for all.”

Much has been written about the poetry of Mamdani’s campaign: his retail politics, his message discipline, his mastery of vertical video. But since the election my mind has been drifting from poetry to prose. The municipal level is where the capacity of our governing institutions is most clear: you can see it in the buses that run or don’t, the housing that does or doesn’t get built, the coalitions that hold or fracture.

Taking Good Risks

My first political moment after moving to New York was voting for Zohran in the Democratic primary. My second was getting arrested.

A friend organizing with IfNotNow planned an action to voice opposition to the continued starvation of Gaza and arming of Israel. After a big rally at Columbus Circle, a smaller group would occupy the street in front of Trump Hotel and refuse to leave. The night before, one of the organizers explained to our group why she decided to risk arrest. “I’ve been wanting to put more on the line, something to show that Jews don’t support this,” she told us. “And good risks are hard to come by.”

The cops moved in while we were reciting Mourner’s Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. As they loaded us onto the buses headed to jail, I caught sight of Motaz Azaiza. The same photographer who documented Gaza under bombardment had turned the same camera lens on us, bearing witness to a group of Jews refusing complicity. The moment of inversion still sticks with me. So does the 6’3” Black cop wearing tzi-tzit under his NYPD uniform singing “Home on the Range” while he patted me down in central booking. Only in New York.

Sitting in the holding cell brought home the difference between casting a ballot and joining a movement. Solidarity is not an abstract principle, but a lived commitment. One of the things that united the group of Jews getting arrested was a belief that our safety was bound up with others. The AIPACs of the world actively make us less safe with their far-right alliances and investments. Their rejection of multiracial progressive movements on the litmus test of insufficient support for Israel emboldens authoritarianism abroad and closes the door to our best shot at combatting it here at home. Of course, no movement is a magic bullet. Working within a coalition means embracing the messy work of relying on others. But solidarity is a risk worth taking.

Signs and Sewers

Two weeks before the general election, I was on an Open House New York tour of the DOT Sign Terminal in Maspeth, Queens. The facility, where 70,000 brand new NYC street signs start their life every year, is part of the city’s largely invisible urban infrastructure. Shapes are cut and punched from big aluminum sheets. The Loading Zone–type signs that create the city’s maze of parking rules are “powdered”—painted and cured to make the metal weather resistant and nonreflective.

Surprisingly, many other signs are screen-printed. Red ink is pressed onto hexagons covered in white “high intensity prismatic,” leaving the outline of four perfectly spaced letters. This batch of STOPs will stay in the facility until it is time for them to join the fleet of 1 million signs across the five boroughs. The sign factory is one small piece of what makes New York work. But to explore whether socialist governance can maintain this type of infrastructure at scale, we have to look back a century.

In 1910, Milwaukee was a city in crisis. Rapid industrialization had brought waves of German and Polish immigrants to work in the breweries and tanneries, but the city’s infrastructure couldn’t keep up. Sewage ran directly into Lake Michigan, the source of the city’s drinking water. Typhoid outbreaks were common. The streetcar system was privately owned and notorious for overcrowding and accidents. Housing was scarce and expensive, and political corruption was endemic.

The Social Democratic Party, led by Emil Seidel and, later, Daniel Hoan, ran on a simple premise: make the city work. They weren’t preaching revolution; they were promising clean water, safe transportation, and an honest government. When Seidel became mayor in 1910, he immediately faced a hostile city council and a state legislature that stripped Milwaukee of home rule powers to prevent socialist reforms. But the socialists were patient and focused on municipal administration.

Hoan, who succeeded Seidel in 1916 and served for 24 years, perfected this approach. Under his tenure, Milwaukee built the first public housing project in America, a response to the housing crisis that didn’t require state approval. It established municipal ownership of the water and sewer systems, finally addressing the typhoid problem. It created the first municipal bus system, competing with the private streetcars until the city could buy them out. It built parks, libraries, and public markets. The city earned a reputation for efficiency and cleanliness: “the clean German city,” a phrase carrying its own complications of ethnic politics.

But sewer socialism wasn’t just about infrastructure; it was about rebuilding trust in institutions through making the delivery itself political. The socialists knew that every pothole fixed and sewer line installed was an argument for what government could do—the infrastructure was the ideology made concrete. They were relentlessly pragmatic, often frustrating more radical socialists who wanted faster transformation. Hoan’s governing philosophy was “socialism in one city”: prove it could work at the local level before asking people to buy into broader systemic change.

The coalition that sustained this—German and Polish immigrants, trade unionists, progressive middle-class reformers—was fragile and required constant tending. When the Red Scare swept the country after World War I, Milwaukee’s socialists were attacked as un-American despite their moderate reforms. When ethnic tensions rose during and after the war, the coalition strained. Hoan lost re-election in 1940 partly because the labor movement fractured between AFL and CIO unions, and partly because the Democratic Party had absorbed much of the socialist agenda under President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

The lesson wasn’t that sewer socialism failed, it was that even successful municipal socialism faces limits. State and federal governments can override local reforms. Economic forces beyond city control—depression, war, deindustrialization—can limit horizons. But coalitions built on tangible improvements are durable and can have effects far beyond their immediate material advancements, shaping the public’s imagination around what is possible. But durability isn’t guaranteed, as another New York coalition would soon learn.

Stress Testing the Coalition

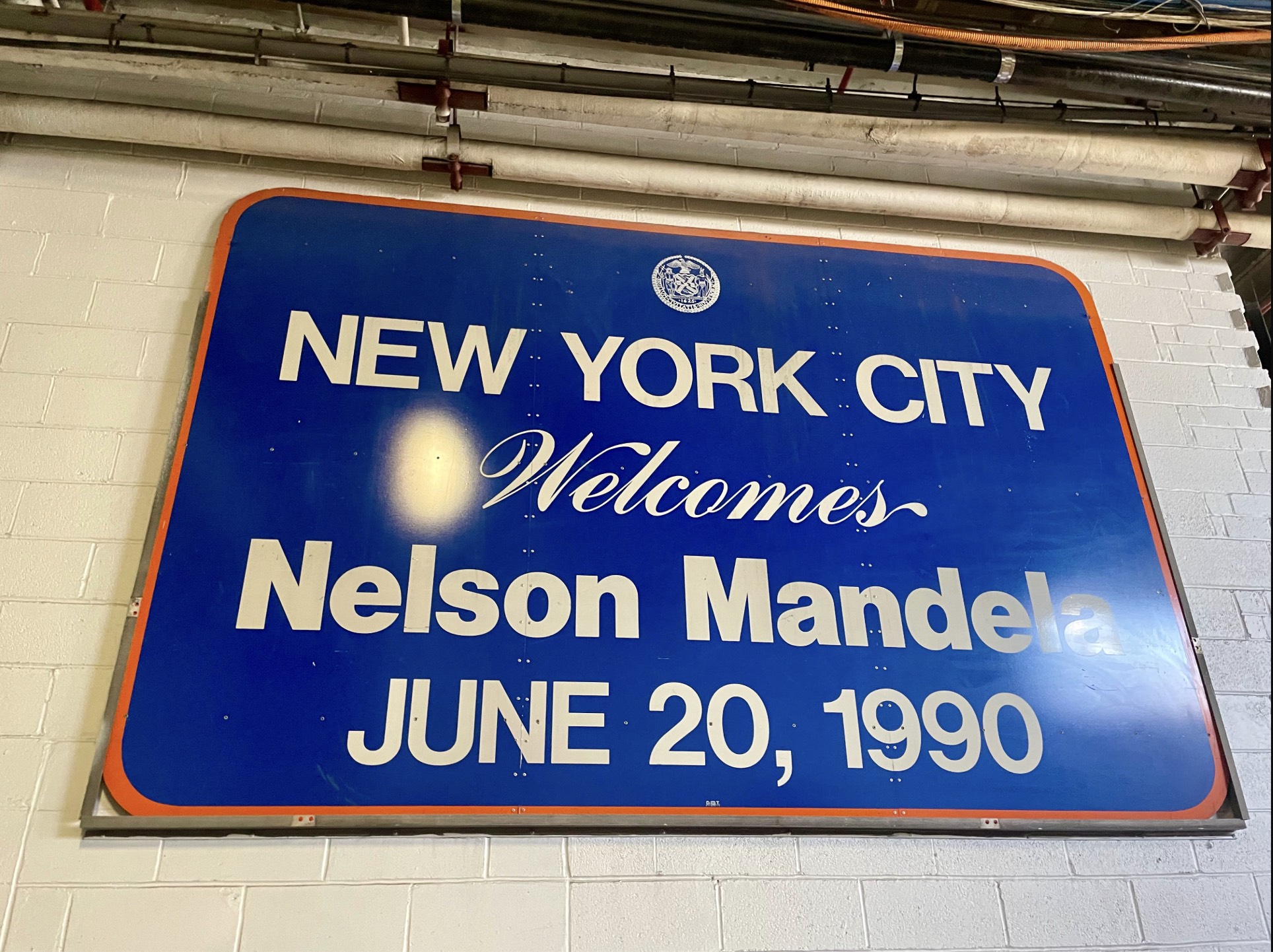

On the wall in the Maspeth DOT Terminal are signs from the past: New York Welcomes the Grammys!, New York Salutes the Troops of Desert Storm. And the final one before you turn the corner toward the screen-printing room: New York Welcomes Nelson Mandela. In 1990, the city’s first Black mayor, David Dinkins, celebrated Mandela with a ticker-tape parade after his release from prison. But some members of the Jewish community, upset by Mandela’s support for Palestine, threatened to protest, a fissure that would prove persistent. “Praising Mandela, Dinkins Threatens Fragile Coalition,” read the New York Times headline.

A year later, in Crown Heights (a few blocks from where I now live), a car in a Hasidic rabbi’s motorcade struck and killed a seven-year-old Black child, Gavin Cato. In the riots that followed, a Jewish student, Yankel Rosenbaum, was killed in retaliation. Dinkins took criticism from all sides for his handling of the crisis. The coalition that had elected him—Black voters, progressive Jews, labor unions, outer-borough moderates—fractured. He lost re-election to Rudy Giuliani by two percentage points.

But we’re not in 1990 anymore. Zohran’s moral clarity on Palestine is more aligned with the Democratic electorate than Cuomo’s Israel boosterism. Rather than being a liability, it was one of the main reasons why he won a crowded primary despite it being wielded against him. Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ), an institution that traces its roots to a Shabbat dinner welcoming Mandela in 1990, threw its full weight behind Zohran with an early primary co-endorsement of both him and Brad Lander. This new coalition is not fracturing over Palestine, but forming around it.

Zohran has made a bet that standing firm on principle—even when costly—can strengthen a coalition rather than fracture it. That young people who’ve watched the institutions of American Democracy crumble with little pushback from feckless Dems will show up for someone who chooses to fight. Zohran’s success as mayor will hinge more on running the sprawling systems that make New York work than the politics of the Middle East. But for the movement, moral clarity on this issue builds trust that transfers to others.

We notice when things break. When the train is late, when garbage piles up. But we forget what it takes to make things work in the first place. That’s the prose of governing: not speeches or vision, but the daily machinery of keeping a city running.

I think what Zohran meant when he talked about rhyming prose was that signs and sewers and buses can be an expression of values, not a retreat from them. That you don’t have to choose between moral clarity and municipal competence. That good risks, taken together, can become good policy.

I don’t know if the buses will be free in four years. I don’t know if Zohran can hold a coalition for 24 years like Hoan, or if it will fracture, as happened with Dinkins. But I do know the realm of the possible expands when people stay engaged: packing city council meetings, organizing tenant unions, knocking on doors. In a promising sign, activists just launched Our Time, a 501(c)(4) focused on sustained mobilization of the Mamdani coalition. Policy change isn’t inevitable; it is earned. The signs in Maspeth will keep getting made either way. The question is what they point toward.

For more writing from this author visit his Substack here. Featured image via The Guardian. All others by the author.