Some of a Good Thing: The Legacy of Frank Gehry

A friend of mine recently commented on the big void now in Los Angeles. I have received many such sentiments from my friends and former colleagues on the passing of Frank Gehry, but not one quite so simply stated. Without doubt, Gehry—through his work and media omnipresence—occupied a large space in the creative pantheon of Los Angeles and beyond, architecturally spawning generations of disciples and, as recently noted on this website by Doug Staker, creating a spirit of nonconformity in academia. Meanwhile, he staked out the high-water mark of the city’s cultural arrival on the global stage while also appearing as a character on The Simpsons. I can comprehend these sentiments but, now removed from L.A., I do not feel them. Living in the land of Camillo Sitte, I now see Gehry as that freestanding church in Sitte’s city of otherwise attached ones, an apostate. But I always had such suspicions.

An indication of greatness might be legacy, what is left behind for others to continue. In this respect, Gehry’s greatest legacy may not be his numerous buildings of note as much as the trajectories he charted in materials and methods. His aesthetic use of cheap industrial materials championed their acceptance to expand the material palette for architects, thereby providing the profession with increased modes of expression, and a creative desire to find the uncommon in the common. His introduction of aerospace technology in the form of CATIA to calculate, visualize, and construct complex forms helped chart a path out of orthogonal orthodoxy, liberating architects to realistically imagine beyond Euclidian geometry.

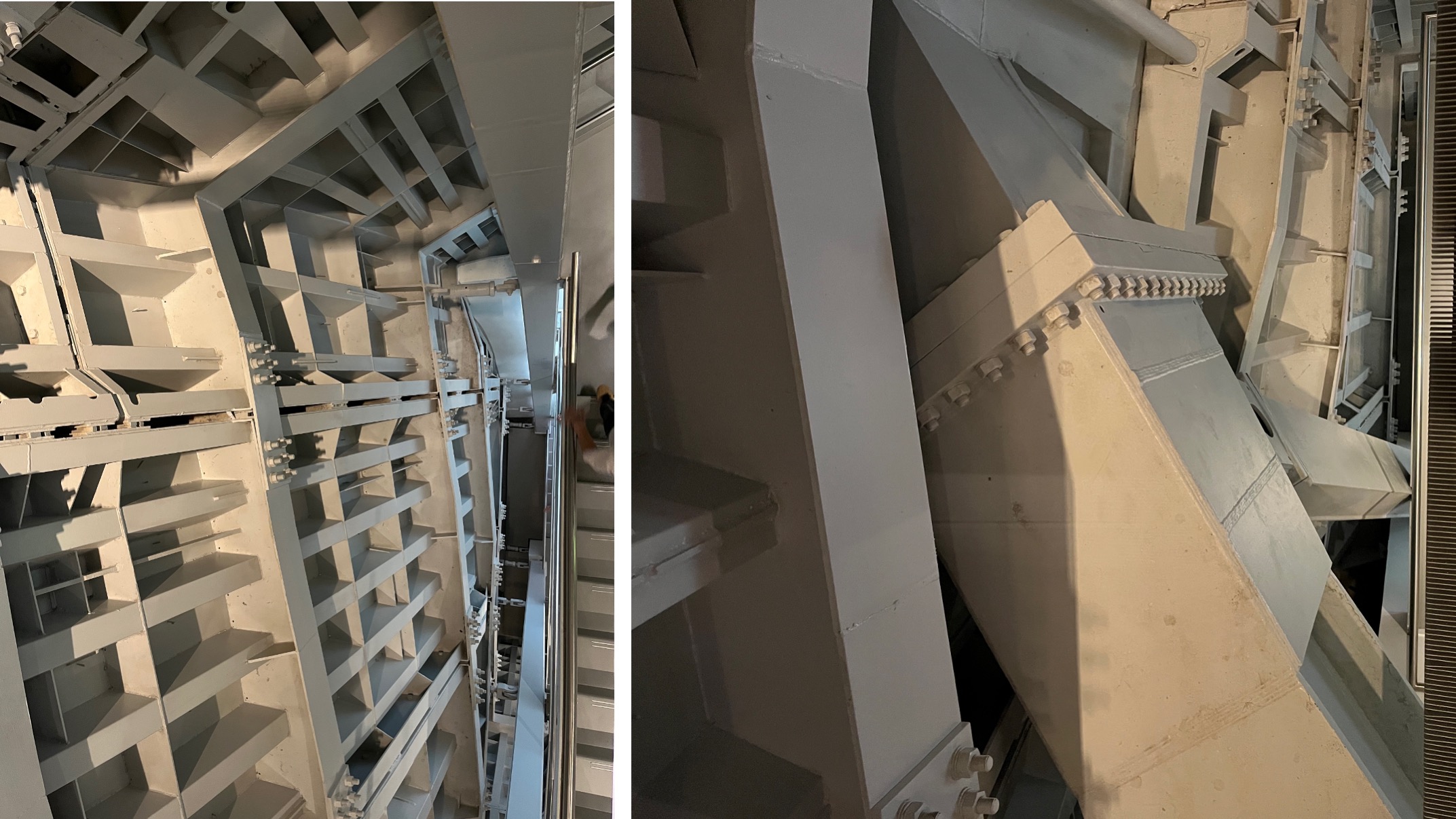

But as much as one can commend Gehry on these breakthroughs, one could also point to the waste inferred by them. In chain link and corrugated sheet metal lies a future of material disposability. Though impermanence is a characteristic of our modern consumer culture, in a time of environmental stresses, how responsible are these choices? The excess computational muscle of CATIA to construct Gehry’s extravagant forms brings into question the need for such forms, the need for the excess structural materials to realize them. One look behind the skin of the Louis Vuitton Foundation building sparks that inquisition. But waste has always been the byproduct of creative innovation. And many still marvel in experiencing the formal and spatial virtuosity of Gehry’s architecture. What’s the appropriate balance between innovation and waste? Perhaps a greater legacy of Gehry’s are these unanswered questions that he has left behind.

But maybe these shifting priorities are indications that Gehry is already an architect who should be seen as being of his time, a time when such environmental considerations were not foregrounded, when being a starchitect was. The completion of his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao in 1997 coincided with the rise of the internet, when the proliferation of imagery became ubiquitous, and the sculptural forms that would characterize his post-Bilbao work were ideally suited to the image-based world that we would inhabit. In Malcom Gladwell terms, he caught the wave at the right time, just like Michael Jordan caught sports celebrity at the right time when Nike was looking for a star. But that which giveth also taketh; the internet that helped create the starchitect class that Gehry would epitomize is now the source of its undoing. Timing is everything, as they say, and Gehry is of that time.

And despite his works’ global presence, he is also of a place, Los Angeles, which is why he has left such a big void there. Outwardly, it seems like only Los Angeles, with its identity driven by images and stars, could have produced a Frank Gehry, could have promoted and embraced him as one of their own.

His connection to the city has many times been outlined around his connection to the L.A. artists he befriended and socialized with, and from which he drew inspiration for his work. As has been well documented, the expressive freedom that these artists exhibited reflected the open spirit of L.A. in the 1970s and heavily influenced Gehry’s own groundbreaking addition to his Santa Monica house in 1978, indelibly tying him to the creative identity of the city, the city where anything goes, to the point that Gehry’s buildings and art are sometimes conflated. But that would be a mistake, as Gehry pointed out in a mid-1980s interview with Peter Arnell:

Arnell: But you are an artist, right?

Gehry: I’m an architect. I get that a lot because I’ve hung around with a lot of artists, and I’m very close to a lot of them. … So sometimes I get called an artist. Somebody’ll say,“Oh, well. Frank’s an artist.” I feel in a way that’s used like a dismissal. I want to say I’m an architect. My intention is to make architecture.

But what binds Gehry to Los Angeles lies beyond his ties to the art world there. (One of his frequent art collaborators and an artist whose sculpture most mirrors Gehry’s later work in scale, form, and space, Richard Serra, is, notably, not an L.A. artist. Neither is Claes Oldenburg, another noted Gehry collaborator.) And here we return to Gehry’s freestanding church as an apostate in Sitte’s city. For Los Angeles, in its neutrally gridded lots and network of dominions, forms the canvas for the proliferation of object buildings. As opposed to Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, Los Angeles is a city of architectures, an ideal tabula rasa with generally nice weather all year long, which liberated Gehry to ply his trade in creating qua-object buildings, to study what makes a building stand out further amid all the noise. But it was not always this way for him. As he stated in that same Arnell interview:

And there’s an even bigger picture in urban design and city planning—you know I studied city planning, not architecture, in graduate school … in the beginning the whole idea of doing houses for rich people was just abhorrent to me. I was more interested in this bigger thing which I saw as lying with urban design and large-scale projects. What I found out was that it just meant going to these meetings which only led to a lot of planning reports and a lot of grandiose dreams that never materialized. … It was too complicated. So you start back-pedaling to something that’s more realistic and end up doing smaller buildings, which you can do one at a time in our culture.

Though he admits backpedaling into making buildings, his Loyola Law School, built at the time of the interview, reflected his urban interests, as did his Edgemar Center of 1988 (which I was fortunate to work in for a few years). The houses he was doing at the time also indicated such interest; rooms were designed as separate objects, giving him the opportunity to compose them as village-like assemblies. But by the time his Vitra Design Museum was completed shortly thereafter, his objects had melded into a single larger one, maturing into the Guggenheim Bilbao, which indicated his design direction thereafter. With the resultant “Bilbao effect,” it seems that Gehry’s solution to urban design ever since has been simply to do more Frank Gehry buildings, a proliferation of his design style masquerading as solutions to depressed urban and institutional ills in far flung places. (The Simpsons got this right.) This belief that a building can be a substitute for urban design can only stem from working in a city that thinks zoning and planning regulations are urban design, putting the onus of making urban space on the back of a building—or, in urban design parlance, an object. Where urban space in Sitte’s city was once the product of intent through the shaping of form, it is now in the postwar American city of which Los Angeles is an apt representative, the consequence of objects missing. And in response to this L.A. condition and its culture of more, Gehry was intent on using more to ensure that his objects would not go missing. His is an architecture of unapologetic extremes.

So perhaps, in our skeptical times, we should feel fortunate to have so many Frank Gehry buildings. Sometimes, his potent imagery can make us forget how truly prolific a builder he was. Philip Johnson once said that what made the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe so great was that it was easy to copy. Immanuel Kant prophesied that truth was tested by its level of universality without contradiction. Gehry’s work is proof that Johnson was wrong (as he was with Mies, for his work is not easy to copy well). Like it or not, the power of Gehry’s work is its uniqueness, one that comes from authorship—his—and thus cannot be replicated. And due to this uniqueness, it could never be universal, and thus does not pass the Kant test. But little does, perhaps providing evidence that sometimes it’s better to not have too much of a good thing. Thanks to Frank Gehry, though, we have some.

Featured image: The Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, Spain. Photo by Benny Chan | FOTOWORKS.